History of Southold

A Brief Account of Southold’s History

by Antonia Booth

Southold’s official flag proclaims it the oldest English town in New York State. Founded in 1640 by Puritans from the New Haven Colony, Southold celebrated its 350th birthday in 1990 and the town will have 375 candles on its cake in 2015.

The many histories of Long Island written in the nineteenth century focus mainly on Southold’s first one hundred years. Despite continued emphasis by historians and genealogists on the town’s colonial beginnings, Southold’s long history includes change as well as continuity, transformation as well as tradition and innovation along with inflexibility.

In his influential1845 book on Long Island the Reverend Nathaniel Prime says without equivocation, “Southold was the first town settled on Long Island”. Southampton only began disputing Southold’s primacy in 1878. (from the July 1878 issue of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society’s publication, The Record, Vol. IX, No. 3, p.148.)

Established patterns of seventeenth century migration dictated that men would come first from England in order to assess the dangers and possibilities of the New World and to prepare the way for women and children. Those who went ahead usually possessed special skills like the carpenter, Richard Jackson, who built a house in Arshamomoque early in 1640. By the time the Reverend John Youngs, “organized his church anew” and left New Haven with his followers in October of 1640, it is highly probable that the men of the group had been in Southold for some time, preparing shelter and planting crops for the hard winter ahead.

When Reverend Youngs and his congregation arrived in Southold (at the spot that would be dedicated as Founders Landing in 1915), the adventurous Richard Jackson was ready to move on and had sold his land, “his dwelling house and all appurtenances” to another early settler, mariner Thomas Weatherly.

When Reverend Youngs and his congregation arrived in Southold (at the spot that would be dedicated as Founders Landing in 1915), the adventurous Richard Jackson was ready to move on and had sold his land, “his dwelling house and all appurtenances” to another early settler, mariner Thomas Weatherly.

Well before 1640, title to all the land from what is now Orient Point to Wading River was bought by New Haven’s magistrates from the Corchaug Indians. Youngs and his Adherents moved onto land already cleared by the Corchaugs, whose name for the area was Yennecott.

The main settlement of the new colony was laid out, beginning from the Town Creek, in four acre lots. A church organized in congregational style was established on the northeast corner of the present cemetery of the First Church of Southold. The wealthiest of the heads of family who accompanied Reverend Youngs was the baker, Barnabas Horton. William Wells was lawyer for the group and Thomas Mapes was their surveyor. The settlers brought in the famous (infamous?) Indian fighter, John Underhill, to live in the center of the community at Feather Hill. Fortunately, the Corchaugs were few in number, peace loving and helpful so Underhill’s services were not needed for long.

The main settlement of the new colony was laid out, beginning from the Town Creek, in four acre lots. A church organized in congregational style was established on the northeast corner of the present cemetery of the First Church of Southold. The wealthiest of the heads of family who accompanied Reverend Youngs was the baker, Barnabas Horton. William Wells was lawyer for the group and Thomas Mapes was their surveyor. The settlers brought in the famous (infamous?) Indian fighter, John Underhill, to live in the center of the community at Feather Hill. Fortunately, the Corchaugs were few in number, peace loving and helpful so Underhill’s services were not needed for long.

The church built in 1640 served the colonists in Southold not only for religious services but was also the center of town government and its arsenal. Each freeman from 16 to 60 was responsible for his own gun and ammunition, for militia service, and for standing watch over the community. Fines were imposed for dereliction of duty and for disobedience. The colonists were so mindful of possible attack that the church contained a gun rack in which worshipers could store their guns during services.

There were only a few specialists and very little division of labor among the first settlers. The newcomers brought livestock with them and, soon, herds of cattle could be found penned up on common land. Sheep, goats and swine had to compete with wolves and wildcats for existence. As more fields were cleared they were planted to crops. Wheat, corn, and rye were supplemented by garden patches where women tended potatoes, parsnips, carrots and melons. At this transitional time, sharing much of the work and responsibility with men, women came close to equality with men.

Most of the early historians of Long Island were clergymen. Universally, they lauded the first settlers as “healthy, thrifty, moral, prudent and frugal”. Southold was unusual among early towns on the Island in its particularly close union of church and state, its harsh exclusionary practices and the fact that it adopted the Mosaic Code ( the Ten Commandments) as town law. Temporal and religious authority was vested in the church and only white freemen who were also full church members could take an active part in governing. Southolders took pains to ensure that only those with like beliefs would become part of the community. (In 1657, when Quaker Humphrey Norton criticized Rev. Youngs in church, he was fined ten pounds, severely whipped, branded with the letter “H” (for heretic) on one hand and banished from Southold.) The colony lost many of its original settlers who moved on to other parts of Long Island. However, others soon took their place and brought an increase in total numbers.

Population pressures necessitated changes. A new and larger church was built in 1684 on the site of the present Town Hall. The colonists dug a dungeon under the original meeting house and used it as a jail for the entire county from 1684 until 1725. (Suffolk County, which then extended all the way to Queens, was established in 1683). Crimes punishable by death were far fewer here than in England, but the ultimate penalty could still be invoked for bearing false witness, for forgery and arson, for denying the authority of the King, and, “against children for smiting a parent.” Lesser crimes were punished by whipping or ducking under water. Alcohol was a factor in many of these cases. Drinking was almost universal and the colonists brought with them not only tools, clothes and arms, but also plenty of “aquavitae”,( “water of life”), and brewed their own hard cider and beer.

Population pressures necessitated changes. A new and larger church was built in 1684 on the site of the present Town Hall. The colonists dug a dungeon under the original meeting house and used it as a jail for the entire county from 1684 until 1725. (Suffolk County, which then extended all the way to Queens, was established in 1683). Crimes punishable by death were far fewer here than in England, but the ultimate penalty could still be invoked for bearing false witness, for forgery and arson, for denying the authority of the King, and, “against children for smiting a parent.” Lesser crimes were punished by whipping or ducking under water. Alcohol was a factor in many of these cases. Drinking was almost universal and the colonists brought with them not only tools, clothes and arms, but also plenty of “aquavitae”,( “water of life”), and brewed their own hard cider and beer.

Population increase also led to a demand for more land. Surveyor Thomas Mapes laid out the section known as Calves Neck, between Town and Jockey Creeks, and the tract was divided among the freemen for use as common pasturage. Three large divisions of land were made in 1661 at Oyster Ponds, Corchaug, and Occabauk. The last consisted of all the land from Mattituck Creek to Wading River and ran from Peconic River to the Sound, which in those days was called the North Sea. These three great divisions marked the beginning of the settlements of Orient, Mattituck, Cutchogue and Aquebogue. Arshamomoque, although, the first part of the colony settled, did not formally become part of Southold Town until February 1662. Hog Neck (Bayview) was divided for pasturage among 66 owners in 1702. The last of the common lands to be divided were South Harbor and Indian Necks.

The Indians who formerly occupied these lands were pushed out. A number were enslaved. In 1698, for example, James Pearsall of Southold, sold to John Parker of Southampton an eight year old Indian girl named Sarah, “daughter of one Dorkas, an Indian woman”. Sarah, described by Pearsall as “my slave for her lifetime,” brought the sum of sixteen pounds, becoming the property of Parker and his heirs “during her natural life”. Many Corchaugs died of diseases contracted from the white settlers and many others intermarried later with black slaves whose children became the property of Southolders.

The Indians who formerly occupied these lands were pushed out. A number were enslaved. In 1698, for example, James Pearsall of Southold, sold to John Parker of Southampton an eight year old Indian girl named Sarah, “daughter of one Dorkas, an Indian woman”. Sarah, described by Pearsall as “my slave for her lifetime,” brought the sum of sixteen pounds, becoming the property of Parker and his heirs “during her natural life”. Many Corchaugs died of diseases contracted from the white settlers and many others intermarried later with black slaves whose children became the property of Southolders.

Each household at first raised only enough crops for its own use but, with more land available and trade with New England and the West Indies growing, flax and tobacco farming became profitable. Before the existence of a market economy, every household wove its own fabric and fashioned its own clothes.

Civil War in England between Crown and Commonwealth from 1642 until 1649 obstructed communication between the North American settlements and the mother country. The seven year hiatus also weakened ties between England and her American colonies. Virtually all Puritans were sympathetic to the cause of the Commonwealth and few regretted the beheading of King Charles the first. Under a Protectorate England was without a King for a time but soon after King Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, he gave Long Island to his brother, James, the Duke of York.

Reluctantly, Southolders severed their ties with Connecticut and in 1664 they became subjects of the Duke. They were issued a new patent, or land grant, from the Duke’s agent in America , Edmund Andros. Confirmed in their ownership of all the land from Plum Island to Wading River, Southold was obliged to pay to the Duke’s agent “one fatt lamb” annually. Soon after, the Dutch stronghold New Amsterdam was renamed New York in honor of the Duke and Suffolk County became part of the “East Riding of Yorkshire”.

The new English administration ordered every boat sailing out of Southold harbor to clear at the port of New York. Since much local trade was with New England, this inconvenience added to the dissatisfaction Southolders already felt at having to accept the New York charter. As subjects of the King, 150 Southold men were sent to Ticonderoga after 1754 to fight in the French and Indian War, known also as the Seven Years War. Their commanding officers were British and there was much resentment at the cruel treatment the troops received from them. Reeves, Tuthills, Terrys, Pennys, Overtons, Howells, Hortons, Beebes and Booths were among those who felt the lash of the English officers from 1754 until 1763. Another of the Southold men serving was Benjamin L’Hommedieu. His son, Ezra L’Hommedieu, along with fellow students at Yale University, Thomas Wickham and Jared Landon, would become leading patriots when Southold and other colonies were finally ready for independence from Britain.

There were no newspapers in Southold during the eighteenth century. The population at the beginning of the Revolution was just over 3000, excluding slaves. Townspeople got their news from Connecticut papers, from travelers, or from returning mariners. Taverns were the center of social life as well as of information. George Washington visited Booth’s Inn in Greenport in 1757, long before the Revolution, and later, Moore’s Tavern in Southold was host to Dr. Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin.

Because the annual town meeting continued to be held at Southold, that hamlet kept its primacy over the newer settlements. At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, Southold contained fifteen taverns and an even larger number of retailers licensed to sell spirits. Spirits were sold by the gallon and Freegift Wells of Hog Neck was but one of many who bought rum by the hogshead and divided it among his neighbors. John Peck, whose tavern stood where the Southold Free Library is now, was both a tavern keeper and a retailer of alcoholic beverages. The culture became so secular that the principal diversions of male Southolders were horse racing, cockfighting, card playing and shooting at the mark.

In 1776, although many Southolders remained loyal to the Crown almost half fled to Connecticut. It became known that the British were sending an occupying force to Southold to requisition produce and livestock for the British army in New York and to force colonists to take an oath of allegiance to the King.

Soon, entire families, with their crops, livestock, furniture and household goods departed from Mattituck Creek, Goldsmith’s Inlet in Peconic, or Petty’s Bight in Orient. The difficulties endured by Southolders were complicated by an epidemic of cholera and dysentery which killed many. More men than women left Southold and in some cases the wives of rebels were left behind to protect their homesteads. The colonists placed a good deal of trust in the British policy of not occupying houses tenanted by their owners. From 1776 until the war ended in 1783, the British occupied Southold with about 500 infantry and 50 cavalry, off and on, for a total of seven. years. The seat of government was transferred to Mattituck, so that the Redcoats and their Hessian mercenaries could more easily control the town.

The British closed churches, plundered horses and grain and even dug up gold and silver buried by those who left to fight against the English. Trees were cut down for fuel to keep British officers in New York warm throughout the long occupation. When patriot funds ran out in New England, those who had left for the mainland lived in poverty while those who stayed behind suffered even more. Many Southold militia men fought in the Battle of Long Island, after which their units disbanded. Some went on to fight in New England. In 1777, Lt. Col. Return Jonathan Meigs, with 170 Americans of the Continental Army, led his troops across Southold for a daring and successful raid on British ships at Sag Harbor. They returned to Connecticut across Long Island Sound with 90 prisoners. Later that year, sailors from a British ship in Peconic Bay engaged in a skirmish on land with members of the Cutchogue militia. There was some loss of life to the English. British ships bombarded houses close to the shoreline, especially on Hog Neck.

When England finally evacuated from New York in 1784, many of the refugees of 1776 returned to Southold. They attempted to rebuild their homesteads, replant crops and forests destroyed by the enemy and replace flocks and herds. Many were forced to borrow on their lands. Farms that had been handed down from father to son for more than a hundred years passed to other families.

Decades of penury followed. Cash was always scarce in Southold, but the years after the Revolution were particularly hard. Not long after the end of the war the Rev. Dr. Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College, toured Long Island and pronounced that, because of the Island’s insular position, its “people must be always narrow and contracted in their views, affections, and pursuits”.

War with Great Britain in 1812 had little direct effect on Southold, or for that matter, on Suffolk County. A blockade was in effect along the coast but ships were able to slip through. An English fleet occupied Gardiners Bay and from that vantage point was able to attack American ships. Foraging parties could and did set from the English mother ships to loot barns and homes on the mainland. Sag Harbor, a leading port of entry, contained an arsenal. In November of 1812, Southold contributed a company of soldiers captained by Gilbert Horton to defend Suffolk County and Col. Benjamin Case of Southold commanded the military post at Sag Harbor.

Still without a newspaper, and before the invention of telephones, radio, television, or, of course, the Internet,eastern Long Islanders were isolated and self-sufficient. Markets were few and distant, reachable only after a rough trip in small vessels. A New York State Gazetteer of 1824 describes Southold’s houses as “principally old, without paint and very poor”. The population was a little less than at the beginning of the Revolution, and included one “foreigner” and 28 free blacks and eleven slaves. ( Slavery in New York State was outlawed in 1827.) The entry on Southold concludes, “The present inhabitants retain the manners and customs of their ancestors, with the same reverence for religion, and sober habits; fraud is seldom practiced and a law-suit is almost as rare as an earthquake.”

In this insular world, townspeople found their social life revolving around their churches. Diaries and journals mentioned almost weekly attendance at funerals. In addition, revivals were held for days at a time which did much to increase church membership for the various denominations. Charismatic visiting preachers increased attendance as well. Women quilted, alone or in groups, and went to singing schools, canned, preserved, put up pickles, wallpapered, cared for the young and the sick, prepared the dead for viewing; all in addition to their growing responsibilities as moral guardians of the home.

In the 1820’s, every home in Southold still had a spinning wheel and every hamlet a weaver. Among the farm crops was flax for making their own linen. Farmers sheared their own sheep and when the cattle were ready for market they were bought up by drovers and herded to the western end of Long Island. Many Southolders left for New York and Brooklyn in the hope of earning more money. Greenport incorporated in 1838 and the village rapidly became a whaling center. With the village’s new prosperity the shipping and shipbuilding industries that had been traditionally centered in the hamlet of Southold, were gradually transferred to Greenport. Many men left for California to look for gold.

What truly transformed the Town of Southold was the coming of the railroad in 1844. It was with the goal of improving communication with Boston that the small village of Greenport was chosen as a terminal. Isolation from the rest of the state was ended and distant markets brought close. As land values rose and farming methods modernized, the townspeople prospered. They could afford to buy fabrics rather than weave their own. The struggle for a bare existence was ending. Instead of needing to be a “jack of all trades”, people became specialists. In the new division of labor some went to sea as sailors or whalers while others prospered as tailors, hatters, blacksmiths, coopers or cordwainers (shoemakers). Mails were no longer carried by horseback or stage once a week, but were delivered daily along with passengers from far away. Summer visitors were attracted to the area. Boarding houses flourished and hotels were built in all the hamlets. Orient already had the oldest summer resort on Long Island, the hotel of Jonathan Latham, while the Southold Hotel was an established center of social life. Mattituck had Klein’s Hotel and in Greenport, the Peconic and Wyandank Hotels joined the old Clark House in 1845.

Change came in the religious as well as in the social sphere. By the time the railroad reached Greenport, Cutchogue, Mattituck, Orient and Greenport had long had Presbyterian churches of their own. The Methodist Episcopal church organized in 1794 while Baptists first organized about 1810. The Universalist church was built in 1836. The Roman Catholic church began soon after the railroad arrived along with its mostly Irish laborers. Some German immigrants were Catholic, the rest joined the Lutheran church, first meeting in parishioners’ homes until a Lutheran church was built in 1879. Many of the Italian families who came to work around the end of the century also joined the Catholic Church. Tifereth Israel is one of the oldest synagogues on Long Island. The A.M.E. Zion church was not organized until 1920 although the 1858 Chase map of Greenport shows an “African church” on Broad Street. Episcopal services were first held in a cottage behind the Wyandank Hotel, and Mattituck’s Episcopal church was built in 1878.

No longer was the North Fork without newspapers. The Republican Watchman moved to Greenport from Sag Harbor in 1844 and the Suffolk Times began in the village in 1856. The new era of prosperity brought by the railroad was also evidenced by the founding of the Southold Savings Bank in 1858.

Unfortunately, the prosperity initiated by the railroad did not last. Railway policies were not fiscally sound and the Panic of 1857 and subsequent depression affected Southold as well as the rest of the country. With a population of under 6,000 Southold was largely an agricultural community, with some sectors of the economy involved in shipbuilding, fishing, whaling and commerce. A poor farm of 300 acres was located in the hamlet of Southold, Greenport was the commercial center of the town, Laurel was called Franklinville, and what is now Peconic was known as Hermitage.

Unfortunately, the prosperity initiated by the railroad did not last. Railway policies were not fiscally sound and the Panic of 1857 and subsequent depression affected Southold as well as the rest of the country. With a population of under 6,000 Southold was largely an agricultural community, with some sectors of the economy involved in shipbuilding, fishing, whaling and commerce. A poor farm of 300 acres was located in the hamlet of Southold, Greenport was the commercial center of the town, Laurel was called Franklinville, and what is now Peconic was known as Hermitage.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, or the “War of the Rebellion”, as it was called in the North, Southolders were quick to volunteer. The Southold Hotel was used as an enlistment center. A series of lectures aimed at encouraging enlistment was given in the Southold Presbyterian Church by Stewart L. Woodford, a former assistant U.S. district attorney of New York. Woodford, who had relatives in Southold, resigned his position in order to organize a company of the 127th Regiment of the New York Volunteers on eastern Long Island. No doubt the men who joined were patriotic, but for some the bounties and monthly allowances (eight dollars a month to the volunteer’s wife and two dollars a month for children under eleven) voted by the Town of Southold must have been an incentive to enlist. In addition, the Town voted to pay up to $400. per substitute for those who did not wish to serve themselves. One hundred and twenty men enlisted from Southold in 1862. Three of these men were born in Ireland, four in Germany and one in England.

The 127th Regiment, in which most Southolders served, moved around often but did not see much action. They did fight at Honey Hill and Mackay’s Point, South Carolina. Other Southold men fought with the 163rd, the 165th, the 170th and the 176th New York State Volunteers. Three Southolders were killed in action, twelve discharged with disabilities, two died as prisoners, twelve more died of disease and 78 were mustered out with their companies.

The two local newspapers had opposing loyalties. The Suffolk Times supported the war effort but the Republican Watchman was a Copperhead paper. Its editor was arrested and jailed for his Southern sympathies. In general, the community of Southold supported its soldiers with rallies and the raising of “Liberty Poles”. The Ladies Aid Society of Mattituck sent bedding and clothes. The Town of Southold spent over $50,000. on the war and its debt was not paid off until 1871. In honor of its soldiers, the Ladies Monumental Union erected a statue at Budd’s Park in Southold which bears the names of all in the hamlet who fought.

Southold suffered from the usual post-war depression but by the 1880’s the visitors first brought by the railroad regularly filled boarding houses and hotels in each hamlet as soon as the temperature rose in June. Six steamers also connected Greenport to New York City, New London, Connecticut, Newport, Rhode Island and Block Island in the summer and brought tourists back and forth. As whaling died out, other industries connected with the water grew and prospered. Menhaden fisheries, the scallop industry, fertilizer plants and oystering provided good livings and made the name of eastern Long Island well known in city markets. In the 1890’s Greenport alone had twenty large fishing smacks taking huge quantities of cod in winter and bluefish in the summer from the waters off Long Island and New Jersey.

North Fork roads had been improving since the Civil War but it was the introduction of the safety bicycle with pneumatic tires that marked a turning point in the quality of the highways. A “Liberty Bill” was passed in the New York State Legislature in 1887 giving bicyclists the right to use the highways. The money collected for bicycle licenses was used to construct bike paths all over Suffolk County. On the North Fork, a continuous path ran from Greenport to Riverhead, presaging the fine roads that would be built with the coming of the automobile.

As people began to enjoy more leisure, the age of sport was inaugurated. Southold had a long history of horse racing, but in the nineteenth century large horse farms were maintained on the North Fork. The woods and streams attracted scores of hunters and fishermen. Country estates were built in the early twentieth century along the Sound bluff. For those who could not afford to buy a second home, the beaches attracted picnickers and bathers traveling at first by rail and then later by automobile.

In addition, religious groups built campgrounds where families enjoyed their vacations in a “moral and refined” atmosphere. Later, boys and girls’ camps were added. It became clear that a hospital was badly needed and in 1905 a Hospital Association was organized. The Eastern Long Island Hospital opened in 1907 and its first patient was Mr. F.S. Butler who had been working on the building and cut his head on a rusty nail. Realizing that added numbers of visitors were straining its resources and that more beaches and parks were needed, Southold formed a Board of Parks Commissioners. The Ladies Village Improvement Society had a memorial gateway constructed at Founders Landing in 1915 and presented the park to the Commissioners.

This increase in summer visitors did not alter the fact that Southold was primarily an agricultural community. While many Yankee owners of the original farms had sold to the Irish and moved away in search of better jobs, the majority of Southold’s land was still planted to potatoes, cauliflower and sprouts. In turn, Irish families would move on in the early twentieth century in search of a better living after selling their farms to new immigrants from Poland, Russia and Lithuania.

While these changes were taking place in Southold in the second decade of the twentieth century, war was declared in April of 1917. Quickly, rallies were held and Home Guards organized in Greenport, Southold and Mattituck. About three hundred men and women from Southold served in the armed forces. Reflecting the growing diversity of Southold Town they were no longer just Yankees, but Black, Irish, German, Greek, Polish, Italian, Lithuanian, French, Portuguese and Puerto Rican. Mrs. Lillian Cook Townsend organized over 800 workers for the Red Cross. Mattituck had a branch of the Red Cross as did Cutchogue-New Suffolk, Laurel, Peconic, East Marion and Orient. Typical of the dedication of all the members, Mrs. Eunice Fanning, over seventy years of age, knitted 13 pairs of socks monthly for the duration of the War. Fishers Island, which became a part of Southold Town in 1879, had its own branch of the Red Cross made up both of both permanent island residents and summer visitors.

While these changes were taking place in Southold in the second decade of the twentieth century, war was declared in April of 1917. Quickly, rallies were held and Home Guards organized in Greenport, Southold and Mattituck. About three hundred men and women from Southold served in the armed forces. Reflecting the growing diversity of Southold Town they were no longer just Yankees, but Black, Irish, German, Greek, Polish, Italian, Lithuanian, French, Portuguese and Puerto Rican. Mrs. Lillian Cook Townsend organized over 800 workers for the Red Cross. Mattituck had a branch of the Red Cross as did Cutchogue-New Suffolk, Laurel, Peconic, East Marion and Orient. Typical of the dedication of all the members, Mrs. Eunice Fanning, over seventy years of age, knitted 13 pairs of socks monthly for the duration of the War. Fishers Island, which became a part of Southold Town in 1879, had its own branch of the Red Cross made up both of both permanent island residents and summer visitors.

Quickly, better jobs were available on the North Fork. The Greenport Basin and Construction Company began building submarine chasers for the war effort where workers received forty cents an hour. Uneasy at being identified with the enemy, the village government changed the name of Germania Street in Greenport to Fourth Street. Among the local men seriously wounded in the “war to end all wars”, were Pasquale Santacroce of Greenport; born in Italy but now an American citizen. George E. Hannibal, a Black and also from Greenport, received from the French government the Croix de Guerre, after being seriously wounded in the Argonne Forest.

Peace brought with it another economic downturn as well as votes for women on the plus side and, on the negative, the secret society called the Ku Klux Klan whose activities on the East End were aimed against Catholics, Jews and Blacks. Prohibition of liquor by the federal government was followed by the private and illegal enterprise of rum-running. In order to monitor violations of the Volstead Act, a Coast Guard station was established in Greenport but many local people made pin- money unloading illegal liquor from fast boats. As the hatred promulgated by the Ku Klux Klan gradually subsided, The Greenport Watchman was sold to the former editor of Klan Kraft, Rev. Howard Mather.

The good times accompanying shipbuilding and rum-running eventually yielded to another depression which followed the Crash of 1929. Many local schools and roads still in use in Southold Town were built by the WPA during this difficult period. A bright spot in 1934 was our capturing of the America Cup in the series of races off Newport. Aboard the American defender, “Rainbow” were three Southolders, Captain George Monsell and crew members Harry Klefve, Sr. and Harry Klefve, Jr.

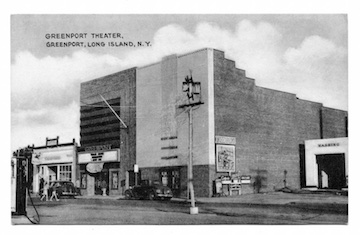

Distracting attention from the hard times of the 1930’s, at least for a while, was the tropical hurricane that swept eastern Long Island in 1938. As a result of the 100-mile an hour. storm, over 600 trees were uprooted, lives were lost and many houses and businesses were demolished. In 1939, a new theatre replaced the old Greenport Theatre destroyed by the hurricane. Two years later, in 1940, Southold Town proudly celebrated its 300th anniversary.

Prosperity did not return to Southold Town until World War II commenced. Even before America became involved, The Greenport Basin and Construction Company was enlarged and began to build mine sweepers. Civil Defense units were organized and, after war was declared, blood donor programs began and Red Cross activities renewed. Many farmers and defense workers received deferments because their work was vital. However, other local men and women served with all branches of the service. The first Suffolk resident to lose his life was Russell Penney of Mattituck, killed in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Another Mattituck man who died was killed on Leyte Island. He was Wojciech J. Majcher, born in Poland but an American citizen when he died for his new country.

The end of World War II was another turning point in Southold Town’s development. Relative prosperity, improved transportation and communication, combined with almost universal ownership of automobiles, combined to increase the number of second homes on eastern Long Island. People from New Jersey, New York City, Brooklyn, Nassau and Queens Counties began spending summers on the North Fork. In 1940, Southold’s year-round population was just over 12,000. Soon, magazine articles were touting Southold as an ideal and inexpensive place for retirement. Publicity of this sort attracted enough people to the area so that, by the 1960’s, Southold Town had the highest median age in New York State.

While the total numbers of people living within the town were going up, so were the demands of the federal, state and county governments on smaller municipalities. Mandates, without compensatory funding, raised standards of health and safety. Departments already in existence, such as the Assessors Department, The Highway Department and the Police Department, had ever greater demands upon their resources each year.

Court cases increased, recreation and human services programs were initiated. Applications to the building department multiplied and threats of litigation over development added to the workload of the Zoning Board of Appeals. A Community Development officer was hired in 1981 to look for federal and state grants, expanding to public works, while a full-time planner came to the town in 1987. Presently Southold Town maintains a busy planning department and planning board as well as a department of land preservation. A Information Technolgies department maintains electronic links between Southold government’s scattered campuses: town hall, an annex, the police and highway departments, the recreation and human resources centers, the transfer station and the former Peconic School.

As old methods of farming became financially unattractive; land was kept open and green with horse farms, nurseries and vineyards. Solid waste management and planning for the future have replaced cholera epidemics and bands of roving wolves as preoccupations of present day Southold citizens. The problem of the next fifty years will be to satisfy the ever increasing demands of the public while preserving the quality of life, the natural beauty, and the serenity that today’s residents regard as the heritage handed down to them by the men and women who came here to establish Southold in 1640.

———————————

History of Southold courtesy of Antonia Booth, Town Historian, Southold, New York

www.southoldtownny.gov

———————————–

Photo identifications in order of presentation:

— Long Island Sound from Horton Point Lighthouse

— Founders Landing, Terry Lane at Hobart Road, Southold

— Beach at Founders Landing Park, Southold

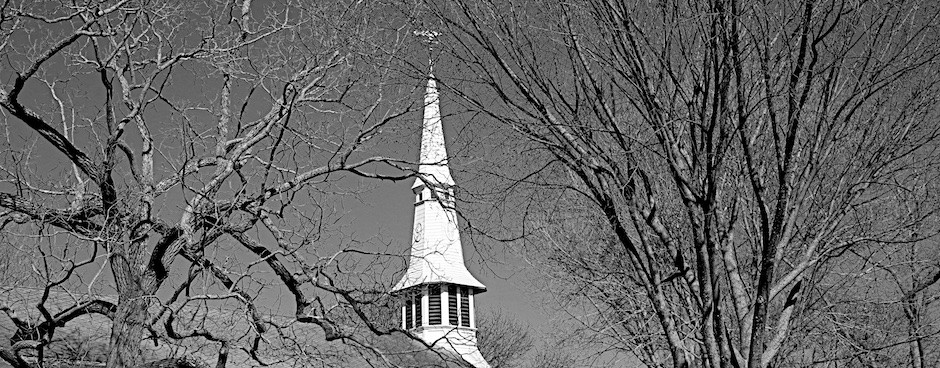

— Steeple, Presbyterian Church, Cutchogue

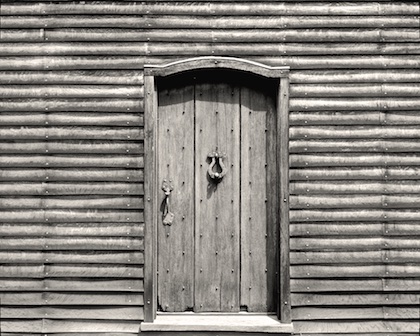

— Front Door, Old House, Cutchogue, 1649: National Historic Landmark

— Fort Corchaug Archeological Site, National Historic Landmark, Cutchogue at Downs Creek

— Front Door, Thomas Moore House, circa 1750, Southold Historical Society & Museums, Southold

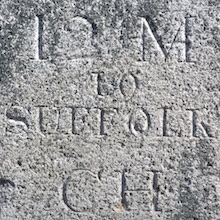

— Mile Marker, Cutchogue

— Barn, Sound Avenue, Mattituck

— Horton Point Lighthouse, Southold. Built 1787. Commissioned in 1790 by George Washington

— World War Memorial, Greenport

— Second World War Memorial, Greenport

— Greenport Theater, archival postcard, courtesy of Eric Woodward

— Long Island Sound at Horton’s Point, Southold

———————–

Photos copyright Jeff Heatley.

__________________________________________________________