Mocomanto archival photo courtesy of M. Cummings

Mocomanto archival photo courtesy of M. Cummings

MOCOMANTO: THE JEWEL OF SOUTHAMPTON

Jonathan S. Foster

When we speak of the “Jewel of Southampton,” we mean the house built on Town Pond in 1882 named “Mocomanto” by its owner Mary Louise Holbrook Betts. But what is a ‘jewel’ — what do we mean by ‘jewel’s’ of architecture? The word jewel here is not used to mean only ‘very nice’, or even ‘great’. These kind of words are reserved for ‘l like it’ maybe, or the best example of a style perhaps, such as the best example for the ‘shingle style’. Jewel is not even appropriate for the best work or even “masterpiece” of an architect, such as Grosvenor Atterbury who worked in New York and Southampton around the turn of the century designing tasteful and often magnificent structures for the well to do.

But Jewel? Jewel is reserved for that one of a kind, rare, creation such as the ancient mythical Palace of Minos, that magnificent town on Crete built in the second millennium BC, 4000 years ago, which was so wonderful a place to live that it was remembered through time. A great idea, actually realized to a perfection without necessarily a specific provenance.

It kind of started when Wyllis Betts rode to the end of the line on the LIRR in 1879 or so and saw the village of Southampton and the town pond in the vast fields or “hamps” along the vast ocean shore facing south and had a vision of a peaceful place for himself and his friends in New York. Hamp is the old English word for ‘field’, from the French “champs”. “Hampton” is a town in the hamps. Wyllis’s vision was probably similar to the feeling that the first settlers had in the early 1600’s when they came over from Connecticut to explore the vast island to the south beckoning in the distance. When they arrived on the south side they saw the vast hamps created by the Montaukettes and Shinnecocks for grazing and ease of movement from season to season. In 1879 that view was almost as it was in 1639.

By 1880 Wyllis had purchased about 27 acres between what became Lake Agawam and the Atlantic and was responsible for the development of St. Andrews Dune Church. His sister in law, Louise Holbrook Betts immediately bought 5 acres near the southwest corner of Lake Agawam bordering Wyllis’s land, and commenced to build a summer house on the site. By 1882-83 she was holding fort in her new creation and enjoying her gondola rides between her cottage and the new Dune Church. It was happening pretty fast and the groundwork for what would be de rigueur as life and activities in this new summer world for this group of New Yorkers was being laid out. Louise’s new summer house, so prominent on the new lake, would be its symbol. But where did it come from? Who designed it? Why did it become so prominent?

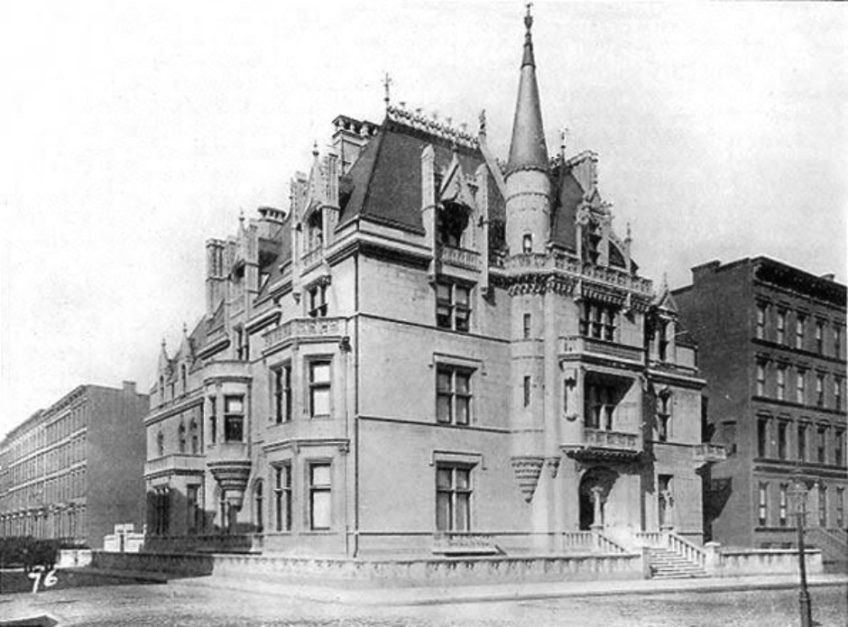

Vanderbilt’s ‘Petit Chateau’, New York City. Richard Morris Hunt, Architect.

The Boston bred Mary Louise Holbrook was 33 in 1880, obviously well traveled and energetic in trying to make her mark in New York as the wife of the prominent patent attorney Fredrick Betts. She was on a mission. She must have watched as the young Alva Vanderbilt at 26 set about to overturn Mrs. Astor as the leader of New York Society by building the grandiose French mansion on the corner of 52nd and 5th. The “Petit Chateau”, as it was known, was designed by the Beaux Arts architect Richard Morris Hunt. It dominated its location with a French chateauesque mixture of castellated detail and a dominant Norman style roof and an exquisite sense of scale. And it was the talk of the town.

Mocomanto operates in a very similar manner. Its Norman style roof dominates the building and is the focal point of the views of and from Lake Agawam. The plan is simple, a 30ft by 40ft rectangle for 2 ½ stories. A fireplace system and chimney was at the center, heating and embellishing the whole. The main floor is for pleasure, dining, reading, and conversation while facing the Atlantic, or the lake through its large windows. One is always aware of the nearness to the wild playground you have chosen to control. The upper 2 floors are for the master suite with similar if not better views and several small bedrooms. The guests and the staff, including the cleaning and kitchen functions were placed in wings off the main core, at the north and the west sides, where there was minimum interest and no views. The house itself was focused on the pleasure and delight of being there. The vast Norman roof structure was articulated at the top third by a step, reinforcing its height, and at the eaves by a series of cutouts above the windows creating a feathery sort of edge giving the roof a floating effect. The East and South sides have a wide piazza surround for the life outside. Mocomanto is scaled for people to enjoy, and to look larger than it was from a distance. It was designed to accentuate the ideal life to the east and south — boating, bathing, conversing in the idyllic world of Lake Agawam. These are the architectural ideas that make up Mocomanto, the dominant roof with its elaborations, a clear hierarchy for use and function zones, a rigorous attention to detail and placement: the sense of life to be experienced in the house and in the views.

The matter of who designed Mocomanto is not clear, but the capable Louise Betts, who brought the gondola from Venice a decade before Thomas Moran famously did in East Hampton, was up to the job of seeing this building get built. Vitruvius, the Roman architect would approve — this has sturdiness, usefulness and delight, the qualities of architecture. It also has more — it has the jewel quality of its manifest ideas. The notion of jewel is clear for Mocomanto. This was the purposely built summer cottage to talk about and strive toward, and when the Southampton colony was written about in places such as the New York Times, Mocomanto and Louise Holbrook Betts were there as the symbols of the Southampton summer scene.

Mocomanto is in danger now from a large expansion that will alter its carefully fashioned scale by mimicking features, adding large extensions and changing its orientation.

This is not a house to be toyed with by playing with its scale or appearance. This is a house to be protected; because by setting so clearly the ideals and goals of this community in such a grand fashion, it became a legend in its own time, and it has continued to be the “Jewel of Southampton.”

— Jonathan S. Foster RA. LEED AP, Architect

________________________________________________________