![]()

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

JACKSON POLLOCK’S STUDIO FLOOR: A Brief History

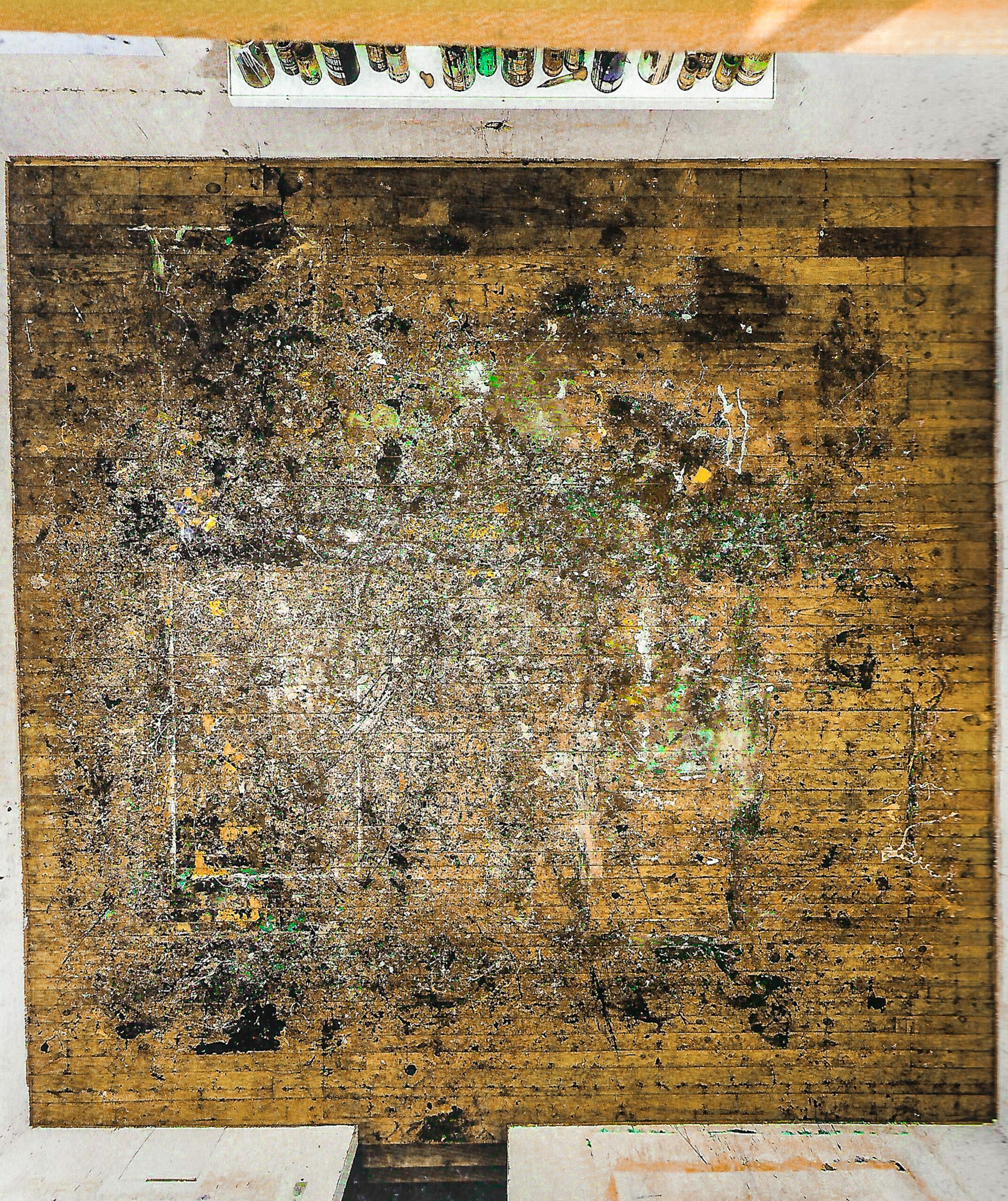

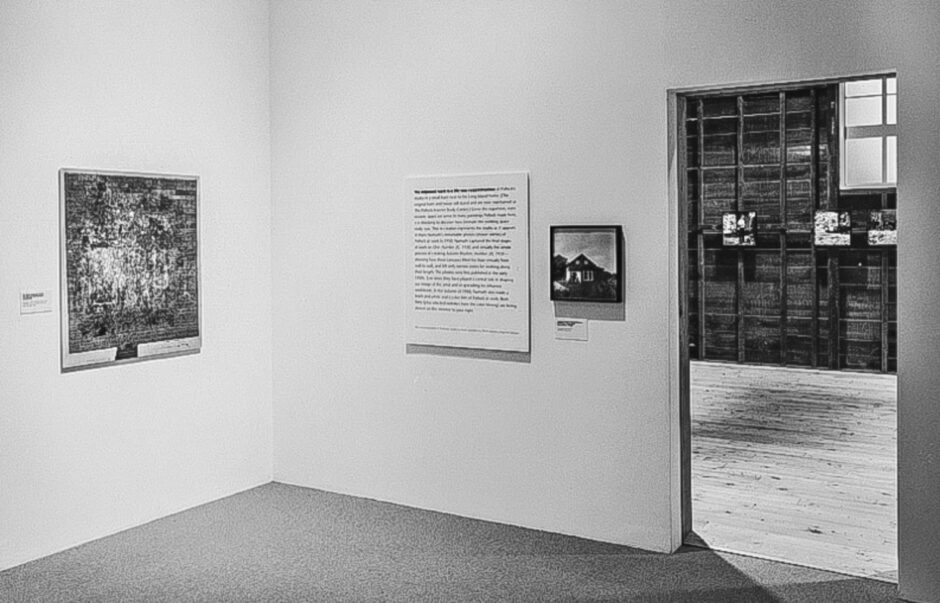

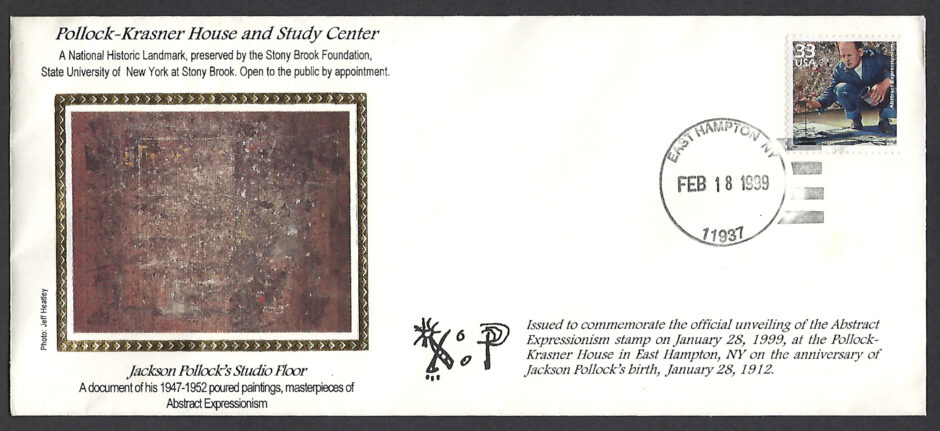

The extraordinary artifact that documents many of Pollock’s most famous paintings was revealed during the preparations for opening his former studio—which was used by Lee Krasner after her husband’s death in 1956—as part of a historic site interpreting the two artists’ lives and work. An exhibition of photographs and text panels in the building explains its evolution.

Built as a storage barn for fishing equipment, it stood behind the house, blocking the view of Accabonac Creek. Before converting it as his studio, in June 1946 Pollock had it moved to the north side of the property and had the original concrete floor replaced with wood. On that surface, Pollock refined his singular pouring technique, placing the canvas or other support on the floor and working around it from all four sides, using liquid paint applied with sticks, hardened brushes, and basting syringes. His energetic gestures often extended beyond the support’s edges, leaving colorful overflow from his spontaneous compositions.

Since the building had no electricity or heat, Pollock could not use it after dark or in cold weather. But in the early months of 1953, after a year of exceptionally strong sales, he had the studio renovated. The wood floor was covered with Masonite squares—leftover material from a printing job by his brother Sanford, a professional screen printer—which preserved the evidence of Pollock’s work on that surface. Insulation and Homasote wallboard were installed, and the interior was painted white. A kerosene stove and fluorescent lighting also went in, so he could use the studio year-round and at night.

Sadly, by 1953 Pollock was losing his struggle with alcoholism. His production began to decline, and he stopped painting in 1955. He died the following year in an automobile accident, after which Krasner began using the barn studio. Evidence of her dynamic action-painting technique is visible on the walls. Following her death in 1984, the property was deeded to the Stony Brook Foundation, a non-profit affiliate of Stony Brook University. In the process of converting the property as a public museum and study center, the Masonite covering was removed by conservators, exposing the residue of Pollock’s most innovative and productive years, 1946-52. In several cases, the marks on the floor can be correlated to specific paintings, especially Number 3, 1950, Convergence: Number 10, 1952, and Blue Poles: Number 11, 1952.

— Helen Harrison

———————————

See, also: AAQ / Article — Pollock: The Pollock-Krasner Studio / link

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

![]()

A team from New York Conservation Associates removed the Masonite boards,

used as flooring in the 1953 renovation of the Studio.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Archival Image of the Barn, 1950.

Archival Image of the Barn, 1950.

——————————

—————————————-

May, 2018

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Photographing Jackson Pollock’s Studio Floor

In 1998, I was asked by the Pollock-Krasner House to photograph the floor of Jackson Pollock’s studio for the upcoming Museum of Modern Art’s Jackson Pollock Retrospective. An assistant curator and I discussed different angle views or, possibly, section views, shot directly from above that could be merged to form an overview. Given the dimensions of the space – approximately 20’ x 20’ floor with a maximum ceiling height of 16’ – it was not known, nor easily determined, whether a view of the entire floor surface could be obtained from a point above the center of the floor. If so, an overview would require a 4×5 format for clarity. A working height of at least 12’ – and, practically, no greater than 14’ – would be required.

I spoke to a technician at Schneider Optics, who, after some calculation, was confident that its 47 mm Super-Angulon XL lens would provide the requisite coverage at 12’ above the center point. I arranged to have a sturdy metal frame made to support the weight of a 4×5 camera positioned at 90 degrees to the floor.

Two rafters were placed above the floor to support the metal frame & camera; two additional rafters were also placed half the distance to the walls on either side to support lights. The technician was right – the 47mm just covered the floor area at that height.

Corner to corner sharpness was, of course, a major concern – the film plane would have to be parallel to the floor plane. Adjustments to the metal frame were made with shims. I used the large type of four ‘Postal Express’ envelopes, placed on the floor of opposing walls, to help focus the camera. I used Polaroid negative film and a light box with magnifier to check the focus – a Polaroid proof would not show image sharpness as well as a negative.

Given the structure of the studio, photographing the studio floor would be like photographing a painting at the bottom of a box. I thought that four halogen lamps, clamped to the rafters, and aimed at opposite corners, would give even illumination. Once the lighting was in place, I took light meter readings at the corners, at midpoints of the walls near the floor, as well as at the center of the floor, making adjustments as I proceeded. I used new halogen bulbs in the hope that the color temperatures would be consistent (color temperature of halogen bulbs changes slightly with age). The 47mm lens required the use of a ‘center filter’ — attaching a filter to compensate for color variation would have been difficult under the circumstances. Because the processing lab was over seventy miles away, compounded by practical considerations, it would have been virtually impossible to arrange for a test of film emulsion, desirable when photographing artwork. I would have to do the entire shoot, requiring bracketed exposures, with no opportunity to make adjustments in lighting or exposures.

A twelve-foot ladder was carried back and forth across the floor for each exposure. I used Fuji 64 transparency film and Fuji NPL, a color negative film, both of which, with bracketing, required a total of twelve ladder transports – backing up each exposure with a second, following at least that number for the Polaroid exposures made before the actual film exposures.

I set the camera lens at f/22, and, standing just beyond the doorway into the studio with a bulb cable release, triggered the shutter for each exposure. It should also be noted that given the power requirements for the four halogen lamps, a generator had been set up outdoors for the two-hour shoot, from setting the lights to focusing with Polaroids to making the final exposures on film.

One final note – to see the entire floor, practically speaking, is only possible by looking at the photograph itself. To visit the site, stand in the doorway or walk across the floor, it is not possible to ‘see’ the entire surface. This was true as well for me, the photographer, because the ladder and rafters prevented me from seeing what the camera & film would record once the ladder & photographer had cleared the studio. So, the resultant 4×5 image was a revelation.

Helen Harrison, director the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, assisted me during the shoot.

—————————-

I used a 4×5 Linhof camera with a Schneider 47 mm Super Angulon XL lens. — Jeff Heatley.

—————————————-

A 4’ print was made and hung in time for the Jackson Pollock Retrospective at MoMA, and the photograph was included in the exhibit’s catalog, as well.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

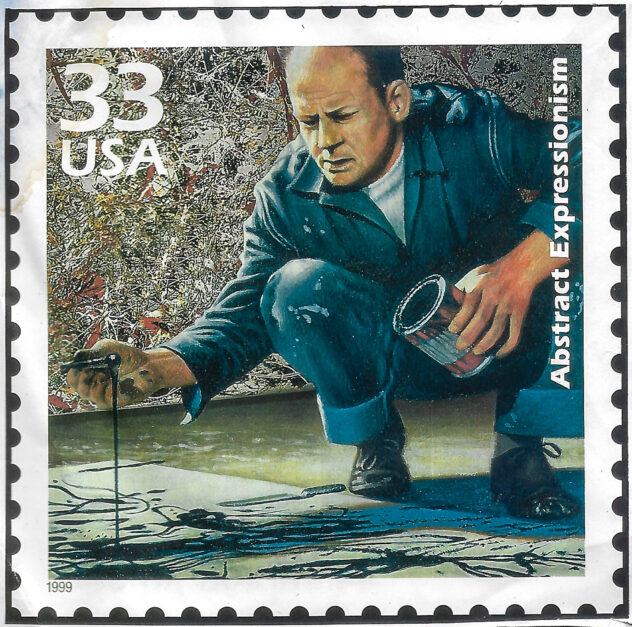

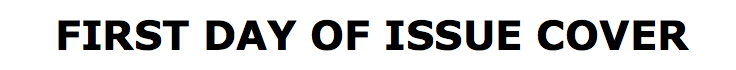

Commemorative Stamp / Celebrate the Century Series, image based on a b&w photo by Martha Holmes, Time/Life, colorized by Howard Koslow. Note that Pollock’s cigarette, as per original photo, was removed. Issued February 18, 1999. Copyright United States Postal Service. All rights reserved.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

————————————————-

Note: The glyph is a doodle by Pollock in one of his checkbooks

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Visit: Stony Brook University | Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center – link

Also, The Pollock-Krasner Studio by Helen Harrison – link

And, Pollock-Krasner Studio, Springs – link

And, Jackson Pollock, 1943 Mural at the Getty Center by Helen Harrison – link

And, Pollock: Architect Peter Blake’s 1949 Museum Design / Model – link

And, Photograph – Jackson Pollock’s Studio Floor, 1998 / Prints for Sale – link

————————————-

Pollock Floor photographs © Jeff Heatley.

An exclusive AAQ / East End Portfolio.

__________________________________________________