Home Sweet Home with Henry Mulford, c. 1880., archival photograph courtesy of Jim Field.

——————————–

Home Sweet Home, c. 1720, East Hampton

Historic Structure Report by Robert Hefner

Abridged from Original Document, with supplemental photographs.

Prepared for the Board of Trustees, Inc. Village of East Hampton, by Robert Hefner, with research by Hugh R. King, 2004.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE ORIGINAL c. 1720 HOUSE

When Home Sweet Home was built around 1720 its exterior and interior appearance was quite different from the house we know today. Although the outward saltbox form was very similar, the original house had a different roof frame that did not have the overhang on the front wall. The exterior was covered with riven cedar clapboards. The large window openings measuring approximately 54” square were fitted with either casement sash or an early form of up-and-down sash. On the interior the house had a hall-and-parlor plan with an unheated lean-to across the back. Both the hall and parlor had large open fireplaces. The front entry probably had a simple, enclosed stairway. Interior walls were plastered or covered with wide pine boards. It was a plain and simple house in comparison to the house that resulted from the ambitious remodeling in the Georgian style that occurred about 1750.

The original architecture of Home Sweet Home had ties to the seventeenth-century with its narrow cedar clapboards, casement-type windows and hall-and-parlor plan with an unheated lean-to. The posts, girts and plates were cased and the ceiling joists were plastered over in the manner of the eighteenth century. The distinctive manner in which the lean-to was framed may be the signature of the original Home Sweet Home. The fact that the 1721 Mulford Farm Barn has the exact same lean-to frame was the deciding factor in assigning the date c. 1720 to the original construction of Home Sweet Home.

—————————-

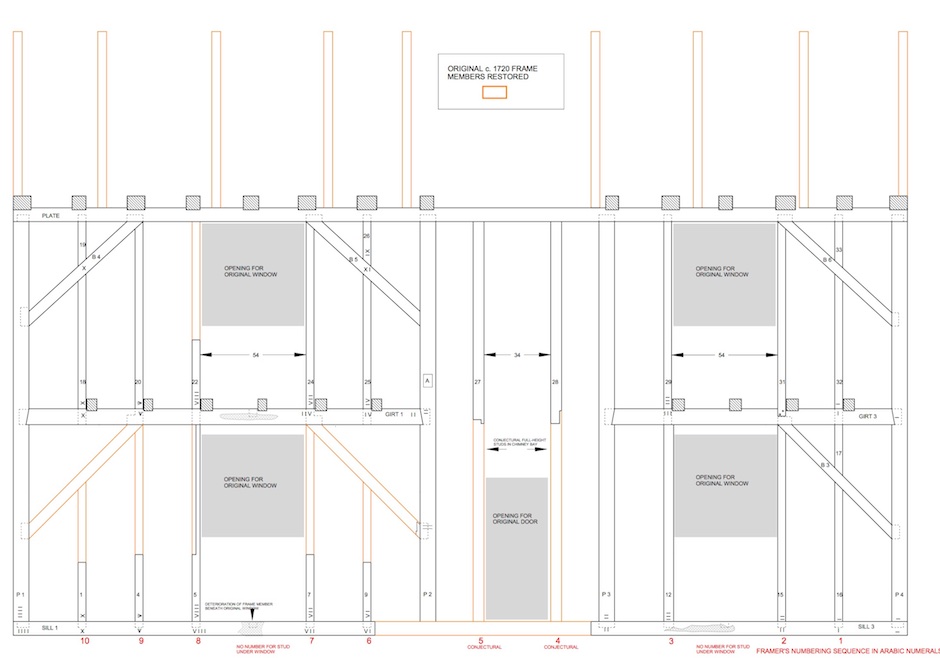

TIMBER FRAME (original c. 1720 construction)

The original timber frame consists of hewn oak timbers. Studs are boxed-heart saplings. The studs are typically spaced at intervals of 2’ – 5”. There are no summer beams. The floor joists are hewn timbers which follow the 2’ – 5” spacing of the wall studs. No timbers have chamfers or any other finish that would indicate they were exposed within the room. Posts, girts and plates are cased in pine boards.

—————————-

ROOF FRAME (original c. 1720 construction)

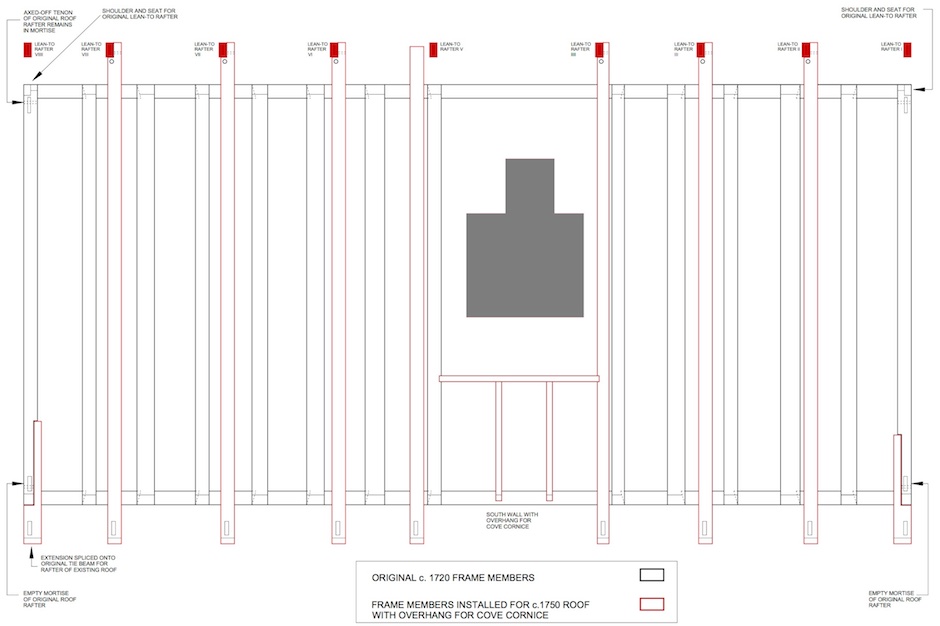

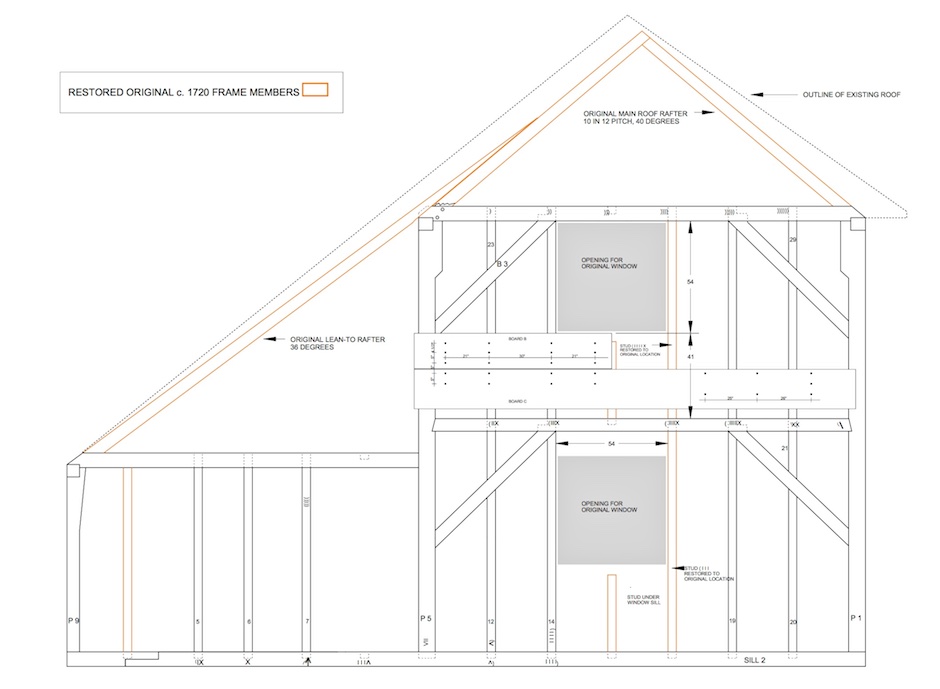

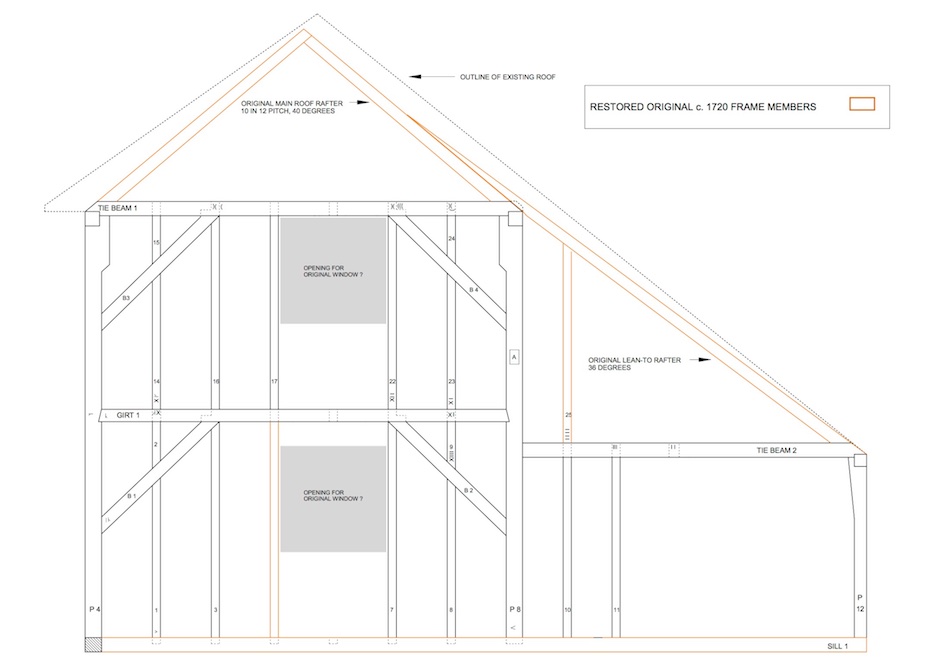

The original rafters of both the south and north roof slopes were removed during the c. 1750 remodeling of the house.The main two-story part of the original house (from post 1 to post 5 on the west wall and from post 4 to post 8 on the east wall) was covered by a triangular gable roof. The only physical evidence of this original roof is found in the end tie beams which preserve the mortises for the original rafters of the east and west gables. The north mortise of the west tie beam retains the rafter tenon left when the rafter was axed and broken off. The ends of the tie beams are beveled at 40 degrees indicating the 10 in 12 pitch of the original roof of the gable. (See Drawings 6 and 14.)

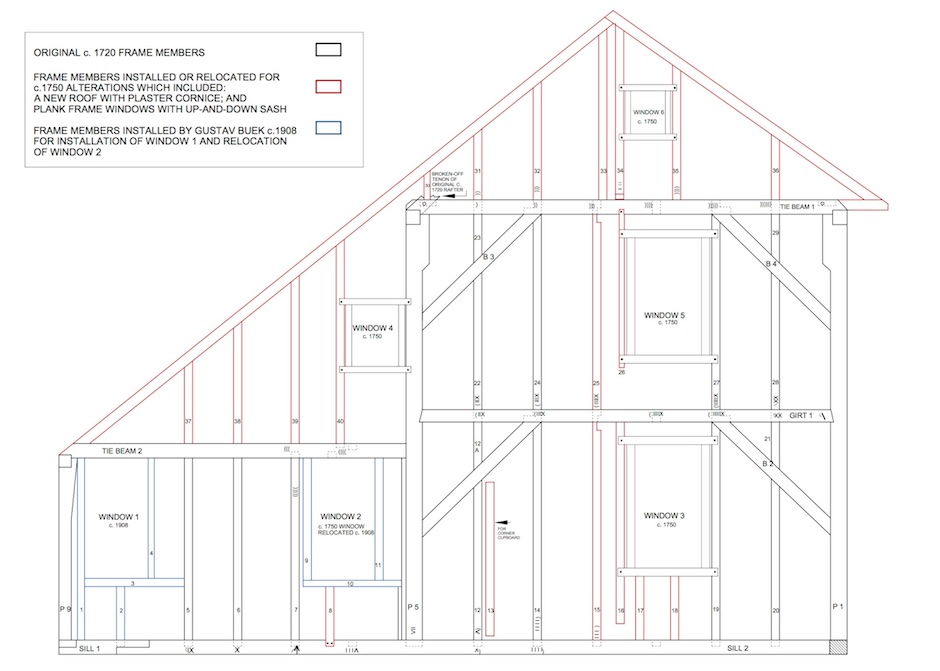

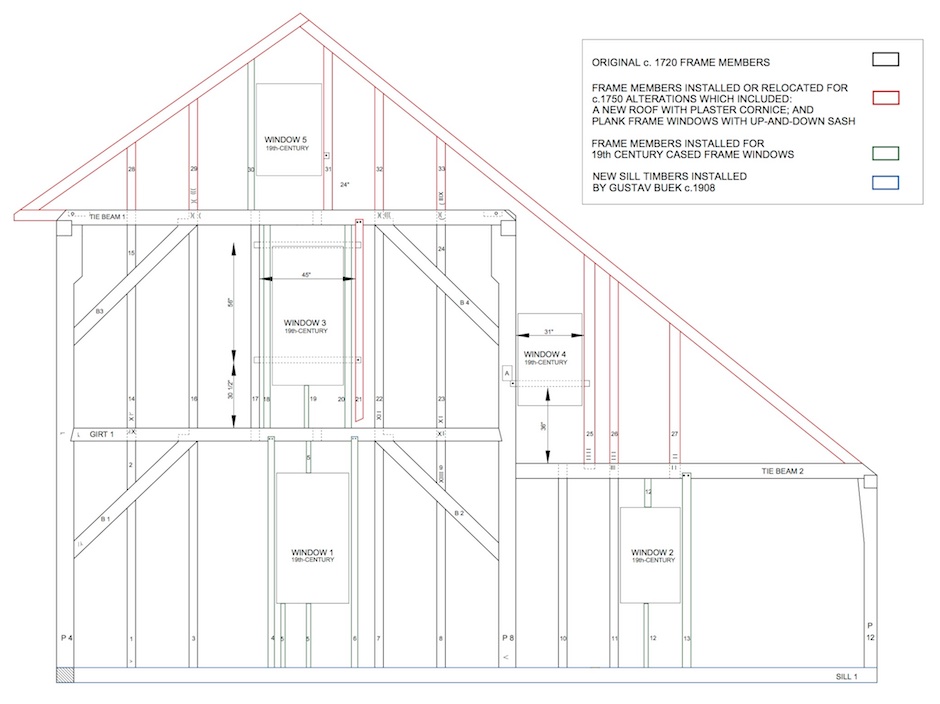

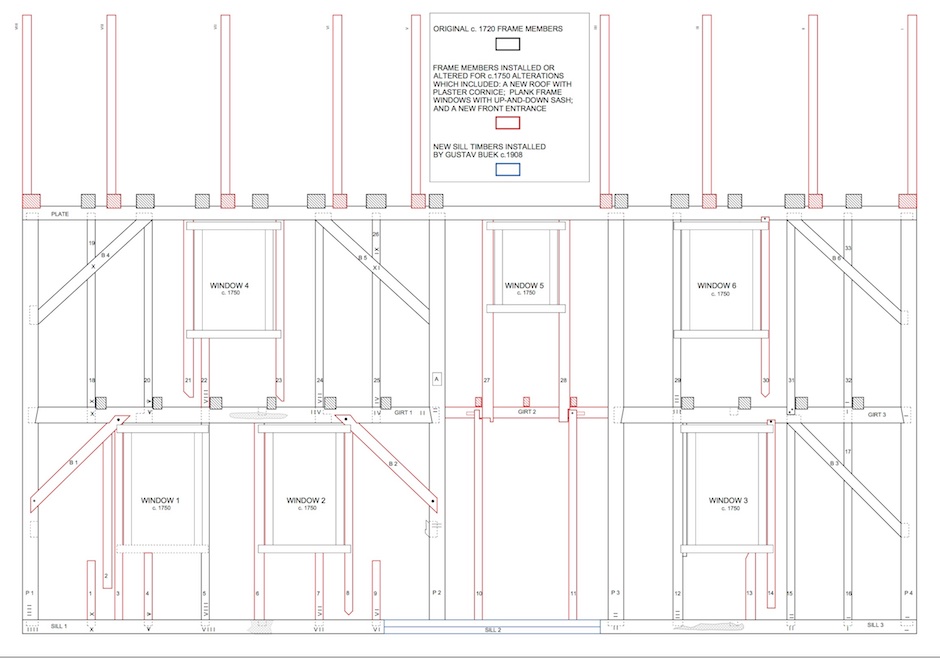

Drawing 6: West Wall Frame Indicating Alterations

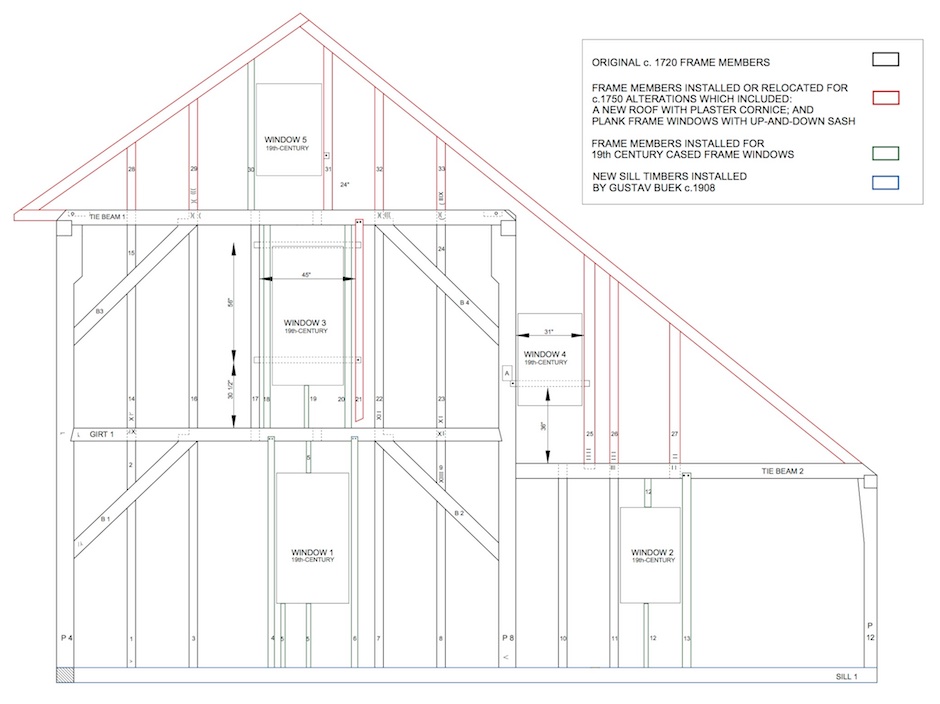

Drawing 14: East Wall Frame Indicating Alterations

The chimney bay tie beams have no rafter mortises. There are no markings on the plate to indicate where an original rafter would have been seated on it. The only conclusion is that the original rafters were seated on the plate with a bird’s-mouth and were positioned exactly as are the existing c. 1750 rafters. When the tie beams which carry the c. 1750 rafters were housed into the south and north plates, evidence of the original rafter seats was lost.

—————————-

ROOF FRAME OF THE LEAN-TO

We know that the original house had a lean-to across the north wall because the original west sill continues under the present lean-to and because there is no evidence of nailing of sheathing boards on the frame of the interior wall from post 5 to post 8. The lean-to tie beams (tie beam 2 on the west wall and tie beam 2 on the east wall) are original and document that the first floor of the existing lean-to is part of the original house. (See Drawings 6, 14 and 16.)

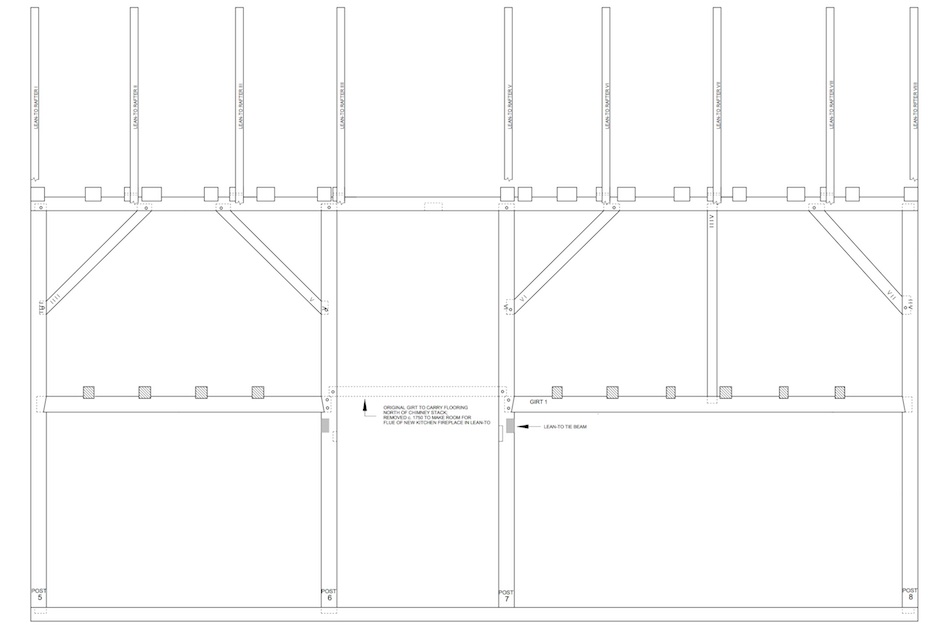

Drawing 16: Interior Wall Frame (From North)

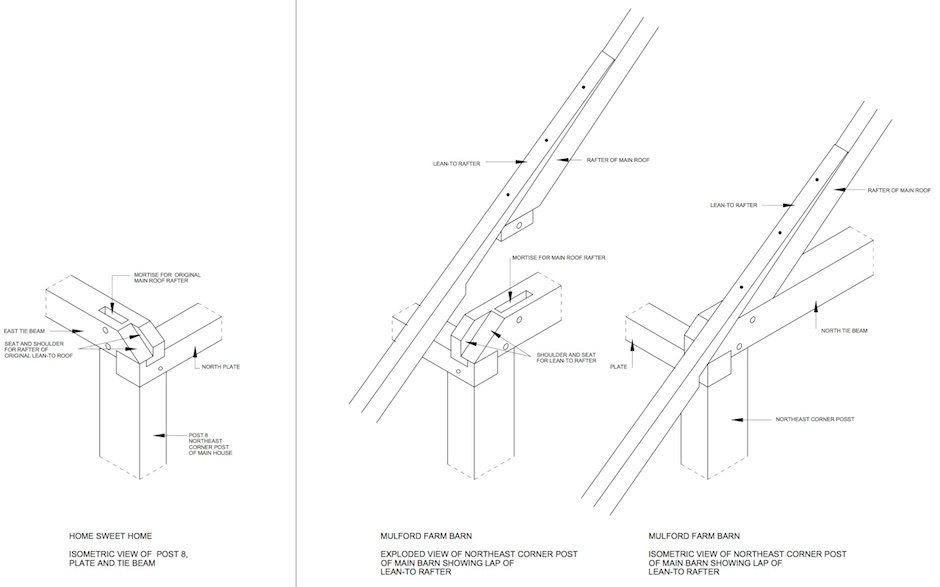

The only evidence of the original lean-to rafters is a shoulder along the bevel at the north end of the west and east tie beams of the main roof. This exact same condition is found in the frame of the c. 1721 Mulford Farm Barn on the adjoining property to the north. At the Mulford Farm Barn the lean-to rafter extends over the rafter of the main roof, bearing on the beveled end of the tie beam and continuing along the upper surface of the main roof rafter for a length of 5 to 6 feet. The ends of the tie beams have a seat and shoulder for the lean-to rafter identical to that found at Home Sweet Home. As at Home Sweet Home, the lean-to at the Mulford Farm Barn is part of the original construction. (See Drawings 17 and 18.)

Drawing 17: Comparison of Evidence of Original Lean-To Rafters at Home Sweet Home With Existing Original Lean-To Rafters at Mulford Farm Barn.

Drawing 18: Third Floor Frame Indicating Alterations

A lean-to rafter following the construction technique of the Mulford Farm Barn fits perfectly from the north ends of the Home Sweet Home lean-to tie beams to the north ends of the main roof tie beams. (See Drawings 8 and 15.)

Drawing 8: West Wall Frame — Conjectural Restoration of Original c. 1720 House

Drawing 15: East Wall Frame — Conjectural Restoration of Original c.1720 House

At the Mulford Farm Barn all rafters between the end pairs are seated on the plates with a birds-mouth. The corresponding lean-to rafters bear on these rafters and extend over them for a distance of 5 to 6 feet in the same manner as the end rafters. The original Home Sweet Home lean-to rafters between the end rafters would have had the same configuration.

Twelve heavy floor girders occur between the end tie beams. These have half-dovetail lap joints with the plates to counteract the force of the rafters. (See Drawing 18.)

—————————-

EXTERIOR WALLS (original c. 1720 construction)

Pine sheathing boards which remain from the original house document the original exterior clapboards. These boards contain nail holes which align in horizontal rows spaced 4 ½” to 5” and in vertical rows spaced 20” to 30”. These nails fastened clapboards which had an exposure of 4 ½” to 5”.

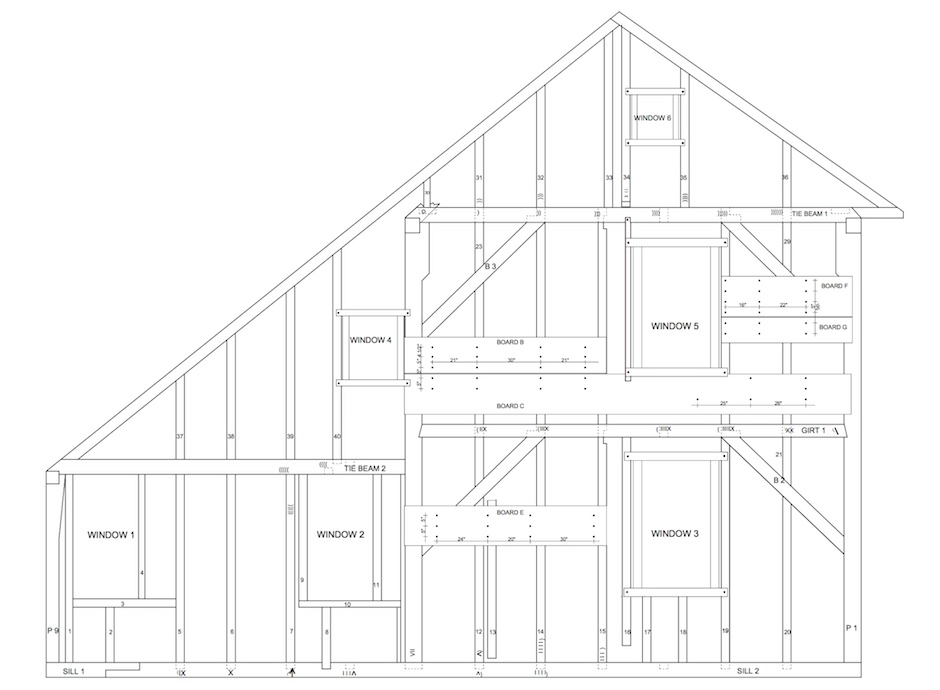

Drawing 7: West Wall Frame & Sheathing

Drawing 7 illustrates the nailing pattern of the original clapboards in five sheathing boards. Boards B and C are especially important because they remain at their original location. They provide clear documentation of four courses of 5” clapboards. Board B would have extended beneath the original second-floor window. Boards E, F and G were removed and replaced when the house was remodeled c. 1750. These boards document the same 4 ½” to 5” clapboards. (See Drawing 9.)

Drawing 9: Conjectural Restoration of West Wall of Original c.1720 House

Two wrought iron nails which fastened the clapboards remain in Board C. These where clinched over when the shingles were nailed on. The shank of these nails stood ½” proud of the sheathing board, indicating the thin riven cedar clapboards.

During the 1994 reshingling of Home Sweet Home, a few of what must have been the original clapboards were found recycled as kicker strips for the starter course of the c. 1750 shingles. These were riven cedar boards approximately 6” wide. (These clapboards were stored in the Pantigo Mill but were unfortunately removed during a clean-up of the mill.)

—————————-

WINDOWS (original c. 1720 construction)

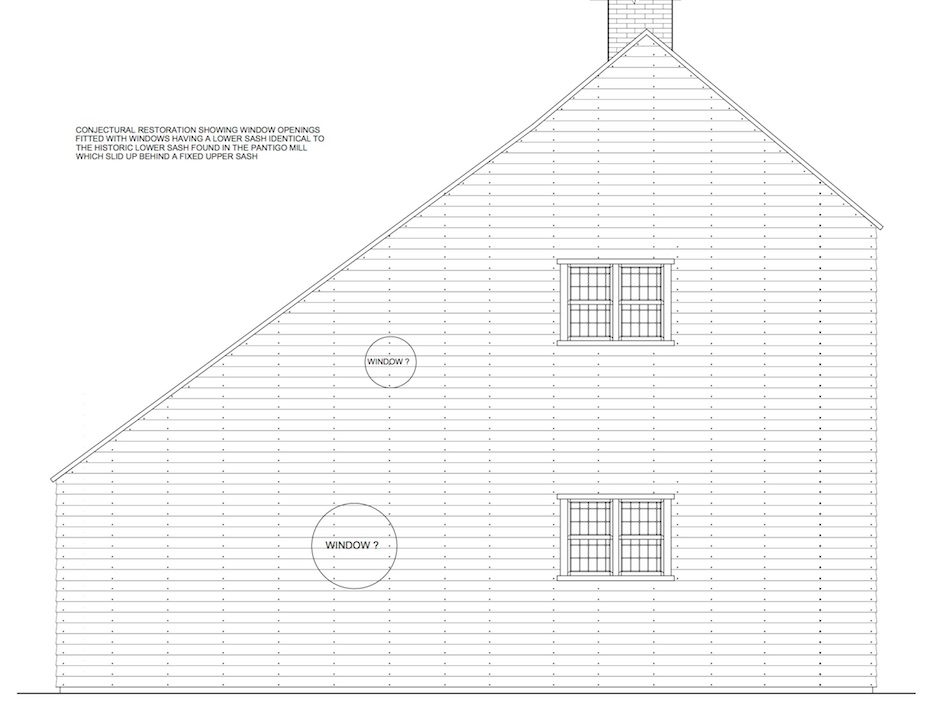

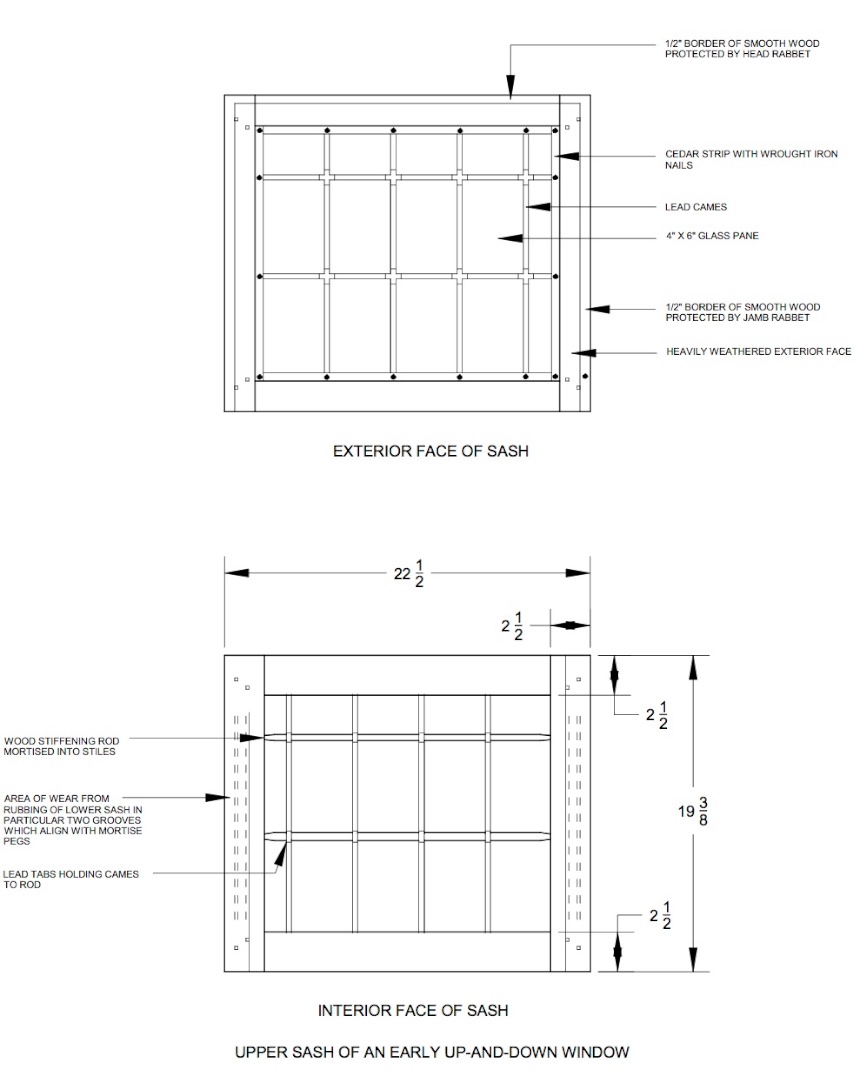

….In 1978 a rare window sash was discovered in the Pantigo Mill by Martin Weaver.[1] This small sash has a pine frame and leaded glazing of the type usually associated with casement windows of the 17th-century into the early 18th century. The markings and weathering on this sash clearly indicate that it was a lower sash that slid up behind a fixed upper sash. This sash is an example of a transitional window type between the 17th-century casement window and the typical 18th-century window with up-and-down sash similar to those found at Home Sweet Home today. Since Mr. Buek collected antiques, there is no reason to assume that this sash came from Home Sweet Home. But the fact that it fits exactly into the original window opening at Home Sweet Home provides the opportunity to speculate on what the original house may have looked like with this window sash. (See Drawings 11 and 12.)…

Drawing 11: Conjectural Restoration of West Wall of original c. 1720 House with Windows Having Up-And-Down Sash

Drawing 12: Early Sash Found in the Pantigo Windmill

[1] Martin E. Weaver, “A Short Note on an Early Sash Window Found at East Hampton, Long Island,” Association for Preservation Technology Bulletin, 1978, no. 1.

—————————-

FRONT DOORWAY (original c. 1720 construction)

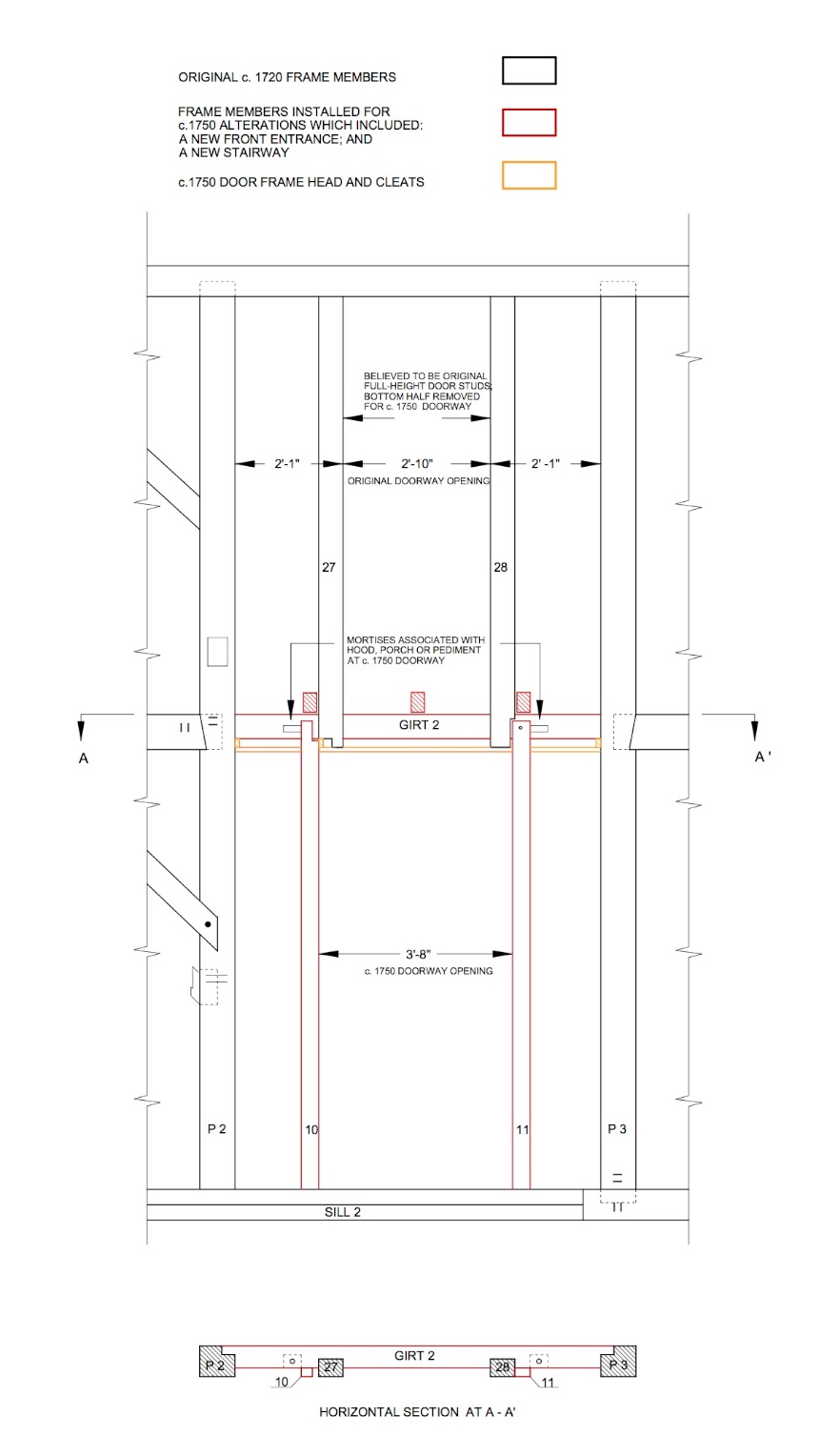

It appears that studs 27 and 28 on the south wall originally extended to the sill and formed the opening for the front door. The numerical sequence of the framer’s marks on the sill indicates there would have been two studs in the bay between post 2 and post 3. Studs 27 and 28 are centered in that bay and the distance of each from the posts (2’ – 1”) is characteristic of the original timber frame. Studs 27 and 28 are 5 ½” x 3 ½” in section while the typical original wall stud is 4” x 3” in section. This larger dimension suggests that studs 27 and 28 were two-story studs rising from the sill to the plate. There is no evidence of a horizontal girt between post 2 and post 3 in the original construction meaning that studs in the center bay had to be two-stories tall. The distance between stud 27 and stud 28 is 2’ – 10”. This is presumed to be the framed opening for the original front doorway. (See Drawings 3 and 4.)

Drawing 3: South Wall Frame Detail — Chimney Bay Frame

Drawing 4: South Wall Fame — Conjectural Restoration of Original c. 1720 House

—————————-

CHIMNEY (original c. 1720 construction)

Much of the original chimney stack remains intact. The original chimney had a large fireplace in both of the first-floor front rooms, but no fireplace in the lean-to. The original firebox in the west room is the most intact. The 8” x 12” oak lintel remains in place as do the north and south jambs of the original firebox that measured approximately 6’ 9” wide by 4’ 4” high by 2’ 4” deep. The fireplace presently in the west room was built inside this original firebox as part of the c. 1750 remodeling. The oven probably extended from this fireplace, but exactly where the oven was is not clear. Little evidence remains of the original fireplace in the east room. The oak lintel is missing, although a board set in the brickwork that was the south seat for the lintel indicates it was at the same height as that of the west fireplace. The c. 1750 firebox that was built within the original east fireplace was closed in and the whole chimneybreast covered with a mortar rendering in the late-19th century.

The original fireplace in the west room of the second floor remains entirely intact. The east room on the second floor never had a fireplace.

—————————-

INTERIOR (original c. 1720 construction)

The original house had a “hall-and-parlor” plan with a rear range of unheated rooms in the lean-to. The larger 18’ x 18’ west room would have been the “hall” where meals were prepared. An oven would have been built into the fireplace in this room. The smaller east room would have been the more formal parlor. The stairway within the front entry was probably enclosed within a board partition and was certainly far simpler than the existing front stairway. The existing stairway in the lean-to is part of the original construction. This is the only known original feature within the lean-to.

On the second floor the west chamber had a fireplace. The east chamber was not heated. The lean-to would have been one open space.

The interior featured posts, girts and plates cased with pine boards, vertical and horizontal board paneling on interior walls and lath and plaster on exterior walls.

Original paneling remains in the east room on both the first and second floor. This vertical paneling consists of wide pine boards with feather-edges alternating with wide boards that are grooved on each side to receive the feather-edge. The grooves are faced with a quarter-round bead. This same paneling is found on the west wall of the room below.

Original feather-edge paneling of the same type is found where it was recycled by the builders of the c. 1750 remodeling. This paneling was recycled as flooring in the attic along the south edge of the floor where it is nailed to the c. 1750 tie beams with wrought iron nails. These boards also preserve the paint finish they had when they were removed from the interior walls c. 1750. The boards retain one thin layer of a reddish pigment that is probably the red iron oxide known at the time as Spanish brown.

Original horizontal-board paneling remains within the lean-to stairway to the second floor. A feather-edge of one board fits into the beaded rebate of the board below. This paneling within the lean-to stairway was never painted.

Boards of the same type as the lean-to stairway horizontal paneling were recycled as exterior sheathing during the c. 1750 remodeling. Such boards were found fastened with wrought iron nails on the south and east walls.

[1] Since there was no number 17, the stud following 15 could most easily be identified by XX.

—————————-

THE HOUSE AS IT WAS REMODELED c. 1750

An ambitious remodeling undertaken around the middle of the 18th century essentially transformed Home Sweet Home into a new house that embodied many features of the Georgian style. As documented in the history section of this report, Captain Elisha Jones was most likely responsible for this transformation. Captain Jones lived in Home Sweet Home from about 1750 to 1764 when he died at the age of 48.

The work did not include any expansion of the house; it appears to have been motivated only by the desire for a stylish dwelling. This is most obvious in the reconstruction of the entire roof for the sole benefit of providing a front overhang where a plaster cove cornice could be installed. Other exterior changes that gave the house a new appearance included: new pedimented windows with large twelve-light and eight-light sash; a new front doorway that apparently was embellished with a hood, porch or pediment; and new shingle siding. It is likely that the entire new exterior was painted the reddish color known as Spanish brown.

Interior of West Parlor, Home Sweet Home, 2011.

Captain Elisha Jones’ aspirations for a refined dwelling environment for his family is evident in the west parlor with its elaborate woodwork featuring fluted pilasters, arched panels and a shell cupboard. Jones transformed this room from a “hall” where the cooking was done into the best parlor. The kitchen fireplace was moved into the lean-to. The west room on the second floor was similarly updated with new paneling. The attention given this room probably indicates another change in this household in that the parents’ bedroom moved from the first floor parlor to a second floor bedroom. The other primary interior change was a new front stairway with an open design, turned newel and balusters and a molded handrail. The final step taken by Captain Jones in creating the new fashionable interior was to paint almost all of the new woodwork Prussian blue.

—————————-

ROOF FRAME (c. 1750)

During the ambitious remodeling the original roof was removed and a new roof frame was built. The principal difference between the original roof and the new roof was the front overhang which allowed the front of the house to be embellished with a plaster cove cornice.

New third floor girders were installed that extended 20” beyond the plates to the front and rear. Extensions for the front overhang were spliced onto the original west and east tie beams. The roof overhang on the front wall allowed the façade to be embellished with a plaster cove cornice. On the rear wall the new girders provided an intermediate support for full-length rafters that extended from the north lean-to plate to the ridge. This form of roof, with continuous rafters supported by cantilevered attic floor joists, had become the standard lean-to roof construction in East Hampton by the middle of the 18th century. (See Drawing 18.)

A considerable amount of work was involved in installing this new roof: the original rafters were taken down; the wall studs of the attic story and of the second-story of the lean-to were taken down; the attic flooring was removed; new ends were spliced onto the east and west tie beams; seven new girders (7” square) were hoisted up to be installed in the third floor frame; nine new pair of rafters were installed; new or recycled studs were put in the attic and lean-two walls; and the new roof and wall framing was sheathed. At the end of this work, the only appreciable difference in the house was the plaster cove cornice. (See Drawing 6.)

It is possible that the original roof frame was damaged and this contributed to the decision to install a new roof. On the other hand, the new roof and plaster cove cornice were part of an ambitious program which included: significant changes to the timber frame elsewhere to accommodate all new windows and a new front door; removing and replacing the sheathing on nearly the entire house in order to make the changes to the frame; covering all walls with new shingles; building three new fireplaces and a new chimney stack for the new kitchen fireplace; installing a new stairway; and significant new interior paneling. Seeing the effort involved in constructing a new roof as part of this major remodeling makes it believable that it could have been installed for the purely aesthetic benefit of the plaster cove cornice.

—————————-

PLASTER COVE CORNICE (c. 1750)

The plaster cove cornice must have been the crowning element of the new Georgian exterior in the eyes of the man responsible for the c. 1750 transformation of Home Sweet Home. As noted above the only explanation for the new roof was to allow this plaster cove cornice.

The plaster cove cornice is a feature that is somewhat common on East Hampton houses of the eighteenth century but is quite rare elsewhere. In East Hampton a plaster cove cornice is found on: the Jonathan Osborn House, 9 Mill Hill Lane; the Isaac W Miller, 223 Main Street; the Osborne Office, 135A Main Street, the Osborn-Jackson House, 101 Main Street; and the David Mulford House, 177 Main Street. All of these houses date from the eighteenth-century but exact dates of their construction or of the possible addition of their plaster cove cornices are not known. This is a distinguishing feature of eighteenth-century East Hampton that deserves a separate study.

By comparison two eighteenth-century houses in Rhode Island have plaster cove cornices; there is only one plaster cove cornice in Connecticut and according to Abbott Lowell Cummings, “only three unrestored examples remain in Massachusetts.”[1]

The plaster cove cornice was a feature of English Medieval houses that was carried over in early English Georgian houses. Indigo Jones used a plaster cove cornice on the 1630 Peter Killigrew House in London and this was copied by other designers. In his Small Georgian Houses in England and Virginia, Daniel Reiff includes the plaster cove cornice as an element of the common vocabulary of small Georgian houses of the later 17th century in England.[2]

—————————-

EXTERIOR WALLS (c. 1750)

During the c. 1750 remodeling all of the clapboards and most of the board sheathing was removed from the exterior walls in order to make the changes to the frame for the new roof, windows and front door. Following this work all the walls were covered with long shingles. This is the typical evolution in East Hampton where shingles eventually replaced clapboards and weather boards as the preferred exterior wall covering.

When Home Sweet Home was shingled in 1995 the early shingles in the west gable were carefully removed and the nail holes marked. Some of the sheathing boards in the gable were new boards installed when the c. 1750 gable wall was framed. All nailing in these boards was associated with the existing 34” shingles, indicating that these shingles date from the c. 1750 remodeling. These shingles had been on Home Sweet Home for approximately 240 years.

The riven Atlantic White Cedar shingles were 34” long and were laid in 15” courses. Most shingles were 7” wide; the widest were 9” and the narrowest were 4”. The vertical-grain shingles were predominantly clear with some pin knots. They were fastened with wrought iron nails in a staggered pattern. One nail was approximately 1 ½” in from the butt on the left side and the second nail was approximately 1 ½” to 2” in from the top of the weather on the right side.

—————————-

WINDOWS (c. 1750)

One of the major changes made to Home Sweet Home during this remodeling was replacing the original mullioned windows which held either casement sash or early up-and-down sash, with the large plank-frame windows that remain on the house today.

The drawings of the south, west and east wall frames indicate how new studs were installed and how original studs were removed, relocated and altered for installation of the new windows. All new wall studs associated with these windows are hewn oak saplings. (See Drawings 2, 6 and 14.)

DRAWING 2: South Wall Frame Indicating Alterations

The windows on the west wall facing Main Street were vertically stacked in two columns attempting to make the asymmetrical saltbox façade as organized as possible (Gustav Buek altered this symmetry by moving the first-floor lean-to window 13” to the north and adding the northern-most window ca. 1908). On the south wall the two parlor windows interrupt a symmetrical window arrangement. Here the ambitious remodeling of the parlor interior took precedence, and the two windows are centered on the parlor wall.

The c. 1750 windows have plank frames made up of heart Eastern red cedar. Substantial jambs (4” x 4” in section) are mortised into a head and sill of similar size. The jambs and head are rebated to hold the fixed upper sash and to allow the lower sash to be raised. The plank frames are embellished with hand-planed profiles. The jambs and head have a quarter-round bead on the inner edge. The sill has a boldly molded profile. The five c. 1750 windows on the west wall retain the cedar pediments which fit over the head timber of the plank frame. A ghost along the top edge of the heads of the first-floor windows on the south wall document that these three c. 1750 windows also had pediments. The heads of the three second-floor windows are set behind the bed molding of the plaster cove cornice and have the same relationship to that molding as the first-floor windows had to their pediments.

Only the two windows of the west bedroom retain the original eight-light upper sash. These sash are 1” thick and have muntin bars that are 1 ¼” wide and 7” x 9” panes of glass. The original lower sash of these two windows had twelve lights. The large first-floor windows had upper and lower sash of twelve lights. The window in the west wall that illuminates the second floor of the lean-to had a single sash which could be raised up on tracks nailed to the inner face of the sheathing.

With the exception of the two original sash mentioned above, all other sash in the c. 1750 plank-frame windows are replacements dating either from the late 19th-century or from Gustav Buek’s c. 1908 renovation.

—————————-

FRONT DOORWAY (c. 1750)

The frame of the south wall in the chimney bay between post 2 and post 3 indicates that during the c. 1750 remodeling the original front doorway was replaced with a new doorway. As noted above, the original door studs extended the full height of the front wall from the sill to the plate and provided a 2’ 10” framed opening for the front door. (See Drawings 2 and 3.)

The following changes occurred in the framing of this bay during the c. 1750 remodeling: a girt was installed from post 2 to post 3 (gained and spiked to the inner face of each post) to carry three floor joists for the second-floor landing of the new c. 1750 stairway; the bottom halves of the original door studs were cut off at the soffit of this girt to make way for a wider front door; and new door studs were installed that provided a 3’ – 8” framed opening for the new front door, which would have been a paneled door.

The c. 1750 girt has two mortises in its outer face that appear to have supported framing of a hood, porch or pediment over the front doorway. Both mortises retain fragments of a deteriorated tenon and pin. The distance between the mortises is 4’ – 4”. The distance from each mortise to the chimney post is 12 ½”. With their symmetrical placement in relation to the door studs and with the tenons remaining in them, these mortises were certainly for some structure over the doorway. Given the effort made during the c. 1750 remodeling to embellish the exterior with a plaster cove cornice and window pediments, it would be expected that the new front doorway would receive a decorative cap of some kind.

When the south wall was reshingled during the third quarter of the 19th century, the entire c.1750 doorway and the window pediments were removed. The only fabric remaining from the c. 1750 doorway is the head of the door frame, a 1” pine board that notches around the door studs and ends at the chimney posts.

—————————-

EXTERIOR FINISHES (c. 1750)

The bed molding under the plaster cove cornice is the only exterior component to retain early pigment. There is a base layer of red pigment directly on the wood substrate. Over the red paint are multiple layers of white paint and a top layer of gray paint.

Home Sweet Home was described in an 1881 newspaper as being “whitewashed” and is depicted with a bright white exterior in an 1886 painting.[3] The fact that the c. 1750 shingles lasted for 240 years can be attributed to their being protected by paint or whitewash for much of that time. It is possible that the red pigment is original to the c. 1750 remodeling. The entire exterior may have been painted reddish brown with the red iron oxide pigment.

—————————-

CHIMNEY (c. 1750)

The major change to the interior plan made during the c. 1750 remodeling was moving the cooking fireplace from the west front room, the “hall”, into a new kitchen in the lean-to. A cooking fireplace with oven was constructed in the lean-to and a new chimney stack was built against the original stack resulting in the “T” shaped chimney above the ridge. New small fireplaces were built within the original large fireplaces in the hall and parlor.

—————————-

INTERIOR (c. 1750)

The single most ambitious undertaking of the c. 1750 remodeling that most clearly expressed the owner’s desire to create a refined Georgian house was the new interior of the front west room. This had been the “hall” with a large cooking fireplace. With the kitchen fireplace moved into the lean-to, this large front room could be transformed into a fashionable parlor. A new smaller fireplace was built within the large cooking fireplace. The room received three new windows, two of which were centered on the front wall. The fireplace wall was embellished with woodwork featuring arched panels and fluted pilasters. Fluted pilasters also framed the windows and the shell corner cupboard with glazed arched doors.

The smaller east front room also received a new smaller fireplace and new paneling on the chimney breast. The large west bedroom received a substantially new interior with paneling on the fireplace wall featuring bolection moldings. The east bedroom, which never had a fireplace, retained its original vertical-board paneling.

The new front doorway, with its apparent decorative hood, was a major new feature of the exterior, and within that entrance a new stairway was built. The original enclosed stairway was replaced with the present open stairway with turned newel and balusters and a molded handrail.

When the kitchen fireplace was constructed in the lean-to as part of the c. 1750 remodeling it is likely that the kitchen was flanked by a small bedroom and service room on each side, as it was in 1908 when Mr. and Mrs. Buek moved in.

———————————————————–

ALTERATIONS BY THE FAMILY OF ELISHA JONES JR.

Elisha Jones Jr., who died in 1788 at the age of 36, and his wife, Elizabeth Isaacs Jones, apparently did not have the resources to make any major changes to Home Sweet Home. One change appears to date from the early 19th-century when Elizabeth Jones and Sophia Jones were living here. The c. 1750 kitchen fireplace was rebuilt to have a smaller fireplace and a bake oven on the side. This is the kitchen fireplace and oven that remains today. When these changes were made, the chimney face was probably covered with wood paneling which would have included a door for the oven. It is possible that at this same time the kitchen ceiling was plastered for the first time.

—————————-

ALTERATIONS BY HARRY MULFORD, 1853-1900

Harry Mulford changed the appearance of the front façade of Home Sweet Home at some time before the earliest photographs were taken in the 1880s. The 24” riven red cedar shingles with an 11” exposure seen covering the front wall in the earliest photographs of Home Sweet Home must have been installed by Harry Mulford. These shingles were fastened with cut nails. When these shingles were installed the pediments were removed from the three first-floor windows and the front doorway (including the paneled door and the hood, porch or pediment) was removed. Harry Mulford installed a new doorway with a plain casing and a batten door. Mulford’s door frame retains cut nails that are the same as those fastening the red cedar shingles.

The loss of these Georgian decorative elements (the window pediments and doorway) gave the front of Home Sweet Home a much plainer appearance.

The nineteenth-century windows on the east wall which feature 2” casings fastened with cut nails appear in photographs of Home Sweet Home taken during the 1880s and 1890s. These windows installed by Harry Mulford have typical 2” casings fastened with cut nails. The fames of some windows have been rebuilt and casings replaced. The attic window is the only one to retain the complete 19th century frame and casings.

An 1881 article in the Brooklyn Eagle referred to Home Sweet Home as being “whitewashed.”[4] This confirms the exterior finish apparent in the 1886 painting of Home Sweet Home by Lemuel Maynard Wiles which shows bright white shingles and exterior woodwork.[5] The molding beneath the plaster cove cornice retains multiple coats of white paint.

It appears that the fireplace in the east parlor was bricked in during the ownership of Harry Mulford.

—————————-

ALTERATIONS BY GUSTAV BUEK, 1908 – 1927

Gustav Buek made a small change to the exterior that dramatically changed the character of Home Sweet Home. He reconstructed the front door to have the appearance of a seventeenth-century doorway with applied rustic cedar casings and a door with unpainted vertical boards, rosehead nails and iron strap hinges. A “Home Sweet Home” door knocker completed the antique picture. Buek had also installed a large hanging lantern and an antique door chime that gave the entrance even more of a romantic Colonial Revival character (these are now missing). The existing rustic door presents quite a contrast to the much more finished effect the c. 1750 paneled front door would have had.

Other exterior changes included installing the north window on the east wall and moving what is now the middle window on the east wall 13” to the north. Buek built the “L” extending to the east that enclosed part of the north wall.

Other exterior changes included installing the north window on the east wall and moving what is now the middle window on the east wall 13” to the north. Buek built the “L” extending to the east that enclosed part of the north wall.

Buek made only minor changes to the front rooms on the first and second floors. In the east parlor the fireplace had been bricked in by a previous owner. Buek installed paneling to cover the original fireplace opening that copied the design of the c. 1750 overmantel. To display his collection, Buek installed a closet in the northwest corner and a plate shelf around the room. Buek’s changes in the west parlor and west bedroom were confined to installing a display shelf over each fireplace. In the east bedroom Buek only added a doorway into the bathroom he had built in the lean-to.

In the kitchen the major change was to the appearance of the fireplace and oven. Mr. Buek removed wood paneling that had covered the face of the chimney stack in order to expose the brick. Buek installed the mantel and shelves around the room for displaying his collection.

Mary E. Bell, who had lived in Home Sweet Home in her youth, described the lean-to: “There used to be a pantry and bedroom at each end of the kitchen…”[6] The line of the partition that divided the small west bedroom from the kitchen service room is evident in the change from horizontal-board paneling to plaster in the west wall. Buek removed this partition to create a larger room which he called a “writing room.” On the east side of the kitchen the dividing partition was removed creating one larger bedroom.

The text and photographs of the various magazine articles praising the Buek’s Colonial home document the predominance of white woodwork.

Within the second floor of the lean-to Buek built a bedroom to the east and a bathroom to the west. For the first time Home Sweet Home had electricity, plumbing and a central heating system.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

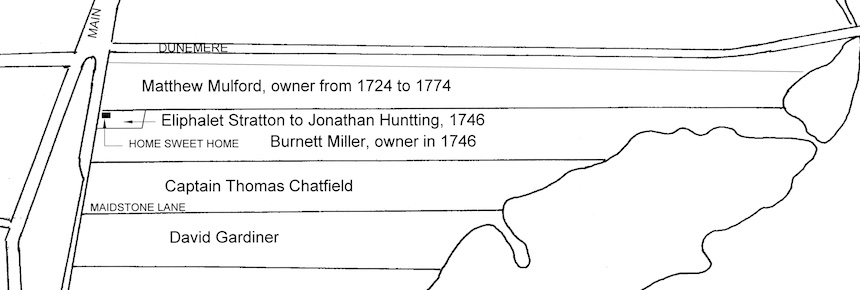

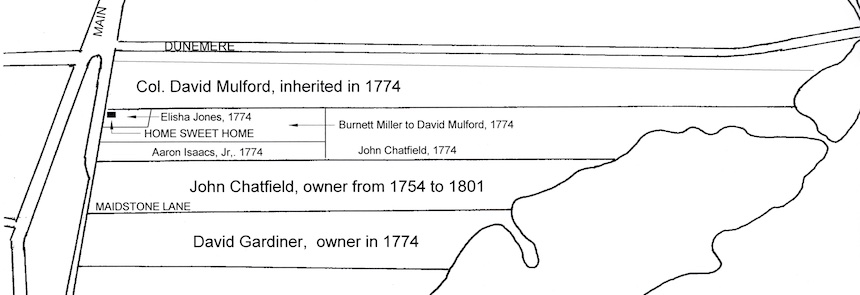

HOME SWEET HOME HISTORY

RALPH DAYTON AND ROBERT DAYTON HOME LOT, 1650-1712

——————————————–

——————————————–

——————————————–

——————————————–

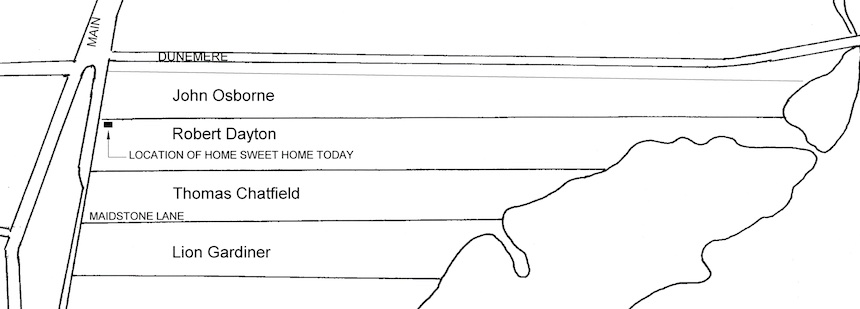

Home Sweet Home stands at the extreme northwest corner of what in the seventeenth century was the home lot of Ralph Dayton (1588-1658) and his son Robert Dayton (1628-1712).

The East Hampton Town Records provide a detailed description of the allotments of the early proprietors. These descriptions are not precisely dated, but were made by Benjamin Price between 1651 and 1663. [1] The “Records of the Allotment of Robert Dayton” describe the home lot:

…the home lot and addition containing fourteen acres more or less bounded by the street West and John Osborne’s home lott North and Hook Pond East and Thomas Chatfield’s home lot south.[2]

The amazing preservation of the Gardiner Home Lot and of Mulford Farm allow the location of the Robert Dayton home lot to be reliably identified. The East Hampton Historical Society’s Mulford Farm property is the front section of what was at this time the home lot of John Osborne. This identifies the northerly boundary of the Dayton home lot. Thomas Chatfield’s home lot to the south was adjacent to the Gardiner Home Lot, the boundaries of which remain intact today, south of Maidstone Lane. Knowing the acreage of the Dayton home lot (14 acres) and of the Chatfield home lot (11 ½ acres) and studying the lot lines on a contemporary tax map gives a fairly accurate sense of the southerly boundary of the Dayton home lot. The Dayton home lot frontage on James Lane extended from Mulford Farm down to the driveway to St. Luke’s Church and Rectory and extended east to Hook Pond.

———————————————————-

Content & drawings courtesy of Robert Hefner, Director of Historic Services, Village of East Hampton.

——————————————–

FOOTNOTES TO MAIN TEXT

[1] William H. Jordy, Buildings of Rhode Island, (N.Y.:Oxford, 2004), 468; J. Frederick Kelly, Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut, (N.Y.: Dover, 1963), 128; Abbott Lowell Cummings, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 134.

[2] Daniel D. Reiff, Small Georgian Houses in England and Virginia, (University of Delaware Press, 1986).

[3] The Brooklyn Eagle, August 4, 1881, p. 3; Ronald G. Pisano, Long Island Landscape Painting, 1820-1920, (N.Y.: Little, Brown and Company, 1985), 95.

[4] The Brooklyn Eagle, August 4, 1881, p. 3

[5] Ronald G. Pisano, Long Island Landscape Painting, 1820-1920, (N.Y.: Little, Brown and Company, 1985), 95

[6] The East Hampton Star, April 10, 1941.

[7] Minutes of the Board of Trustees, Village of East Hampton, December 1, 1930.

————–

FOOTNOTES TO HOME SWEET HOME HISTORY

[1] Records of the Town of East Hampton, Volume I, (Sag Harbor, N.Y.: John H. Hunt, 1887), 432.

[2] Ibid.,465.

————————————————–

VISIT POST BELOW FOR PHOTOS & POSTCARDS OF HOME SWEET HOME

AAQ / Content / Landmark: Home Sweet Home, East Hampton (click)

————————— ADDENDUM —————————

Home Sweet Home, west elevation, 2014.

Mulford House, west elevation, 2014.

Mulford House, Home Sweet Home & Pantigo Windmill, 2015.

Archival photograph by C. Manley DeBevoise, courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Home Sweet Home Cigarette Card from George Arents Collection. Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

———————————-

Photographs, except archival, by Jeff Heatley.

____________________________________________________________