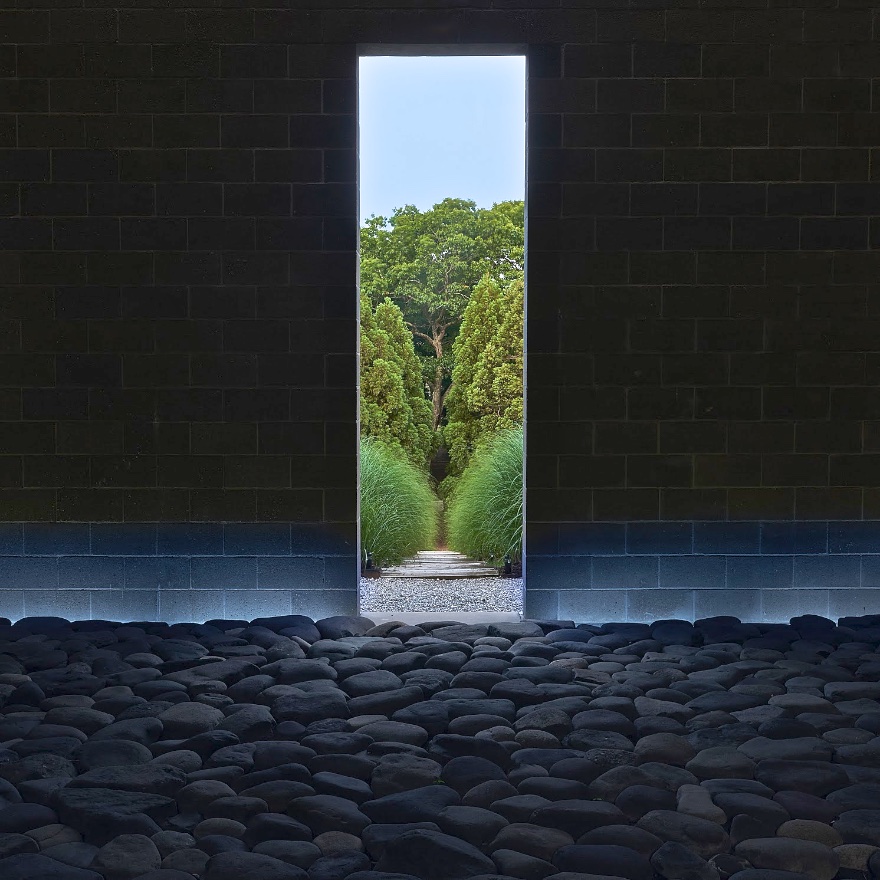

Grounds seen from inside the Knee building entrance. Photo © Kristian Kruuser

AAQ East End

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~`

Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center:

Containing the Universe

By Jan Garden Castro

Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center encompasses more than the eye can see, but seeing, hearing, and otherwise bringing the senses alive is part of a deeper consciousness that this theater master instills in his international guests and residents. Wilson has spent a great part of his life developing theater works like Einstein on the Beach, his collaboration with Philip Glass, which premiered on July 25, 1976, at the Avignon Festival in France, and was presented that year in Hamburg, Paris, Belgrade, Venice, Brussels, Rotterdam, and New York. “As a young French boy, I loved Bob’s pieces immediately — their elegance and sense of humor — his way of being serious with a door always open to irony and fun,” offered Patrick Bensard, Founder of the Cinémathèque de la Danse, Paris. “Mystery was the key dimension—no explanations, no analyses, no words…only the emotion that suddenly jumped on us.”[1]

Over forty years later, mystery and creativity abound at The Watermill Center’s lushly-cultivated eight and a half acres of land, the present U-shaped building atop a hill, and structures that rise briefly for The Center’s annual summer benefit. Sites have been chosen for new permanent structures that will harmonize with the landscape. Watermill encompasses world arts and cultures, including Mr. Wilson’s personal museum-quality collection of about 8000 objects spanning 5000 years. At The Watermill Center, people live intensely in the present moment yet also incorporate the past and the future.

The Watermill Center’s U-shaped building. Photo © Kristian Kruuser, 2015

Watermill is an extraordinary accomplishment considering that it was a Western Union laboratory built in 1925, abandoned in 1965, and rat-infested when Mr. Wilson bought it in 1989. All that remains of the original structure is its U-shaped footprint. It has taken years of planning, fund-raising, design, construction, and curating to produce the present building of corrugated zinc, grey cinder block, poured concrete and glass which is filled, room by room, with select pieces of priceless art. The sash windows are recessed into the facade with black frames accentuating the depth of the frames. These echo the windows in the original building. Mr. Wilson built the entire central Knee building – a vertical area thirty-feet wide, thirty-five-feet deep, and thirty-five-feet high – in wooden frames and fabric during the summer of 2003. The Knee building serves as a main entrance. Its open doorways – without doors – face east and west, so the sun enters and sets through the building. The floor of this area is made of river stones and is open to the elements. A new residence is slated for completion in early 2018. Its exterior, including the roof, will be shingled wood and glass.

We meet Robert Wilson as he is supervising work on the grounds in preparation for The 24th Annual Watermill Center Summer Benefit & Auction on July 29, 2017. Staff and visiting artists along our paths are pruning, planting, weeding, mulching, and otherwise tending the rich array of plantings, which include everything from indigenous blueberries to red Japanese weeping maples, towering beech and Japanese pine trees, and boxed beds of tall grasses (miscanthus sinensis or maiden grass). Wilson notes the way beech trunks reflect different kinds of light. A small army of workers and the maestro cultivate nature’s harmony and variety. Nixon Beltran, a handsome, tattooed Colombia-born dancer, choreographer, and yoga teacher, is the Watermill Center Manager. He supervises the horticulture, which mixes indigenous with cultivated plants.

For the Benefit & Auction, visitors will enter along a pathway strewn with fragrant pine needles and hung with giant tapestries by Jared Madere titled “Melbaumme, Zoey Carves The River, Every Rose.” A more intimate entrance to the estate is an allée lined with tall bamboo (Phyllostachys aureosulcata). Past the bamboo is a zinnia garden, whose bright colors were favorites of artist Clementine Hunter. Mr. Wilson tells us her story. She grew up picking cotton on the Henry family’s Melrose plantation in southern Louisiana. In her 30s, her mistress gave her some oil paints, and she began creating a visual record of plantation life – picking cotton, the cotton gin, harvests, and funerals. At age 12, when he visited the Melrose Plantation with his parents, Mr. Wilson spent $2.50 to buy Hunter’s original art Wash Day. As an adult, Mr. Wilson has championed Hunter’s work and the ways that it documents the daily life and rituals of an era that no longer exists. At Watermill, he has built a house like the one in which Clementine Hunter lived, and a zinnia garden as well. Hunter’s murals are inside. Her original dwelling — a rectangular base with a slanting roof – was built by her ancestors, slaves from Ghana, in the 1880s.

Beech grove with stone columns from Ming era 9th Century AD and other cultures/eras. Photo by Jan Castro

Beech grove with stone columns from Ming era 9th Century AD and other cultures/eras. Photo by Jan Castro

As we walk through the grounds, Mr. Wilson discusses the sacred carved stones that are set into the woodlands. He tells us about waiting years to buy three tall stones from Sumba, Indonesia from a woman in Atlanta to complete the grove of standing stones he acquired from the same site. I am especially attracted to the Ming columns from China (368 – 1644 AD) set among the beech trees. There is a 9th Century demon head from Java made of red volcanic stone. Stone tables were built to shelter the buried bodies of kings, and to later hold their bones. Rising near the main building is a monumental wooden column signifying the burial place of Mapai, an aristocrat from the Punan Bah, a vanishing ethnic group in Borneo. Ida Nicolaisen’s tribute essay about this monument, a Keleriang burial column, notes, “To the Punan Bah [people],…it represents an embodiment of their culture, symbolically tying death, rebirth, and procreation neatly together. It is a repository for the dead but also a statement about life.”[2]

Keleriang burial column from Punan Bah culture. Photo © Lovis Ostenrik

Part of Watermill borders the Peconic Land Trust, a non-profit group dedicated to preserving Long Island’s working farms, natural lands, and heritage. Mr. Wilson is doing his part to encourage land use that cultivates ideas as well as Long Island’s history.

A hefty book titled THE WATERMILL CENTER, A Laboratory for Performance, Robert Wilson’s Legacy (Daco-Verlag, 20011) presents over 360 pages of photos, drawings, and texts that begin to document some of its history, including the building’s stages of use, design, and rebuilding. Wilson sees the building’s bottom layers – a big kitchen and dining areas, a library, and an art storage area – as parts of its foundation. The big outdoor and indoor rehearsal spaces and work areas, including a room with computer stations, are in the center, as part of daily life. An upper area with Mr. Wilson’s living and work areas, terraces, and sky offer, as it were, communion with air spirits, and higher thoughts.

Aerial views of The Watermill Center main building. Photo © Lovis Ostenrik

Watermill’s main building sits on a hill and its shape fits into the now-landscaped entrance and terraces that surround it. Just as the rooms seem to flow or float, one into the other, without doors or obstructions, the windows and views provide an easy relationship between inside and outside. Mr. Wilson has shaped the entire configuration of architecture, space, and nature, earth and sky as part of the cosmic order of things. Roger Ferris and Partners architects have designed a new residence adjacent to the main property to be completed 2018 that will update notions of the New England barn.

Above all, Watermill is designed as a locus where talented diverse residents find harmony and community. At Watermill, artists from different geographic locations and cultural backgrounds freely explore and practice their arts. Jȍrn Weisbrodt, in the essay “A Future for Watermill,” projects, “The Watermill Center will endure not as a palace of stone but as an embassy of free thought for future artists.” As opera singer Jessye Norman, a friend of Mr. Wilson’s since their Paris days, put it, “We might come across the notion that an awakened spirit could well be the real meaning of life, that the exploration of one’s own imagination is indeed one’s real life’s work. Watermill provides a true breeding ground for this exploration, and with Robert Wilson as the guiding light for these many and varied journeys, the true art of the artist is born, reborn, and born again.” Mr. Wilson told me, “As André Malraux said, ‘We need to balance protecting the art of the past and the art of our time, the art of our nation and the art of all nations.’ It is more important than ever to keep the doors open.”

Aerial views of The Watermill Center main building. Photo © Lovis Ostenrik

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thank you to Robert Wilson for his generous tour of The Watermill Center, and thank you to Danielle Mayer for facilitating this and for putting together the photographs.

———————————————-

[1] Bensard email to Castro, 8.21.17. Also see http://artsarena.org/events/celebration-of-the-cinematheque-de-la-danse/ http://www.watermillcenter.org/events/bensard/

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/13/arts/dance/13chil.html

See also http://www.watermillcenter.org/ and www.robertwilson.com/

[2] Ida Nicolaisen, “A Column of Spirit: Linking Art and Science in Central Borneo,” The Watermill Center, A Laboratory for Performance, Robert Wilson’s Legacy. Stuttgart, Germany: DACO-VERLAG, 2011, p. 251. All quotes not from Mr. Wilson are from this book.

————————————

Visit: AAQ Construction: The Watermill Center — Plans for Watermill Artist Residence

____________________________________________________________________