Our Mission

Our Mission

Our mission is to cultivate, preserve, and share these lands, buildings, and stories — inviting new thought about the importance of food, culture and place in our daily lives.

Once a Native American hunting and fishing ground, Sylvester Manor has since 1652 been home to eleven generations of its original European settler family. It reflects a remarkably intact history of America’s evolving tastes, economies and landscapes.

Over time, the place has been transformed from a slaveholding provisioning plantation to an Enlightenment-era farm, then to a pioneering food industrialist’s estate and today to an organic educational farm responsive to, and supported by, our neighbors and friends worldwide.

In light of this history, we envision a farm, a community, and a world where people celebrate food, arts, and inventiveness in the everyday, with a spirit of fairness and joy.

Sylvester Manor

The Sylvester Manor house is in fact a collection of several building and remodeling efforts spanning several hundred years, responding to the changing tastes and needs of its many descendant residents. The original c. 1652 house, to be built of “six or seven convenient rooms” served the corporate needs of the four sugar partners and provided a home for Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester, their eleven children and most likely several slaves and indentured servants. Aside from a brief reference to a second floor porch chamber mentioned in Grizzell’s 1685 will, there are no known descriptions of the 17th century plantation-era residence.

As far as we know, the original house remained intact until c. 1737, when Nathaniel’s grandson, Brinley Sylvester, who waged a long legal battle to claim his inheritance, built a new residence close to the original home site. Though the new construction repurposed several beams, doors and other architectural elements from the original dwelling, Brinley’s was a new, fashionable Georgian residence that cast off the family’s hybrid Dutch, new-arrival roots in favor of a style that firmly reflected the sophistication and prosperity of the English leisure class in North America.

Visitors to the Manor will still see in the south-facing front elevation of the current house the symmetrically placed “six-over-six” windows, central doorway, hipped roof and dormers and, inside, the interior features of the Georgian-period residence. Brinley repeated the rigid geometrical design of his house in the 2-acre adjoining garden, where the orchard, axial boxwood paths and formal rectangular garden beds of herbs, vegetables and flowers were laid out in a combination of kitchen and commercial use and aesthetic delight.

The house remained relatively unchanged until the mid-1830s, when proprietor Samuel Smith Gardiner and his wife, Sylvester descendant Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu Gardiner, made several modifications. Gardiner, a lawyer, adapted the house to serve the needs of his busy law practice: a first floor bedroom was remade into a study, with the addition of an eastern exterior side door and inner vestibule to accommodate waiting clients. The kitchen, currently the dining room, was expanded in an “El” to the north, and a cream-colored paint was applied over the Prussian blue and white lead pigment first applied by Brinley Sylvester in c. 1737. To this day, these are the only two coats of paint to cover the Manor’s wainscot paneling in the parlor and the paneled upstairs bedroom.

Two Gardiner daughters, first Mary, then Phoebe, married Harvard professor Eben Norton Horsford and the house, called Abbey Manor by the family, became a summer residence. Life in Cambridge placed the family in the inner circle of the American cultural and intellectual elite, many of whom were frequent Manor guests. During the late-19th century, Shelter Island became a summer salon of sorts as H.W. Longfellow, Asa Gray, Sara Orne Jewitt, John Whittier Greenleaf and other friends spent summer vacations with the family.

Cornelia Horsford, daughter of Eben and Phoebe, had been mistress of the Manor’s gardens for many years before inheriting the property in 1903. Like Brinley Sylvester before her, Cornelia wanted a home that confirmed her place in society and her times; the Colonial Revival movement, a celebration of traditional American roots and values, suited the pedigree-conscious Cornelia perfectly. In 1908, with resources left from her father’s successful food patents, she hired Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial, in Washington, to design a large Colonial Revival addition to the existing house and adapt its older interiors. Bacon widened the central hall and main staircase, installed a new kitchen in the basement, added symmetrical covered side-porches to the east and west, and more than doubled the size of the house with a significant addition to the back. In a nod to the Sylvester’s Dutch origins, Bacon included picturesque blue and brown Delft tiles in his fireplace redesign scheme.

The last resident “Lord of the Manor” was Andrew Fiske, Cornelia’s nephew. Inheriting the Manor from his aunt in 1944, He began a program of modernization that brought the house fully into the twentieth century. Cornelia’s first floor butler’s pantry was replaced with a modern kitchen, with its basement predecessor reinvented as a flower room for his wife, Alice Hench Fiske. The antique coal-burning furnace was replaced by a contemporary gas burner, though the last Sylvester Manor coal delivery, made over a half-century ago, still rests where it was delivered in the southwest corner of the basement. And in the early 1950s, the Fiskes installed a swimming pool near the garden, where it is flanked by the same boxwoods planted by Brinley centuries ago.

The Grounds

The 1651 purchase of Shelter Island included all of its 8,000 acres. Over time, as land was distributed to heirs, sold to newcomers, and needs shifted, the property gradually diminished in size and scope. What now remains is the 243-acre former plantation core, encompassing farm fields, wet and wood lands, formal gardens and grass lawns, numerous barns and buildings, and the Manor house.

In addition to the central structures at the heart of the property, the extended Manor grounds hold a wealth of diverse cultural inventories that directly link the land with social and ethnic interactions, changes in agricultural and commercial use of the property, religious persecution and tolerance, racial inequities, and how these factors collectively impacted the lives of people living and working at the Manor. Their stories live in the land.

On these grounds are the remains of ancient hunter-gatherer Manhansett Indian settlements, predating European arrival by at least one thousand years. A short distance to the south of the residence is a small rises of land between the driveway forks, where by tradition as many as 200 servants and laborers of the Manor are interred. The burial ground lies amidst a huge stand of white pine trees that were planted at the turn of the last century, when it was believed that their clean scent filtered the air and protected against some diseases.

To the west near the creek lies another Manor cemetery, commemorated by Cornelia Horsford in 1884 to all residents of the property over the centuries, including several persecuted Quakers who found refuge with the Sylvesters in the 17th century. There are no headstones for any of the founding members of the Sylvester family here. Today, the site is the warm-weather meeting grounds for Shelter Island chapter of The Society of Friends.

The property has always revolved around food and land. The fields of the Manor have been in agricultural use for at least 360 years, cultivated for plantation, commercial and subsistence production. The “Watermelon Patch”, located to the north of the Manor House, is believed to be the first field put to culture in the 17th century. At one time, the Sylvester fields spread north toward Dering Harbor, east to Coecles Harbor, and south to the Menantic area.

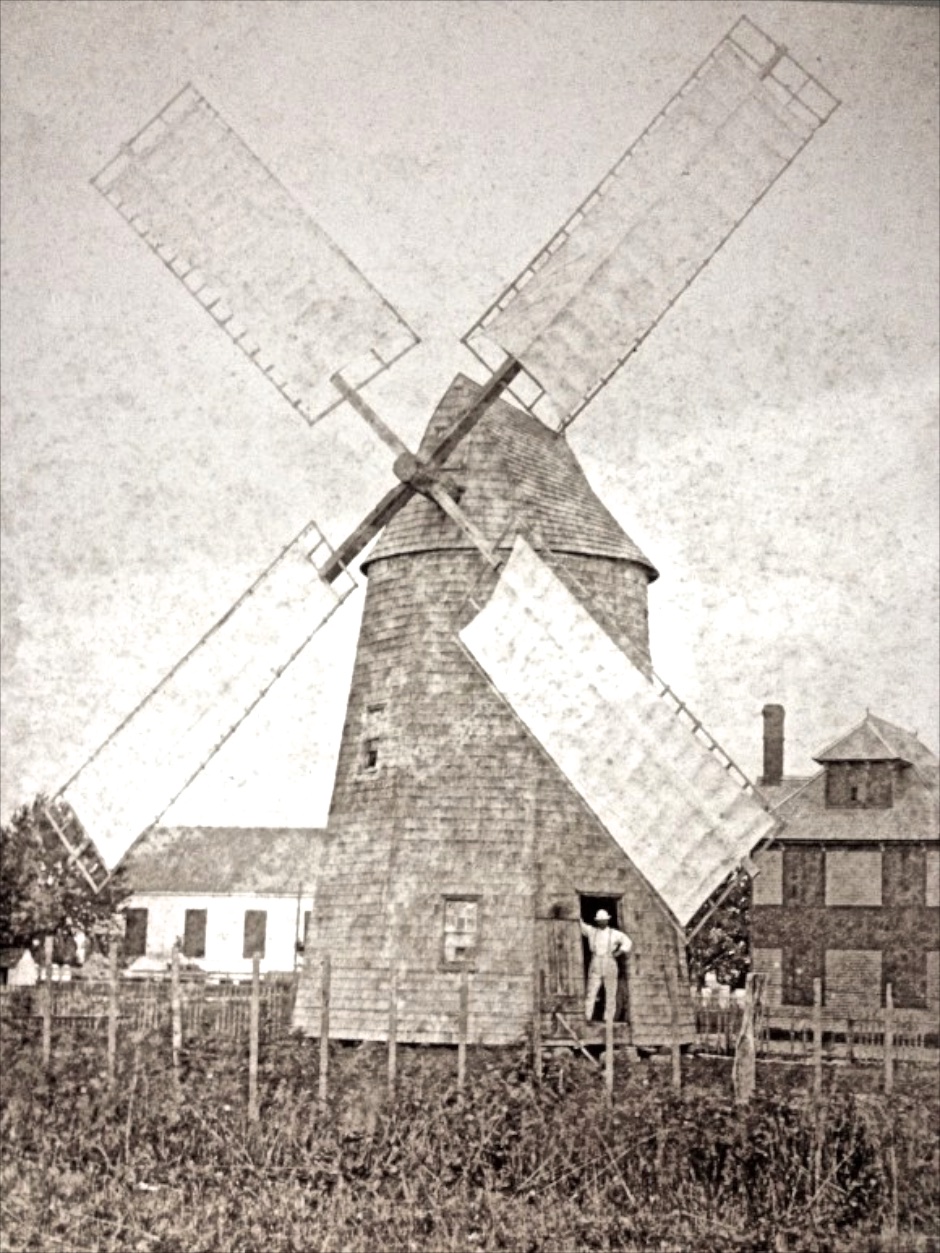

The historic Windmill, in its former location in the center of town. Photo courtesy of Sylvester Manor.

The Windmill

While the property was still in private ownership, the iconic Sylvester Manor windmill was the only Manor structure in full public view. Built in Southold c. 1810 by Nathaniel Dominy, an East Hampton carpenter and millwright of local renown, it is the only surviving windmill from the North Fork and one of the few left on the East End. The invoice Dominy submitted to the Southold millers reveals that the structure was built by hand in 186 days of labor.

In 1840, the mill was brought by barge to Shelter Island and installed near the site of the present school building in the center of town, replacing an older mill that had burned down. Operated by local miller Joseph Congdon until about 1855, it fell into gradual disuse before being purchased by Lillian Horsford in 1879, who wanted to see the old mill preserved and appreciated. Though owned by the Horsfords, the mill remained in the center of town for several decades more, and was even put back into service grinding meal and flour during a brief period of World War I food conservation initiatives.

It was not until 1926 that Cornelia Horsford had the mill moved to Sylvester Manor, where it has since presided from a rise in the 4-acre field overlooking Manwaring Road. The Windmill Field is the highest natural point on the property and was the first field returned to active agriculture by the Sylvester Manor Educational Farm.

Courtesy of Sylvester Manor (image cropped). Frances Benjamin Johnson Collection, Library of Congress.

Courtesy of Sylvester Manor (image cropped). Frances Benjamin Johnson Collection, Library of Congress.

The Gardens at Sylvester Manor

As with the Manor house, the gardens at Sylvester Manor have seen great changes over the centuries as dictated by evolving tastes and needs. The garden planted by the Sylvesters in the 1650s would have included vegetables and herbs, and records show that an orchard of fruit trees was laid out at the NE corner of the current garden site. Though ornamentals would not have been a priority at a site so raw, remote and dedicated to commercial food production, Grissell Brinley Sylvester is credited with bringing cuttings with her from England in 1653 and establishing the first boxwood in America at the Manor. Several generations of Sylvester descendants have used box prominently in their garden redesigns, while other family members took cuttings home and spread new generations of Manor boxwood across Long Island and New England.

The current 2-acre garden is what remains of Cornelia Horsford’s grand 1908 reshaping of the property as a Colonial Revival showpiece. Over the 18th century axial plans laid out by Brinley Sylvester, who had planted the gardens for esthetic and commercial use, Cornelia cut back and transplanted the box hedges, built terraced and parterre flower beds, and, perhaps in homage of the Sylvester’s Amsterdam origins, included a sunken Dutch flower bed, accessed by a graceful staircase descending from the rose garden. In the NE corner of the former rose garden still stands the 18th century privy (or outhouse), painted the same soft yellow as the house, and paneled inside with wainscot removed from the Ladies parlor during a late 19th-century remodeling.

By 1950, Alice Hench was already a passionate gardener at her family’s Dering Harbor property when she met Andrew Fiske, and came to humorously credit their marriage on a shared love of tending plants: “Mr. Fiske came to visit one weekend and said, ‘You have some very fine boxwoods. Why don’t you bring them to Sylvester Manor?’ By Monday, we were engaged.” Thus Alice Fiske began a long and famous tenure as mistress of the manor gardens, often driving the tractor herself. She indelibly left her own mark on the Manor gardens with massive plantings of her signature daffodils and well-tended roses, while faithfully caring for the beds laid out by Cornelia in 1908.

————————————-

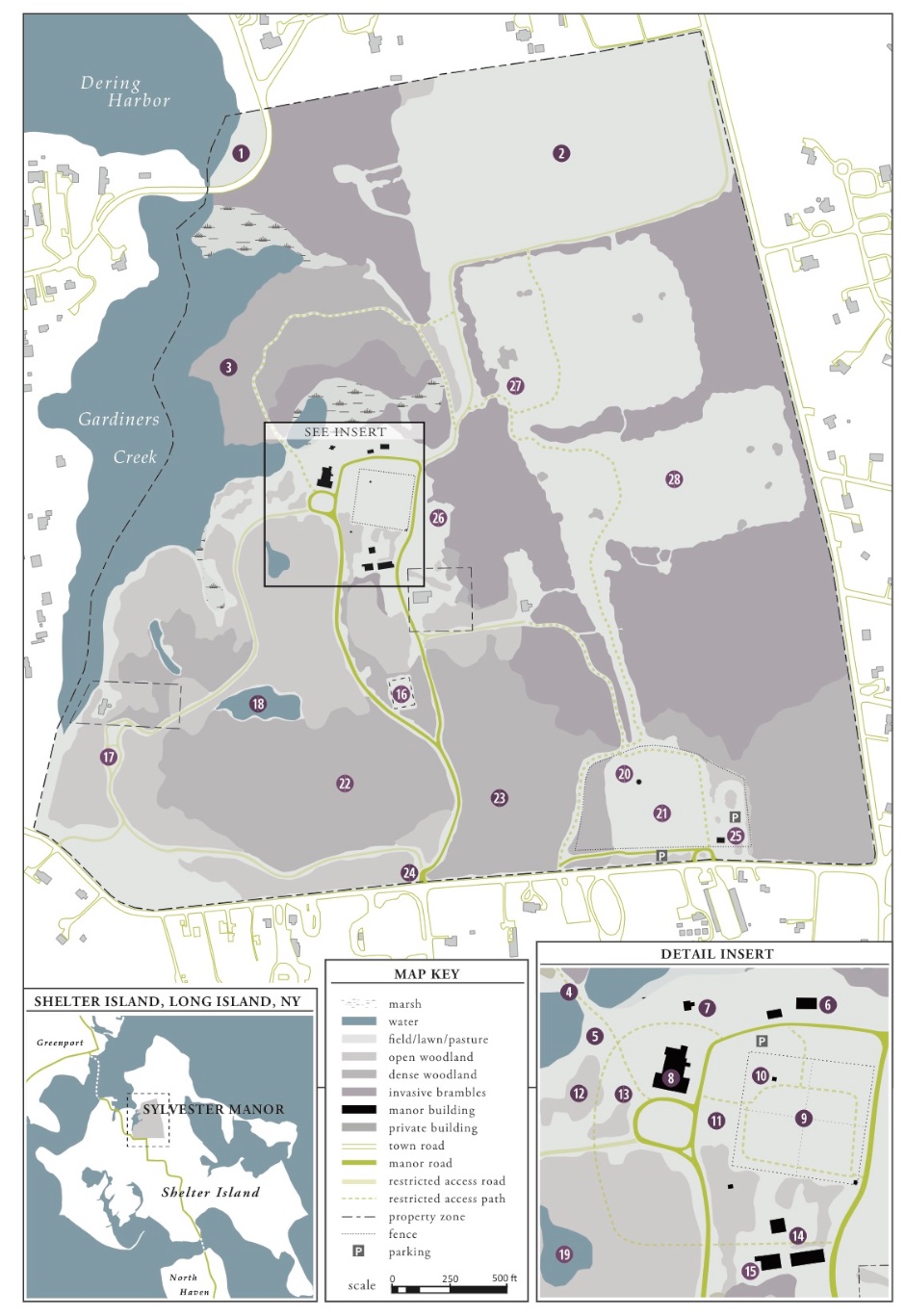

MAP OF SYLVESTER MANOR

Please call for access hours. Stay on paths. Do not litter. No pets except for service dogs. No smoking or open flames. Do not disturb wildlife or landscape.

Please call for access hours. Stay on paths. Do not litter. No pets except for service dogs. No smoking or open flames. Do not disturb wildlife or landscape.

1 — Dering Harbor Beach is named for Thomas Dering, Manor Proprietor from 1752 to 1785 who figured in the Revolutionary War. In the 1600s, European ships anchored off the beach, and row boats ferried supplies to and from the Manor’s core.

2 — At 26-acres, the Big Field has offered an agricultural vista for centuries and is a remnant of a much larger farm. It was preserved through the sale of development rights in 2012, protecting over 83 acres of productive farmland including this field and the Old Fields to the south, see 14 below.

3 — Native Manhansett tribespeople maintained a small village on Manhansett Neck after Nathaniel Sylvester arrived in 1652 on lands inhabited for millennia. In 2009, Sylvester Manor owner Eben Ostby donated a permanent conservation easement on 22 creekfront acres to Peconic Land Trust.

4 — The Land Bridge was reconstructed around 1909 on the site of a former 17th-century tide-powered sawmill spanning a neck of Gardiners Creek.

5 — Goods brought over in ships from the Netherlands, England and Barbados were transferred ashore by rowboat at the Historic Water Landing. Grain, barrel staves, salt, meat, and livestock were shipped out around the Atlantic, to local ports, the Caribbean, and Europe.

6 — The Engine Barn is home to tractors, chainsaws, mowers, leaf-blowers and the like.

7 — The Furnace House, believed to be an 18th century building, was once home to Eben Norton Horsford’s summer chemistry studio.

8 — The 1737 Manor House was built by Brinley Sylvester (1694-1752) to serve as his home and the symbolic center of Shelter Island. Designed in the new Early Georgian style of Newport, Rhode Island, the house replaced the original 1652 Manor House, a First Period building with a red tile roof. A Historic Structure Report completed in 2013 confirms that beams from the original Manor House were repurposed in the 1737 attic.

9 — The Historic Garden, linked to Brinley Sylvester’s time, features a long axial path off the SE corner of the house. The garden was divided into sections for fruit trees, vegetables, flowers and shrubs. The original beds were redeveloped as tastes and needs changed, most notably by Cornelia Horsford and Alice Fiske. Volunteer efforts to revive the garden are underway.

10 — The 18th Century Privy in the garden is a four-seater outhouse with one tot-sized training seat. Gardeners may have used “humanure” from the privy for compost.

Boxwood at Pathway. From the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Devision. Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952, photographer

Boxwood at Pathway. From the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Devision. Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952, photographer

11 — Tradition has it that Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester brought the first boxwoods to America. The Boxwoods on the lawn may be scions of the original specimens, and can be traced back at least to the late 18th century.

12 — The enormous Copper Beech on the back lawn was a gift to the Manor from Asa Gray in the mid-1800s. Gray, called “the father of American botany,” wrote the first standard textbook on the subject and introduced Darwin’s theory of evolution to this nation. Please do not climb on this very old and fragile tree.

13 — The 17th-century English maritime Cannon was unearthed by landscapers in the 1950s. It was buried, according to legend, to hide the manor’s British ties from Dutch soldiers who circled the house in 1674 during the 3rd Anglo-Dutch War.

14 — The Long Barn and Small Barn contain the Manor’s woodshop, field office, tool storage supply depot and storage space. This area has been the center of our working farm for over 100 years.

15 — Originally used as a milking parlor for heritage cattle, the Benjamin Glover Barn shelters our collection of old farm tools, vehicles, and furniture.

16 — The “Burying Ground of the Colored People of Sylvester Manor since 1651”, so commemorated in 1884 by the Horsford family, reportedly contains the remains of as many as 200 Native Americans and enslaved Africans and their descendents. Sacred ground, the plot is fenced but no gravestones exist, and the identities of those buried here are not known. In 2013, archaeologists conducting ground penetrating radar surveys confirmed multiple burials at the site.

17 — The Quaker Cemetery Monument commemorates the role Nathaniel Sylvester, one of the earliest Quaker converts, played in sheltering early Friends from the Puritan persecutions in the 1650s. Present-day Friends now hold Meetings here weekly in spring, summer and fall. The adjacent Creek Cottage is a private residence, built in the 1740s to house the Island’s first minister.

18 — Pepperidge Pond is named for the tall Nyssa Sylvatica trees growing on its south bank.

19 — Daffodil Pond is spring-fed and was probably used to water Nathaniel Sylvester’s livestock. Each spring, the south-facing bank sprouts in thousands of daffodils.

The Windmill at Sylvester Manor. Photo courtesy of Sylvester Manor.

The Windmill at Sylvester Manor. Photo courtesy of Sylvester Manor.

———————-

Restoration in Progress / Photo 2021

20 — The 1810 Dominy Windmill was used to grind wheat into flour for over 100 years. Built on the North Fork of Long Island, it was brought by barge and ox-team to the center of Shelter Island in the mid 1800’s. It was last used to grind flour during food shortages in World Wars I and II.

21 — The Windmill Field is home to our market garden. Over 80 vegetable varieties are grown here, and are sold at our farmstand, to restaurants, and to our Community Supported Agriculture subscribers, who help fund the farm early in the season and share the bounty that unfolds.

22 — The Pine Forest was planted around 1900, at a time when it was believed that pines scrubbed the air and were therefore a remedy for tuberculosis.

23 — The Oak Forest, a mixed hardwood forest of mostly second-growth trees, is the largest woodland at the Manor and runs from the Quaker Cemetery all the way to the Windmill Field. Stands of white and red oaks attracted Nathaniel Sylvester to Shelter Island for their utility in crafting the barrels so indispensable to his partners in the West Indies, used to ship sugar, rum, and molasses.

24 — The 1915 Manor Gates greet visitors from the center of town. Designed in Colonial Revival style by landscape engineer James Greenleaf, they provide a grand approach to the winding drive that ends at the front door of the Manor House.

25 — The Farmstand was built in 2011 using lightning-struck pines milled on the property. Its mortise and tenon timber frame echoes technologies employed in the Windmill and Manor House. In 2013, the Farmstand was enclosed and expanded in response to growing needs, using trees felled by Superstorm Sandy.

26 — Our Greenhouse is a simple way to mitigate our climate in winter and spring. We start our seedlings here — over 100,000 per year.

27 — The Watermelon Patch is, we believe, one of the oldest continuously cultivated fields at the Manor.

28 — Work continues in our Oldfields area in an effort to revive historic farmland, saving it from the choke of invasive vines. In early 2013, 44 acres of historic farmland were cleared and are being returned to active agriculture, offering exciting new possibilities for pasture restoration, cultivation and archaeological study.

—————————————————————————————————

SYLVESTER MANOR

80 NORTH FERRY ROAD, SHELTER ISLAND

PLEASE CALL 631.749.0626 TO PLAN YOUR VISIT

For further information: farm/CSA, Programs, Special Events, Workshops & more…

Visit WWW.SYLVESTERMANOR.ORG

Copy, map & archival images courtesy of Sylvester Manor

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Support Us This Season

SYLVESTER MANOR GIVES TO THE COMMUNITY IN SO MANY WAYS:

• By growing a local food system and young farmers

• By sharing a remarkably intact historic site

• By offering stellar bluegrass and Shakespeare performances

• By inviting all through these gates to make their own connections to story and place

Sylvester Manor Educational Farm greatly needs and sincerely appreciates your generous support!

—————————————

The Internal Revenue Services has designated Sylvester Manor Educational Farm, Inc. a 501c (3) organization. Your contribution is fully tax-deductible to the extent permitted by law.

Financial and other information about the Sylvester Manor Farm’s purpose, programs, activities and the latest report filed with the NY Attorney General can be obtained by contacting Hilary McDonald at Sylvester Manor, P.O. Box 2029, Shelter Island, NY 11964 or upon request, from the Attorney General Charities Bureau, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

________________________________________________________