Plein Air Painting, Archival Photograph.

The Art Village

Shinnecock Hills, 1891

To walk down the narrow lanes in the enclave known as the Art Village is to be transported back in time to a place where intimate, miniature scale and tactile ambiance convey a richness that has nothing to do with wealth. From the plantings to the street gutters to the garden gates and enchanted cottages, the Art Village is a magical world unto itself. And it is no wonder that the effects of this inspired place can still be felt in American art and architecture more than a century later.

Art Village with Windmill, Archival Photograph.

Art Village with Windmill, Archival Photograph.

In 1891 the Shinnecock Summer School of Art, the first out-of-doors art school in the United States, opened to allow amateur and professional art students from all over the country to study plein air painting under the tutelage of artist William Merritt Chase. The 100 to 150 who studied there each summer boarded at the Art Club, which accommodated 30 women with a chaperone; local boardinghouses; with fishermen or farmers; or in one of the dozen cottages constructed in the Art Village compound.

At the behest of Mrs. William Hoyt—the daughter of Lincoln’s secretary of the treasury, Salmon Chase, later a Supreme Court justice—and Mrs. Henry Kirke Porter, Samuel Parrish donated the land for the school. On February 2, 1891 a New York World article reported that prominent individuals such as “Mrs. Astor, Mrs. August Belmont, Mrs. Andrew Carnegie, Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt, Mrs. Ballard Smith and Mrs. Whitney” were also supporters of the school.

The choice of location for the Art Village, just beyond the western edge of Southampton Village at the flat end of Shinnecock Hills, was explained by a student: “The existence of the school there is due primarily to the fact that some rich people owned some poor land.” In 1878, Ernest Ingersoll wrote in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine that “Shinnecock Hills is a synonym of what is utterly barren and useless . . . sandy knolls densely grown with a chaparral of scrub oak and pine, alternating with swampy hollows where the moss trails far down from the skeletons of dead trees, and the imagination conjures dreadful inhabitants out of the dark tussocks.”

It was on this barren, exposed landscape near the Shinnecock Indian Reservation that the Art Village cottages, grouped near the studio building, appeared like diamonds in the rough. What makes this collection of buildings so unique has to do with the layout of curving and angled streets, the interrelationships of these tiny residences to one another and the street front, and the avoidance of architectural statement-making. Lack of regularity, dictated by the irregular shape of the site itself, gives the complex an expansive feeling and a sense of anticipation that can come only from wondering what lies around the bend.

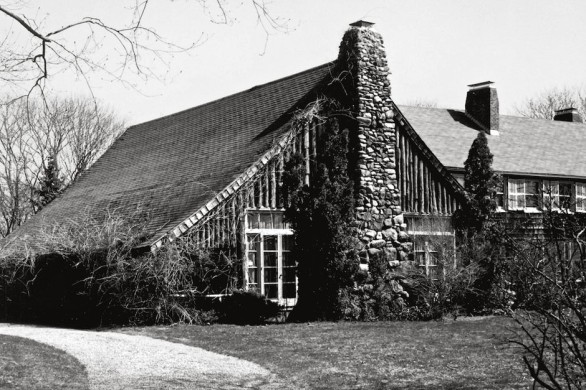

Art Village Cottage, Photograph 2007.

Art Village Cottage, Photograph 2007.

The cottage designs, no two alike, adhere to a unifying palette of applied elements such as unpainted shingles, rustic stone chimneys, turreted bays, subsumed porches, and low, sheltering rooflines punctuated by dormers—all characteristic of the rural regional vernacular building tradition. Antoinette de Forest Parsons, in the June 27, 1895, issue of the St. Paul Dispatch, described the cottages: “The outer walls, washed by rains, and polished by the sun, shine like satin. Inside the cottages are finished in wood of a dark tone, and red curtains in the diamond-paned windows, or swaying festoons of vines that clamber up to the roofs against the gray walls make almost the only spots of bright color.” This self-contained subdivision was given its harmonious and cohesive identity by road gutters of cement inlaid with beach stones; primitive wooden fences between the cottages just a few inches high; and hedges with nascent landscaping, small trees called “pre-Raphaelite” by the students for their meager foliage and installed under the careful direction of Mrs. Porter.

Several publications from the era state that prominent architects designed the cottages, and their signature detailing, possibly indicative of authorship, includes the same type of diagonal windowpanes employed in the work of architects Katharine Budd and Grosvenor Atterbury. Unpainted beaded wallboards resemble those seen in the Stanford White design of the Chase Homestead, and some fireplace surrounds with embossed swags uniquely echo the dainty Colonial theme established in The Orchard by McKim, Mead & White.

Art Village student Katharine Budd, who worked on her own cottage there, also remodeled the cottage once belonging to Mrs. Hoyt for the artist Zella de Milhau. De Milhau named her cottage Laffalot, based on the Indian name Chlioata, bestowed on her by the Shinnecocks, which meant “one who laughs a lot.” Budd, also responsible for the expansion to the studio building, fused a former dormitory structure, moved from across the street, to the rustic, vertical-log studio. Dubbed Villa Artistica in Budd’s personal records, the house became the private residence of Mrs. Porter in 1903 after the school closed. Many of the other cottages also had playful names, such as Half-acre, Stepping Stones, and the Pillbox. Architect Grosvenor Atterbury’s first project in the Art Village was the house he designed for himself. In 1908 he moved the house to another site in Shinnecock Hills.

Life at the Art Village consisted of hard work mixed with recreational activities. On Monday mornings, Chase conducted formal criticism in the school studio. Sketches from the previous week were placed on a 12-foot-long two-sided easel, and the students, seated on campstools, listened as more than 200 studies were critiqued in a morning’s session. One student described the critiques:

This was as good as a bull-fight to the cottagers and the loungers from the hotels—the patrons were out in full force to patronize and gave parties at little expense and with great gusto to their friends, inviting all they cared to invite to attend the morning criticisms. Carriages and even motor cars were at the door, the “nobility” with their lorgnettes ready, the students all sitting on little camp-stools before a large revolving easel. While Chase criticized the studies on one side a servant filled the other side with more. Thus it went round and round until hundreds of daubs had met their fate.

Another student remarked, “Isn’t it perfectly heartless for them to come here and ogle through their lorgnettes, and put on the airs of connoisseurs and laugh when Mr. Chase says cutting things. I’d like to kill them all.” Occasionally, Chase had to make it clear to visitors that the criticism session, intended to aid the students, was not a recreational activity.

On Tuesdays, Chase spent the entire day outside with models and criticized the work of his students while they did their plein air sketching. He was revered as a teacher, and his suggestions were tempered to meet both the needs and abilities of the students. Chase offered comments such as

Open your sky more and paint a tree that birds could fly through . . . Try to paint the unusual: never mind if it does not meet the approval of the masses. Always remember that it is the man who paints the unusual who educates the public. I am never so disappointed in a piece of my work as when it meets with the approval of the public. . . . How much light there is in everything out of doors! Look out of a window and note how light the darkest spots in the landscape are when compared with the sash of the window . . . In painting a sandy beach try to imagine that you are walking upon it, and when dealing with a round object try to feel that it is really round . . . It usually takes two to paint a good picture—one to paint and the other to stand by with an ax to kill him before he spoils it.

Aside from “Chase Days” on Mondays and Tuesdays, the students worked independently outdoors on drawings and paintings during the week. Many of the social activities in the Southampton community, including the plays, dances, concerts, and “witch parties,” were organized by the students of the Art Village. The most recognized event involved Chase’s revival of tableaux vivants, in which models, in some cases Chase’s children or pupils, were grouped in a frame as a representation of a famous painting. Among the best known were Mrs. Chase as Dagnan-Bouveret’s “Madonna” and her daughter Helen as Velasquez’s “Infanta.”

William Merritt Chase’s Studio, Photograph 2007.

Work from the Shinnecock Summer School of Art was exhibited in Philadelphia, in Pittsburgh, and at the New York Art School. School alumni included artists Joseph Stella, Howard Chandler Christy, Rockwell Kent, Charles W. Hawthorne, Arthur B. Frost, and Marshall Fry, and architects John Russell Pope, Grosvenor Atterbury, and Katharine Budd.

The Shinnecock Summer School of Art closed its doors when Chase resigned as headmaster after the 1902 season. Despite its brief history, the school gave expression to a distinctly new form of American landscape painting. Other plein air schools, based on the Shinnecock model, opened around the United States in places such as Cape Cod, Massachusetts; Mendota, Minnesota; and, in 1914, Carmel, California, where the Carmel School of Art again had Chase as head teacher.

Most of the buildings in the Art Village today remain relatively unaltered. Often called a toy village, it remains one of the most unique cultural landmarks in Southampton. Preparations are currently being made by the Southampton Landmarks and Historic Districts Board to have the Art Village designated a historic district.

“The Art Village”

Houses of the Hamptons

By Gary Lawrance & Anne Surchin

Courtesy of Acanthus Press

____________________________________________________________________