13 Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol & the 1964 World’s Fair

Special to AAQ East End by Jan Garden Castro

In revisiting the censorship of Andy Warhol’s art fifty years ago at the opening of the 1964 World’s Fair Pavilion in Queens, the Queens Museum sheds light on its own history, exposes the conditions that create censorship, and contrasts the power structures & aesthetic tastes of both periods.

There is a back story that’s never been told. We all know that Philip Johnson designed the New York City Pavilion’s “Tent of Tomorrow” exterior, but few know that his partner David Whitney was an avid art collector who helped him select ten mostly gay men for prominent 20 x 20-foot commissions around the round building. Robert Indiana created his famous EAT sign – three big electronically-lit letters, Roy Lichtenstein created a new face, Robert Rauschenberg an ad motif, John Chamberlain a car parts motif, etc. Andy Warhol selected thirteen wanted men from a 1962 New York Police Department booklet. He enlarged their mug shots and formed a chessboard of front and profile images for his 20 x 20 spot. Choosing to feature the heads of New York criminals on a public building – for Warhol’s first and only public art commission – was a subversive move. Warhol created his electric chair series around this time, and these are two serious subjects unlike others during his career. 1962-64 was a time with some civil rights activity and saw the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. 1964 was a time for civil rights issues, but gay rights and the rights of accused criminals and those on death row were not yet being discussed. Warhol, with his electric chair and most wanted series, was the only artist or person of note to raise these issues obliquely in his art.

Andy Warhol, Thirteen Most Wanted Men, silkscreen on canvas, 20 x 20 ft. Installed on the exterior of the New York State Pavilion. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol, Thirteen Most Wanted Men, silkscreen on canvas, 20 x 20 ft. Installed on the exterior of the New York State Pavilion. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Even though Warhol’s idea for the Most Wanted Men grid was known, it was painted over in silver 48 hours after it was installed in 1964—and before the Fair opened. Many think that then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller personally called for this art work to be removed from the building just as he and his father had destroyed “Man at the Crossroads,” a mural they commissioned for the Rockefeller Center from artist Diego Rivera in 1932. Warhol probably thought the censorship was the work of Robert Moses, and the artist, ironically, began a series of heads of Moses, one of which is installed in the park near the Queens Museum. It was a time when Robert Moses was changing the map of New York City, for better and/or worse, by inserting highways, overpasses, bridges, and tunnels in ways that helped to unify the boroughs and also to create new bottlenecks of pollution and congestion. To some, Moses was a hero and to others he was a villain cutting through and destroying old neighborhoods. Interestingly, too, Warhol began his portraits of Jacqueline Kennedy around this time (before and after JFK’s murder), and he also painted a portrait of Nelson Rockefeller and his wife Happy.

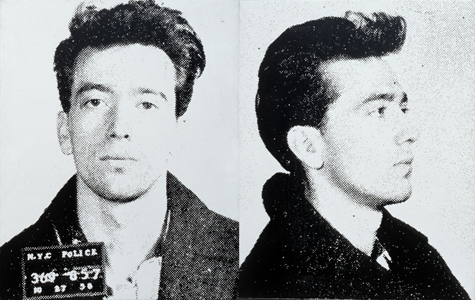

Andy Warhol, Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr., 1964. Acrylic and liquitex in silkscreen on canvas. Image given courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main. Photographer: Axel Schneider, Frankfurt am Main © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol, Most Wanted Men No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr., 1964. Acrylic and liquitex in silkscreen on canvas. Image given courtesy Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main. Photographer: Axel Schneider, Frankfurt am Main © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

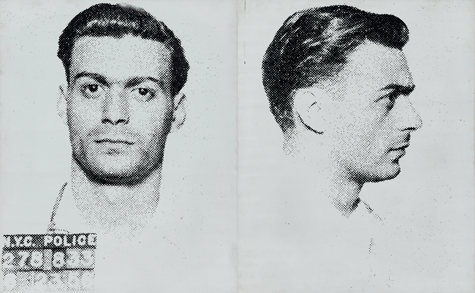

The exhibition covers the history of Warhol’s creation of the 13 Most Wanted images, press clippings from the period, the censorship of the image, and Warhol’s other works from the period. These include his Brillo and other boxes, shown the day before the Fair opened, and his first Screen Test series titled Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys. This super-slow film series – shown for its first complete run at this Queens exhibition – was both the beginning of Warhol’s screen tests and a nice contrast to the Wanted series since both feature young white “wanted” men with interesting faces. Following the censorship, Warhol produced another set of the Most Wanted Men paintings in the summer of 1964; nine of these are shown as part of the 175 or so objects that complete the exhibition.

Andy Warhol, Most Wanted Men No. 10, Louis Joseph M., 1964. Silkscreen on linen, 48 x 38 7/8. Image courtesy Stadtisches Museum Abteiberg. Photography by Achim Kukulies. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol, Most Wanted Men No. 10, Louis Joseph M., 1964. Silkscreen on linen, 48 x 38 7/8. Image courtesy Stadtisches Museum Abteiberg. Photography by Achim Kukulies. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The exhibition charts the creation, the destruction, and the social context of Warhol’s Most Wanted Men. The viewer can appreciate the interrelations of underground and establishment; art, protest, and gay life; painting, sculpture, and film in a key year for Warhol. Warhol had the last word in a New York World Telegram story by Kit Kincade published on July 6, 1965: “ ‘I don’t believe in anything, so this painting [painted over] is more me now,’ he confided.” Warhol was famous, in part, because he was a keen observer of the social milieu of his times, and he moved quickly among his fascination with high and low people, things, and art-making while at the same time denying that he was doing anything special.

———————————————————-

— Jan Castro (www.jancastro.com) is an art historian and author based in Brooklyn. She is is Contributing Editor at Sculpture Magazine; her “In the Studio” blog is posted at Sculpture.org.

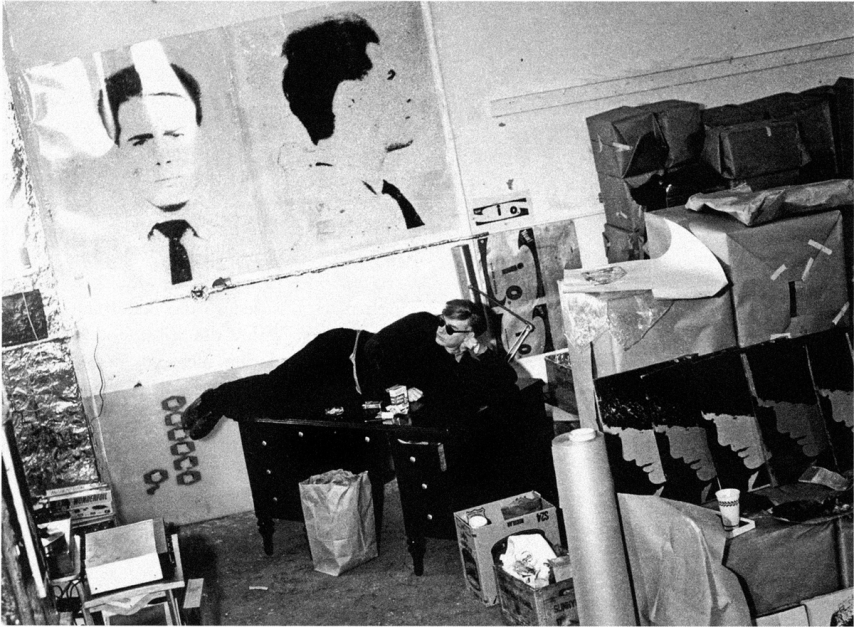

Billy Name, Untitled 1964, reprint 2014, Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Billy Name, Untitled 1964, reprint 2014, Archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This exhibition was developed collaboratively by the Queens Museum and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

————————————-

13 Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair

April 27, 2014 – September 7, 2014

————————————-

________________________________________________________