The Carriage Museum, with more than 200 carriages; Madison Square Fountain (NYC, ca. 1880)

for people & horses; and Samuel West’s Blacksmith Shop.

—————————————————–

A Smithsonian Affliliate

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Portfolio Sponsor: Riverhead Toyota

———————————————

——————————————————-

The largest and finest collection of horse-drawn vehicles

and related transportation artifacts in the country.

——————————————————-

GRACE DARLING. Concord Carriage Builders, Concord, NH.

Gift of St. Paul’s School, 1952. Carriage Museum lobby.

The “Grace Darling,” named after the maritime heroine who persuaded her father, the keeper of a coastal lighthouse, to rescue shipwrecked passengers, was used by the Huntress family who operated a livery service from the 1860s to 1904 in South Berwick, Maine. It is reputed to have delivered summer travelers to a steam packet, also named the Grace Darling. St. Paul’s School, Concord, New Hampshire, later used the vehicle for transporting athletic teams and students to other school outings. It is the largest vehicle in the collection, measuring eleven feet high, eight feet wide and twenty-three feet long.

____________________________________________

Going Places Gallery

America Gets Moving

Carriages – not cars – once ruled the road. These forerunners of automobiles and trucks were absolutely essential to American life in the 1800s. Carriages came in an amazing assortment of sizes, shapes and finishes. And they had a wide variety of uses. They moved people from place to place, transported goods, demonstrated their owners’ pride and accomplishments and provided new leisure opportunities. But carriages were not for everyone. Owning a vehicle, and the horse or horses to pull it, took a good deal of money. It might surprise you to know that a smaller percentage of the population then owned carriages than now own cars.

The standard of living of Americans improved greatly during the 1800s. As a result, more and more people were able to own vehicles and in turn were able to demand more and better roads. And as roads grew and improved, people could go more and more places and faster. This, in turn, greatly helped the developing American economy, since horse-drawn vehicles often provided the necessary connections between other forms of transportation – trains, canal boats and steamships – to get people and goods from point of origin to final destination.

A time line and a video, courtesy of the History Channel, place the “carriage story” into a broader context of American history, and a colorful interactive map of Long Island presents the changing transportation networks in which horse-drawn vehicles played so important a role. “People stories” complement the vehicles by introducing someone associated with each, including owners, drivers and craftsmen.

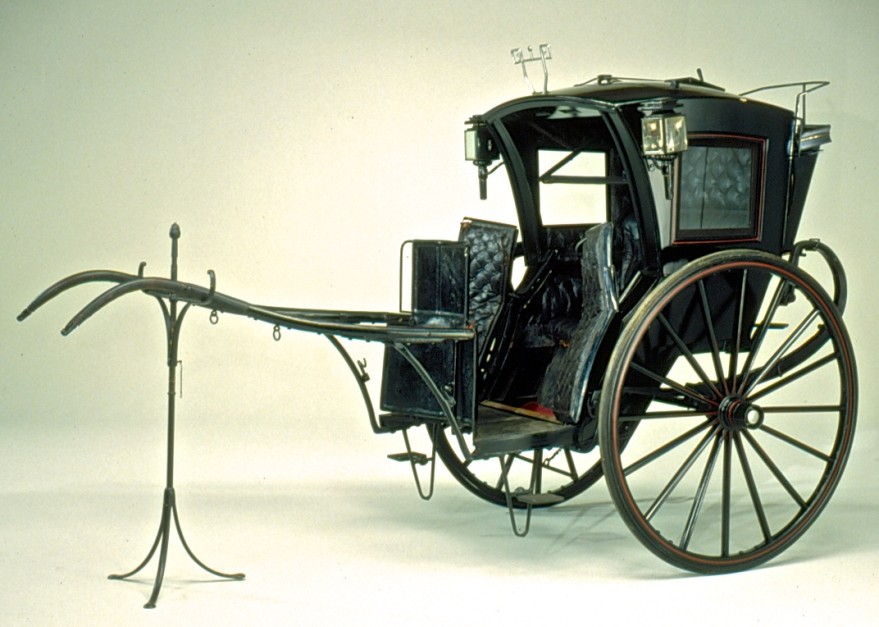

COUPE ROCKAWAY. A.S. Flandrau, New York, NY, 1871.

This vehicle type, known as the rockaway, originated on Long Island. It was named after the village of Rockaway, Queens, then a fashionable beach resort. Carriage shops in nearby Jamaica perfected its design. An enclosed family vehicle, the rockaway’s most distinguishing feature is its roof. The roof extends over the front seat to give protection from the weather to the driver.

CHARIOT D’ORSAY, 1875-1885. Million & Guiet, Paris, France

The chariot type of carriage was recognized by its elevation, large wheels, and extreme elegance. It was driven by a coachman and accompanied by footmen to assist passengers. This carriage, with its silver-plated hardware, belonged to William K. Vanderbilt, one of the wealthiest men in America.

MARKET WAGON, ca. 1900. Unknown American maker. Gift of Mrs. Henry Lewis III, G. Howland Meyer, S. Willets Meyer and Charles G. Meyer, Jr., 1950.

Market wagons carried produce from farms to urban markets and manufactured goods from factories to distant customers. Produce was typically stacked as high as possible and covered with a tarp secured by ropes. Sometimes the heavy-laden wagons were carried on flatbed railroad cars or aboard ferries. This wagon was owned by G. Howard Leavitt, a prosperous landowner in Bayside, Queens.

FOUR WHEEL SKELETON WAGON, 1855-1865.

Unknown American maker. Museum Purchase, 1953.

This wagon is typical of the extremely lightweight vehicles developed after 1850 for trotting races. The shape is related to heavier road wagons, yet in the skeleton wagon every element has been reduced to only what is absolutely necessary.

WELLS FARGO COACH. Abbot, Downing & Co., Concord, NH.

Gift of the Railway Express Agency, 1951.

The overland express coaches of Wells, Fargo & Company were critical to the westward expansion of the United States. During the mining boom, these coaches transported millions of dollars worth of raw gold bullion to exchange offices, as well as mail and passengers. When Wells Fargo announced overland passenger service in April 1867, customers could travel from Sacramento to Omaha for $ 275. This coach could hold nine passengers in the interior and six to ten on top.

______________________________________________

A Carriage Exposition

Selling Carriages to a New America

This gallery is inspired by the display of carriages at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. From oil lamps to Edison’s electric lights…from farm buggies to Ford’s Model T…nearly everywhere you looked, the United States underwent profound changes between 1865 and 1918.

In 1865, family farms were the country’s economic heart; by 1918, factories had become the nation’s driving economic force. Rapid industrialization and technological change turned out more goods using less labor at lower prices. The resulting new products were marketed through glossy advertising and displays to eager crowds of consumers at fairs, expositions and markets.

The most spectacular display of all was the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 attended by more than 30 million visitors. Here, along the shores of Lake Michigan, where people saw cultural and technological treasures, they could also see the newest and best in the world of carriages. Carriage entrepreneurs used the fair for the same purposes as other industries – to promote their wares and to sell, sell, sell.

Calèche, ca. 1880. Million, Guiet & Company, Paris, France .

The French term calèche refers to the folding, collapsible hood found on certain types of horse-drawn carriages.

A highly fashionable mode of transportation during the nineteenth century, the calèche was intended for town use, park outings, and formal social visits. Designed for warm weather, the open-air carriage afforded its passengers the opportunity to see and to be seen while out and about. Wealthy railroad tycoon William K. Vanderbilt originally owned this carriage and likely used it while traveling to and from his large Oakdale, Long Island, estate “Idle Hour.”

In the early 1960s, inspired by this sublimely chic carriage, the world-renowned Paris fashion house Hermès introduced Calèche perfume. Press releases promoting the new scent explained “that this most elegant, modern perfume was named after a most elegant carriage of the nineteenth century” and described the perfume as “a remarkably beautiful fragrance, neither heavy or outdoorsy … it is sophisticated and haunting, all pleasing, all-woman.” Today, Calèche perfume remains one of most popular Hermès products and still features the image of this stylish vehicle.

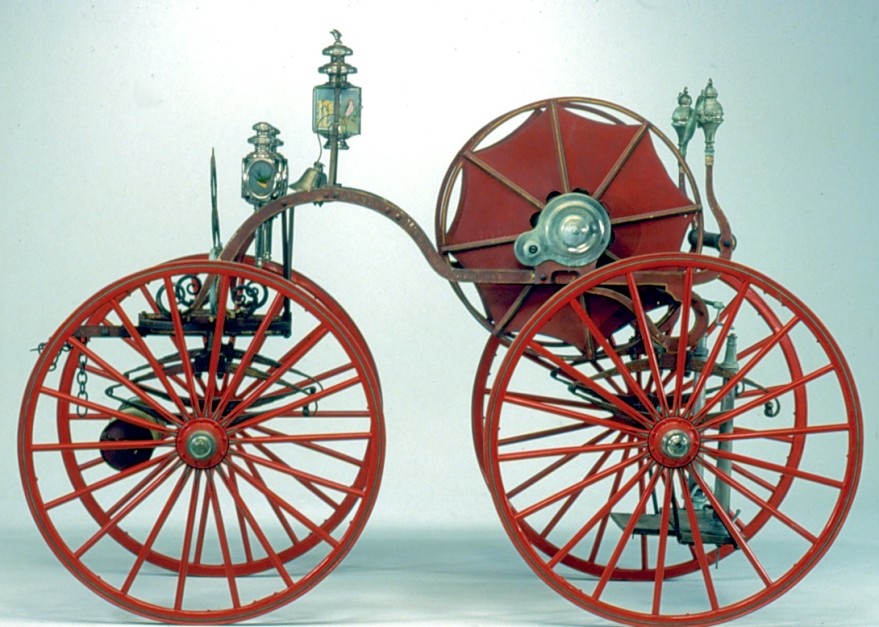

PARADE HOSE CARRIAGE, 1870-1880. Rumsey Mfg. Co., Seneca Falls, NY.

This carriage, originally owned by Ringgold Hose Company #1, had silver plating from its axles to the statue of Cupid on top and mirrored on the ends of the hose reel. It was used by the Ringgold Hose Company in parades for over 70 years.

_____________________________________________________________

Making Carriages:

From Hometown Shop to Factory

The Studebaker Company, South Bend, Indiana

Carriage production changed drastically during the 19th century. At its start, the manufacturing of carriages occurred almost exclusively in small shops staffed by skilled craftsmen. By century’s end however, large mechanized factories had all but replaced small carriage shops.

The Studebaker Company serves as an excellent example of the changing economic landscape.

In 1852, with just $ 68 and the craftsman skills taught to them by their father, Henry and Clement Studebaker established a small wagon shop in South Bend, Indiana. Soon business boomed. By the start of the Civil War in 1861, the Studebakers had sufficiently expanded production and gained a reputation for quality to be granted U.S. government contracts for the production of war-related supply wagons, gun carriages and ambulances. During the remainder of the 19th century, the company continued to grow with Studebaker dealers and distributors popping up throughout the United States and in several foreign countries.

Studebaker was among the first carriage companies to experiment with the “horseless carriage.” The company first produced a series of electric automobiles started in 1902 and in 1904 switched to the production of gasoline powered vehicles. While Studebaker still manufactured wagons and carriages, their appeal gradually waned. In 1911, for example, the company’s gross sale for automobiles was more than triple that of their total sales of wagons and carriages.

TWO-SEAT PLEASURE WAGON, 1895-1905. Studebaker Brothers. Gift of Ward Melville.

The pleasure wagon, a square-bodied, four wheel passenger vehicle was widely used in New England in the nineteenth century. These were often made with removable seats so that the inner space could be used for goods and luggage. This wagon is painted “Brewster Green” and black, a popular color scheme for early automobiles as well as carriages.

The Graves Carriage Shop, Williamsburg, Massachusetts

Small-town carriage manufacturers once dotted the American landscape. But as automobiles replaced carriages, these became outmoded. So they were typically disassembled and their obsolete contents carted off to junkyards.

The Graves Carriage Shop, reinstalled in part here, is a remarkable exception. The Graves family began making carriages in the mid-nineteenth century, when Norman Graves, a farmer, started to build and repair horse-drawn vehicles as a sideline. In the 1870s, he built a mechanized shop in the center of Williamsburg, Massachusetts, where he and others who worked with him manufactured buggies, farm equipment, market wagons and sleighs.

Norman Graves’ descendants continued the enterprise. In addition to building new carriages, they repaired, repainted and reupholstered old vehicles. And they often took trade-ins as partial payment for newer vehicles – just as car dealers do today. The Graves shop remained one of the chief businesses in a small town until the 1920s, when the family opened a separate automobile dealership next door, in effect joining the competition. The carriage shop was then locked up for more than 75 years, kept by the family for its historical and sentimental value. In 2003, its contents were donated to the Long Island Museum by Ralph Richards Graves and Nicole B. Graves, in memory of Norman F. Graves.

________________________________________________________________

The Streets of New York

In the late 1800s, horses and carriages ruled America’s city streets…and what a scene it was! From sunup to sundown, cities buzzed like beehives. In New York, big horse-drawn omnibuses (the city buses of their day) and hacks (cabs) rumbled over Broadway. Yelling vendors, bellowing stagecoach drivers and thundering wagon wheels on cobblestones formed the urban soundtrack. Crossing the street was an even bigger adventure than it is now: amidst the jostling vehicles, New Yorkers had to step around dung heaps from the city’s working horses.

Carriages were everywhere in the city and used for many purposes. Delivery wagons contained fresh groceries, newly-cut lumber, supplies of every description. Elegant private coaches moved gracefully down Fifth Avenue, carrying rich residents to the office, the opera or a fancy meal. Heavy steam pumpers put out countless raging fires in the city’s tenements. And many immigrant workers relied on simple two-wheel cars, moved by their own muscle.

New York was also at the center of the carriage-making industry. In 1859, there were over 40 carriage manufacturers in the city, selling nearly 5,000 vehicles per year. Those numbers continued to rise over the next decades. By 1880, Manhattan and Brooklyn together had 249 carriage makers. Even after the rise of motorized streetcars, the subway, and automobiles in New York, carriages continued to play an important – if ever-diminishing – role. Into the 1940s, horse-drawn vehicles still delivered milk, ice, and other basic items in spots where early trucks had trouble maneuvering. But the days of a busy, noisy, and endless procession of horse-drawn carriages were long gone.

CIRCULAR FRONT COUPÉ, ca.1860. Brewster & Company, New York. Gift of Ward Melville.

Literally a coach “cut” in half, the coupé is a small carriage designed for only two passengers. However, a small hinged seat is hidden behind the wall covering to accommodate an extra person if necessary. The interior is very elegant, with diamond-pleated burgundy satin, a mirrored vanity drawer, and a calling-card case with rich russet leather.

CONCORD COACH, 1866. Abbot-Downing Company, Concord, New Hampshire. Gift of Webster Knight II.

This nine-passenger coach was meant for long distances and heavy loads. Although the ride was undoubtedly rough, the coach is quite elegant inside: it is trimmed in red velvet and decorated with lace and damask curtains. The coach’s exterior was most likely painted by noted carriage painter John Burgham. One door features a peaceful seascape, but the other is decorated with a scene of an Indian attack, no doubt from the artist’s imagination.

Charles E. Fuller, proprietor of the Mattapoisett stage line in New Bedford, Massachusetts, had this coach repainted in about 1880 and drove it through the 1890s. The Concord Coach was the model for the stagecoach celebrated in literature and in so many television and film westerns.

GYPSY WAGON, ca.1860. United States.

Gypsy wagons (also sometimes called wardos) were found in Romani encampments on the outskirts of urban areas in the United States after the Civil War. Often highly colorful and built for comfort, they were used for traveling, fortune-telling, and mobile residences. This wardo’s body panels feature landscapes, seascapes, floral scenes, hunting scenes, a gypsy camp and horses. The front panels fold for access or closure to the interior.

This wardo belonged to Phoebe Stanley (sometimes referred to as “Gypsy Queen Phoebe”), from West Natick, Massachusetts. Her family belonged to the Romanichal (Romani people from the British Isles), and emigrated to New England in the 1850s. Phoebe married Thomas Stanley, a horse-trader by profession, whose family came to the United States from Liverpool, England, in 1857.

GYPSY WAGON Interior.

HACK PASSENGER WAGON, ca.1870. Abbot-Downing Company, Concord, New Hampshire.

A small stagecoach, the hack passenger wagon seats only four and was pulled by a pair of horses. The body is suspended on three-inch thick leather straps called thoroughbraces, which allow it to hang above the wheels and absorb bumps by swinging gently. This sturdy vehicle was used to deliver passengers, luggage and mail.

Joel Chase Piece drove this coach six days a week in Maine in the 1880s and 90s, starting at 4:30 each morning to deliver mail, small freight and passengers, picking up and delivering all along the route. As soon as they were old enough, each of his five sons learned to drive the route to make sure service was never interrupted.

HANSOM CAB,1885-1895. Forder and Co., London. Gift of Ward Melville.

A cab for hire, the hansom was named for a British architect who patented its design in 1834. The driver sits above the rear wheels, enabling him to see clearly and to maneuver the cab through tight spaces. The driver can open and close the doors from his perch. Hansom cabs were used on the streets of New York, as well as other cities. Its slim design made it perfect for driving through urban crowds and narrow spaces. A small window in the roof allowed the passenger to tell the driver his destination and to hand him the fare.

HOSE CART, 1870. United States. Gift of Association of Exempt Firemen, Patchogue.

Most 19th century municipalities did not have fire hydrants and needed to get water from a pond or stream. This was no problem if the fire happened to be near a body of water, but if not, a hose was connected from the water source to the pumper. Hose carts efficiently accomplished this purpose, unreeling long lengths of hose very quickly.

This hose cart was manufactured for Long Island’s Patchogue Fire Department and was used until 1904. It could carry 900 feet of hose and was pulled by the firemen themselves rather than by horses. Four-wheel hose carriages like this were known as “spiders”; two-wheel hose carriages were called “jumpers.”

POPCORN WAGON, 1907. C. Cretors & Company, Chicago.

Salt and butter filled the air wherever this vehicle parked to sell its hot, tasty treats. Popcorn was a brand new snack food when Cretors introduced their wagons at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, in 1893. The vehicle features a roll-down canvas canopy, handy for either hot summer days or a sudden July cloudburst. While waiting for their popcorn, kids watched “the Tosty Rosty” man – the smiling stuffed clown and company trademark, you can see perched just above the motor. As the motor ran, the clown came to life, cranking a small glass cylinder of peanuts.

STEAM PUMPER, 1873. Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, Manchester, New Hampshire.

Although steam pumper technology was available in the United States by 1839, it took a while for it to catch on. Volunteer departments believed that man was better than machine and that the new pumpers might impede on their work. This eventually changed in many cities, including New York, which organized its first fully functional, professional fire department in 1865, and began using steam pumpers shortly thereafter.

This steam pumper was built in 1873 for the New Orleans Fire Company. But weighing in at over 9,000 pounds and standing 10 feet tall, the engine was useless among the narrow and winding streets of the city. The engine was then transported back to the Amoskeag factory in New Hampshire where it was used to protect the factory and the city of Manchester from fires.

EASTERN ESTATE TEA COMPANY WAGON, ca.1905. Biehle Wagon Company, Reading, Pennsylvania.

Like moving billboards, wagon sides were the great advertising tools of their day. Businessmen took inspiration from elaborate trade signs, using a variety of paint techniques, colors, and trademarks to promote their companies for consumer’s eyes. Eastern Estate Tea Company’s lush red and yellow Pagoda logo – capitalizing the public’s fascination with the Orient – was seen in dozens of cities across New York State by 1910, at the height of the business’s success. This vehicle carried many goods, including tea, cocoa and spices, rice, maple syrup, peanut butter, and soap. Eastern Estate Tea Company was started by William Aitken, who expanded his business from a small shop in Pennsylvania to a large, multi-city enterprise headquartered in Manhattan.

_____________________________________________________

Driving for Sport and Pleasure

Racing at breakneck speed around a curved dirt track…parading in well-appointed splendor through a big city park…sleighing through the snow and ice on a crisp winter’s day – vehicles for sport and pleasure provided escapes into life’s most enjoyable diversions. The vehicles seen here include winter sleighs, pleasure wagons, and other carriages made for carrying well-to-do passengers to fun-filled destinations like resorts and country picnics.

Vehicles for sport and pleasure looked and functioned differently from work vehicles. They were often used in places removed from the city, especially in parks, estates, and on country roads. When Central Park opened in 1858, New York City explicitly prohibited omnibuses and express wagons from entering the park, as well as “any cart, dray, wagon, truck, or other vehicle carrying goods”; only non-work-related carriages were permitted.

In the 1800s, carriage makers designed and made pleasure vehicles that were faster and more comfortable, even on rough and uneven roads. Innovations to wheels, suspensions, shock absorption and interior comfort all improved the ride.

Owner-driven pleasure vehicles showcased the skills and mastery of their drivers, an abililty to handle both the horse and vehicle that earned them an honored status as a “whip.” Whether driving a carriage harnessed to a single horse, a pair, a tandem, or four-in-hand, the “whip” needed to be able to manage all sorts of challenges. High status was also achieved through a fashionable “turnout”: the suitable standard and properly-dressed drivers, grooms, passengers, and horses, as well as the properly chosen harnesses, fittings and other accessories for specific pleasure vehicles.

CRAWFORD HOUSE COACH, 1867. Abbott-Downing Company, Concord, New Hampshire.

Coaches such as this were often packed to capacity, with as many as 20 people and their luggage seated inside and perched on top. Leather straps under the vehicle, called thoroughbraces, an early shock absorber system, enabled the weighted-down vehicle to sway with the terrain and to ease the rough ride.

TALLY HO, 1875. Holland & Holland Builders, London, Great Britain.

Gift of the Museum of the City of New York.

This is the most historically important vehicle in the museum’s entire collection. Internationally famous, the Tally-Ho Road Coach was a catalyst of the road coaching movement in America, which hit its stride in the 1880s. The vehicle was brought to this country by Col. Delancey Kane, a founder of the New York Coaching Club and the main force behind the popularization of American road coaching.

Written about widely in newspapers and prominent publications of the time, road coaching became a major event, engaged in by upper class society figures and watched by nearly everyone. Road coaching took hold at a time that many Americans were feeling nostalgic for a seemingly simpler time in transportation, before stage coaches were supplanted by railroad travel. As Harper’s Weekly put it, “genuine, healthful enjoyment can be derived from one ride out of Pelham Bridge and back on the top of Colonel Kane’s coach than from the whole flying railway trip from New York to San Francisco.”

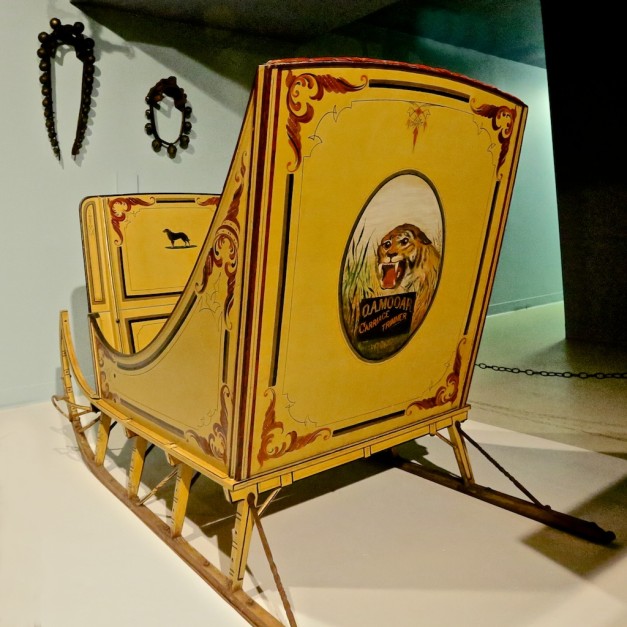

SLEIGH, 1830. United States.

Similar to larger trade vehicles, sleighs could become moving advertisements. Built decades before the Civil War, this sleigh was lavishly repainted for O.A. Moor, a carriage trimmer from Farmington Falls, Maine, in about 1875. It is decorated with scroll work, vivid striping and an ornately painted tiger. The painter of the sleigh, Lemuel Hodgkins, signed it beneath the oval painting of the tiger. Hodgkins worked for his father’s carriage-making business, and later became a school teacher and a real estate salesman in Aroostook County, Maine.

TRAP, ca.1890. Troy Carriage Works, Troy, New York. Gift of Katherine Thayer Hobson.

Traps were country pleasure driving vehicles that were sometimes used for hunting. A small compartment in the back of the vehicle was sometimes used to house a dog, and the early traps would later become the more elaborate dog carts in America. Traps could accommodate two to four passengers and were very easy to handle. Traps often featured a rear seat that could be removed or shifted for passengers to be able to ride backwards or forwards. This vehicle was used by a family in Washington County, New York.

___________________________________________

A Trip to Yesterday

Long Island in the Carriage Era

In this exhibition, you begin your trip to the lost Long Island of a century ago through a re-creation of the old Stony Brook Station and see the actual Depot Wagon in which turn-of-the-century guests were transported from the Station to Stony Brook and other local villages.

The Village itself consists of two-thirds-scale structures based on local buildings, circa 1900: the Old Stony Brook Post Office, the E. E. Topping Store (Stony Brook), and the Samuel West Blacksmith Shop (Setauket), in addition to the Train Station.

______________________________________________________

Gentleman’s Coach House Gallery

Fashionable Homes for Carriages

With their beautiful façades and handsome hardwood interiors, coach houses provided stately comfort for carriages and horses…but not necessarily for the people who worked – and sometimes also lived – within.

At a time when the wealthiest 1% owned more than 50% of the nation’s personal property (including many of the largest, most opulent estates on Long Island’s Gold Coast), carriage houses were the ultimate Gilded Age status symbols. “The seeds of social ambition,” wrote author and editor James Garland in 1899, “are first sown in the stable.” At its best, the private coach house projected an ordered formality that left nothing to chance, with ample ventilation, light and drainage to protect the expensive contents.

But those grand structures did not run themselves. They depended on a huge corps of servants, from the lowest paid and least experienced stable boys to highly skilled older head grooms. Despite coach house’ splendid outer appearance, the work inside was smelly, noisy, and intense at early and late hours – all reasons why these structures sat a good distance away from the main house.

By the end of World War I, many estate owners were leaving their grand coach houses behind for new automobile garages, and their coachmen were becoming chauffeurs. The carriages were increasingly relegated to storage and gathering dust.

ROAD COACH, ca. 1920. Peters and Sons, England. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Wilshire.

Despite the arrival of the railroad and later the automobile, some members of the gentry in Great Britain and their counterparts in the United States clung nostalgically to the world of road coaching and four-in-hand driving.

This vehicle, reputedly the last road coach made in London, bears the phrase “Olden Time” on its rear panel. It is equipped with mahogany wine-glass racks and a wicker basket for umbrellas. The makers, Peters and Sons, were leading English coach makers until their dissolution around 1930. One of the firm’s clients was the British royal household.

______________________________________________________

European Vehicles Gallery

From parlors decorated with Old Master paintings to coach houses resembling castles, America’s Gilded Age elites craved European cultural refinements. Indeed, most styles of American luxury vehicles had their origins in the Old World – landaus, caléches, broughams, and chariots d’ Orsay, to name a few. Ornate interiors, elaborate paint schemes, and even coats-of-arms seen on the panels of European coaches were adapted by Americans, in order to associate their vehicles with old money, blue blood and good taste. In 1878, New York carriage maker Ezra Stratton wrote that the super-rich were “aping the European fashion, now driving through our streets in the most approved style.”

But imitation stopped short of duplication. Traveling overseas, America’s wealthiest marveled at the startlingly different carriages they saw in London’s Hyde Park and along the Champs-Élysées in Paris. While their basic constructions were similar, European luxury vehicles, such as these, were heavier and featured more ornate ornamentation – more extensive use of gilding, more elaborate paint schemes, and more references to allegorical and classical figures.

Most of the European vehicles seen in this gallery were used by aristocrats or high officials on streets and promenades near their palaces and other halls of power. Four of the carriages were owned by Prince Adalbert of Bavaria (1828-1875), used in his lifetime at Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. After his death, they sat on the palace grounds gathering dust through two World Wars and did not arrive in the United States until 1959, when Dieter Holterbosch, a German executive with family ties to the Bavarian royals, purchased and displayed them at his Long Island estate at Belle Terre. He contributed them to this museum in 1966.

BERLIN COACH, ca. 1775-1785. Unknown maker, France.

The design of the Berlin coach, of Prussian origin, represented a major innovation in carriage construction. The body of the vehicle was hung from leather straps or thorough braces, creating a smoother and more comfortable ride. This feature also made the vehicle more maneuverable than its fixed suspension predecessors. This technology would be used later in other European and American horse-drawn vehicles, before the advent of springs.

This coach was sent from France to Rome in 1785, where it was used by Cardinal Pianetti, Pro-Governor of Rome under Pope Pius IX. Much later, Colonial Williamsburg used it in its film The Making of a Patriot.

***********************************************

PRAIRIE WAGON

Children’s Vehicles

Vehicles designed for children’s pleasure, pulled by people, ponies, goats, or dogs, were miniature versions of vehicles used by adults for both work and pleasure. They were made my major carriage manufacturers, as well as by firms specializing in children’s carriages, sleighs and sleds. These miniature vehicles were toys, but they also offered children the practical experience of handling reins, and sometimes the pleasure of driving.

—————————————————————

THE CARRIAGE COLLECTION

The extraordinary collection of horse-drawn vehicles at The Museums of Stony Brook [now the Long Island Museum] was begun by Ward Melville, a man fascinated by the past and committed to public education. He began in the early 1940s to collect the works of Stony Brook’s nineteenth-century artist William Sydney Mount; by the mid-1940s, he was collecting carriages. Mr. Melville’s interest in collecting paintings and artifacts related to America’s past was part of a trend of interest in American history and artifacts that began in the late nineteenth century and developed rapidly in the twentieth century.

Mr. Melville collected Mount’s paintings and drawings, as well as objects that had belonged to Mount and his family. Assisting Mr. Melville in his art collecting was Richard McCandless Gipson, whose connoisseurship and talent for patient negotiation significantly contributed to the development of Mr. Melville’s superb collection.

Mr. Gipson suggested to Mr. Melville that he might be interested in collecting carriages, observing in a letter to Mr. Melville, “Fine carriages in good condition are becoming increasingly rare. We know how automobiles have driven them off the streets, and leaky barns and neglect have relegated all to many to extinction.” By 1949, Mr. Gipson could write to Mr. Melville, “Again I say that your collection is fast becoming the most important in the country.”

Early in the formation of the collection, the guiding principle was to have the best examples of various types of vehicles, and the growth of the collection included the practice of upgrading by obtaining a better example of a type of vehicle already in the collection and disposing of the lesser example. From the beginning of this new collecting venture, Mr. Melville aimed to make the carriage collection “thoroughly representative of various types of carriages.”

As with his art collection, Mr. Melville always planned to exhibit his carriage collection to the public. The growing collection was stored in the late 1940s in barns at Richard Gipson’s residence in Old Field, and was exhibited to the public there on one occasion–on September 10, 1950, during a tour of historic sites that was sponsored by the Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities. In the same year, working with architect Richard Haviland Smythe, he began plans for converting the deteriorating Stony Brook Hotel building for housing and displaying the carriage collection.

On Saturday, July 6, 1951, the new carriage museum opened with a day-long festival to celebrate the occasion. Eighty of the 125 vehicles in the collection were exhibited in the new facility. The collection included not only horse-drawn vehicles, but accoutrements, such as harness, and a library of carriage-related volumes, pamphlets and prints.

Following the 1951 opening of the carriage museum, the collection continued to grow both by purchase and by gift. As private stables were demolished and their contents dispersed, and some museums with vehicles in their collections decided they could no longer house them, additional gifts were made to the new carriage museum.

In 1956, Mr. Gipson wrote to Mr. Melville: “Before 1953, we had been building the basic collection. Since that time, I have been endeavoring to perfect the collection and to search the country exhaustively for rare and early vehicles. Your collection now numbers many rare vehicles and holds its position as the finest and most comprehensive collection in the country….Each vehicle or each group of vehicles has been acquired with a definite purpose, for at all times I have had a well-defined goal of the comprehensive collection before me.”

As the collection’s reputation spread, many requests for information were received by the museum. A list of these correspondents was kept, and in 1960 Mr. Melville invited them to come to the museum to see the collection. The meeting resulted in the founding of the Carriage Association of America*, now an international organization of more than 3,000 members.

— The Carriage Collection, copyright 1986, The Museums of Stony Brook [now the Long Island Museum]. Abridged version.

*CARRIAGE ASSOCIATION OF AMERIA (CAA): www.caaonline.com

—————————————————————————————–

THE LONG ISLAND MUSEUM

1200 Route 25A, Stony Brook, New York 11790

631.751.0066

www.longislandmuseum.org

Hours of operation: Thursday through Saturday, 10 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sunday, noon – 5 p.m. Closed Christmas Day, New Year’s Day, Easter and select holidays on a case-by-case basis.

Long Island Museum Events: www.longislandmuseum.org/calendar.asp.

—————————————

Content provided courtesy of the Long Island Museum.

Special thanks to the Long Island Museum and Staff for assistance in preparing this Portfolio Album.

Visit: AAQ Bulletin / Of Note: Long Island Museum Celebrates its 75th Anniversary in 2014

Visit: AAQ Portfolio / Art: William Sydney Mount, American Genre-Painter.

Visit: AAQ Bulletin / Exhibits: Long Island Museum — Jackson Pollock Prints Exhibit.

————————–

——————————————

__________________________________________________

PORTFOLIO SPONSOR

===========================================================

AAQ Resource / Transportation: Riverhead Toyota

________________________________________________________________