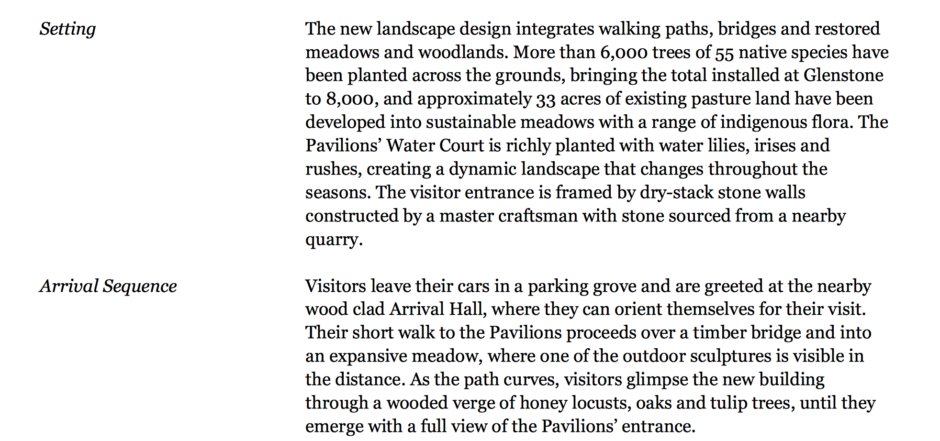

Approach to the Pavilions. Photo: Iwan Baan. Courtesy: Glenstone Museum.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

GLENSTONE

Quotations & Images from conversation — Quiet Architecture,

w/ additional Glenstone museum press copy & images.

——————–

Quiet Architecture: Thomas Phifer and Gabriel Smith in Conversation with architect Maziar Behrooz,

in association with AIA Peconic / Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, on September 15, 2013.

————————————

Pavilions at Glenstone opened / October 4, 2018.

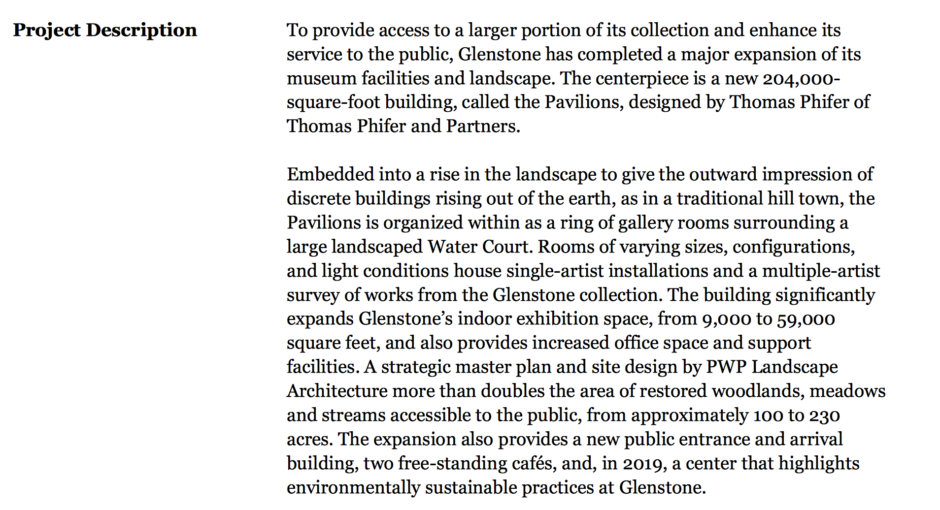

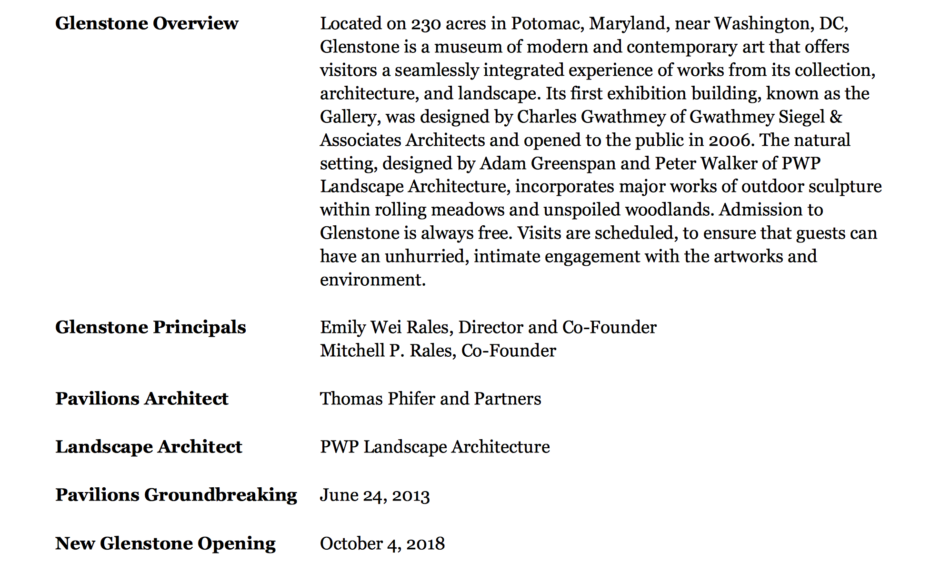

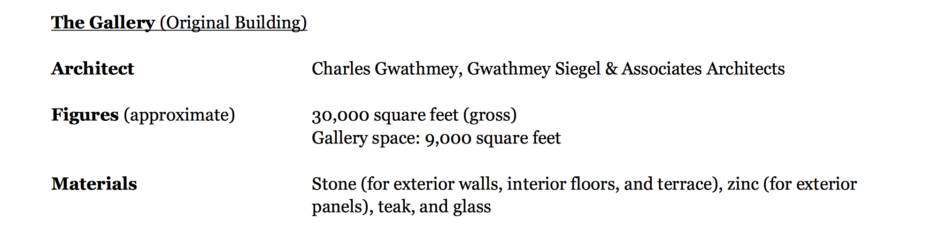

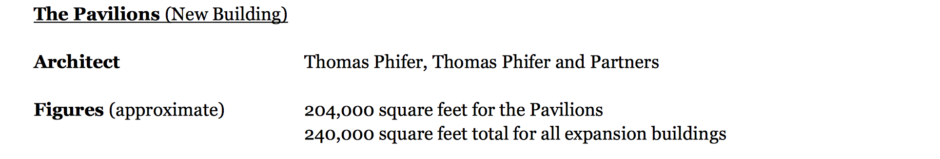

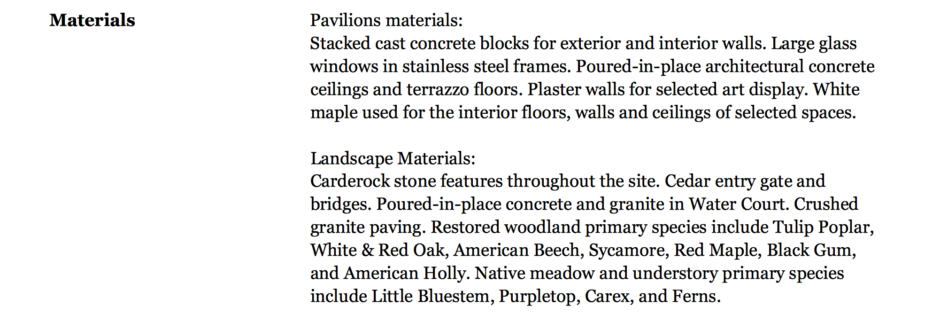

Established by Emily Wei Rales and Mitchell P. Rales, Glenstone opened in 2006 and now includes a new 204,000-square-foot museum building called the Pavilions, designed by Thomas Phifer of Thomas Phifer and Partners; an additional 130 acres of rolling meadows, woodlands, and streams, designed by Adam Greenspan and Peter Walker of PWP Landscape Architecture; an Arrival Hall and bookstore; and two cafés. The original 30,000-square-foot museum building, called the Gallery, was designed by Charles Gwathmey of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects, and opened in a 100-acre setting. With the addition of its new facilities, Glenstone now offers the public a total of 59,000 square feet of indoor exhibition space in two buildings, with all works drawn from its own renowned collection of modern and contemporary art, and 230 acres of serene, unspoiled landscape incorporating installations of major works of outdoor sculpture.

“Mitch and I have been dreaming for years about the day when we’d be able to pull back the curtain and reveal the new Glenstone,” said Emily Rales, director and co-founder of Glenstone. “Now, at last, the art installations and buildings and landscape are complete, and people can finally encounter Glenstone as a whole, as we’ve always meant for it to be seen. We’re excited by Glenstone, and we hope our visitors will share that feeling, now and for many years to come.”

“We’re deeply grateful to everyone who has worked with us to create Glenstone: the great artists who have given us their trust and collaboration, the magnificently talented architects and landscape architects who have been our partners, and the wonderfully dedicated professional staff who have lived this journey with us every step of the way,” said Mitchell P. Rales, co-founder. “Now we’re thrilled to welcome the people who are really the most important collaborators of all: the visitors for whom we’ve built the new Glenstone.”

— Courtesy of Glenstone.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

———- 2013 Conversation ———-

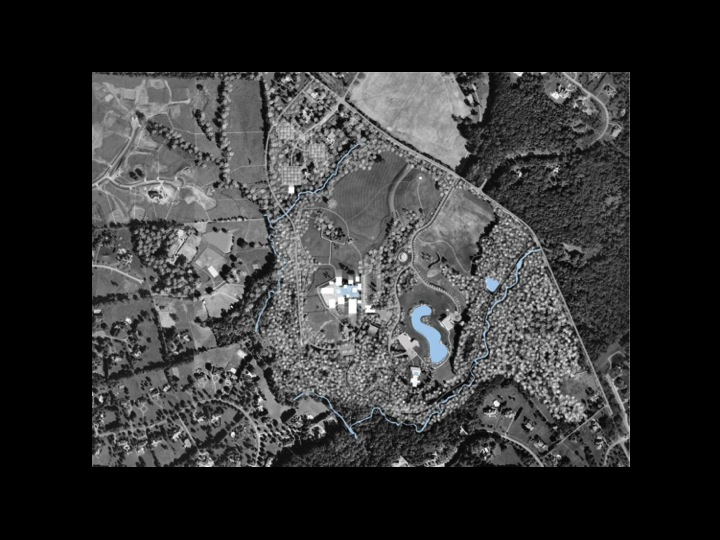

Gabriel Smith: ….This is the site in Potomac, Maryland. It is rolling, horse country, 225 acres, half an hour outside the city [Washington, D.C.].

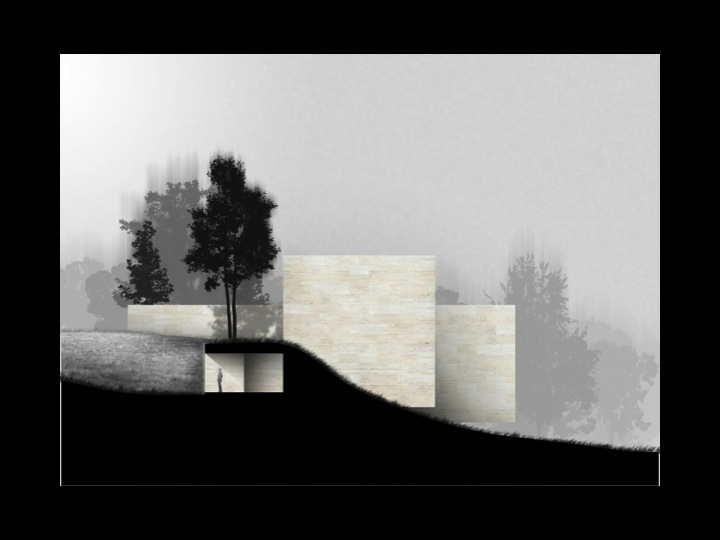

GS: We looked around this site and started noticing that there are these particular locations that kind of come out of this very soft landscape.

Thomas Phifer: This was one of the first images that we made. Actually someone in our office put these together and put a square on it, for some reason, and turned it green.

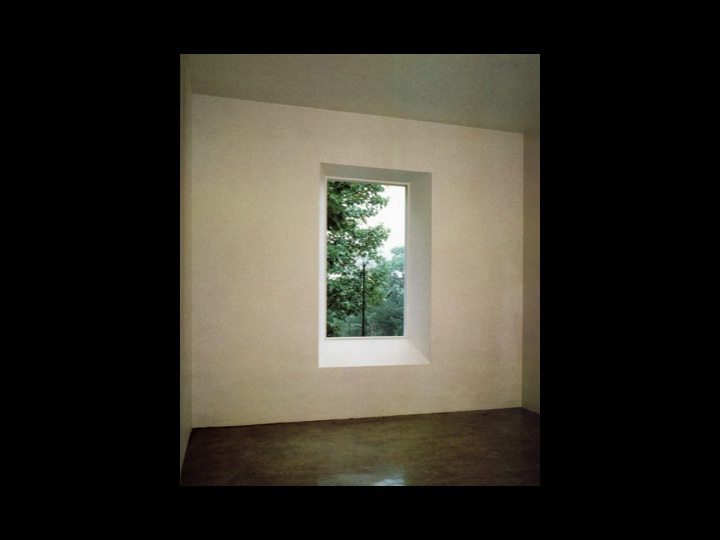

Bob Irwin at La Jolla Museum

TP: It reminded us of this. Bob Irwin was given this room in La Jolla Museum — you could do anything in this room you wanted to do. Bob said that he wanted to cut a hole in the wall. And he battered the wall. And this is the frame view of nature, and this is kind of where the project started.

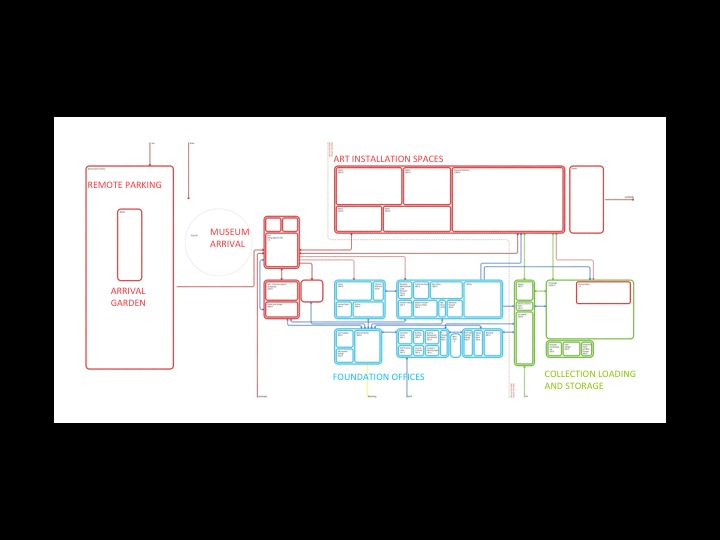

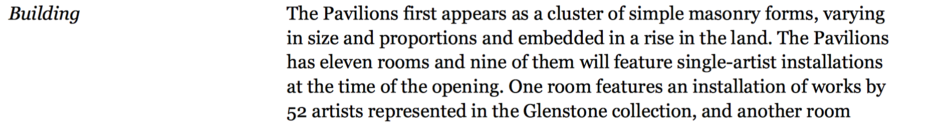

TP: This is the site plan. You arrive and park in the middle. As you walk through the meadow, this is what you encounter. You can see the assemblage of buildings around an existing land form there. We are putting these buildings in this existing land form. And each one of these buildings accommodates a different artist, but it is one artist, except for this larger building, the changing gallery . Every one of of these has either one piece of art or a few works by the same artist.

———- 2018 ———-

Aerial of the Pavilions. Photo: PWP Landscape Architecture. Courtesy: Glenstone Museum.

Aerial View of the Pavilions. Photo: Iwan Baan. Courtesy: Glenstone Museum.

———- 2013 Conversation ———-

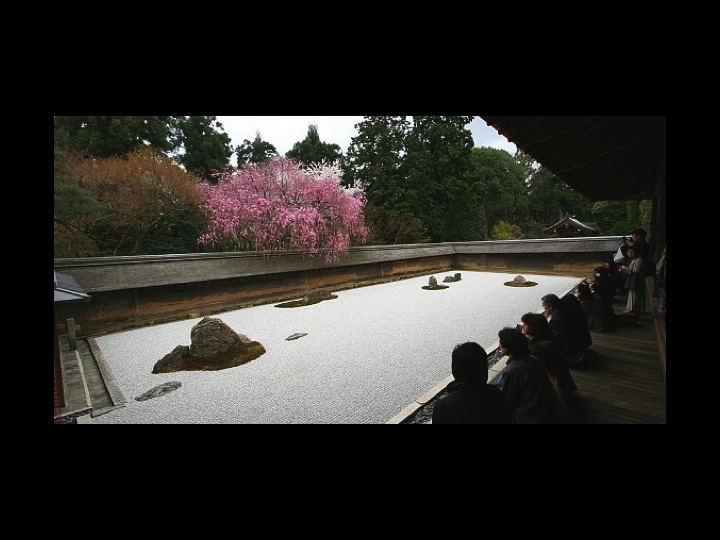

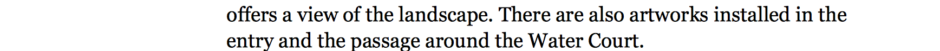

TP: Ryoan-ji is there. It was the inspiration for this planted garden — a place of calm, repose and silence — where all you see is the sky and nature above.

TP: Here there is a planted pool on the scale of Ryoan-ji. And, you come there without the distraction of a bigger landscape. And, you have a sense of calm, or you go [into the museum] and have another experience.

———- 2018 Water Court ———-

Water Court at the Pavilions. Photo: Iwan Baan. Courtesy of Glenstone Museum.

———- 2013 Conversation ———-

Maziar Behrooz: This is a remarkable diagram. It shows how a building that seems seemingly random is, in fact, not. I think there is probably even a grid system that underlies…

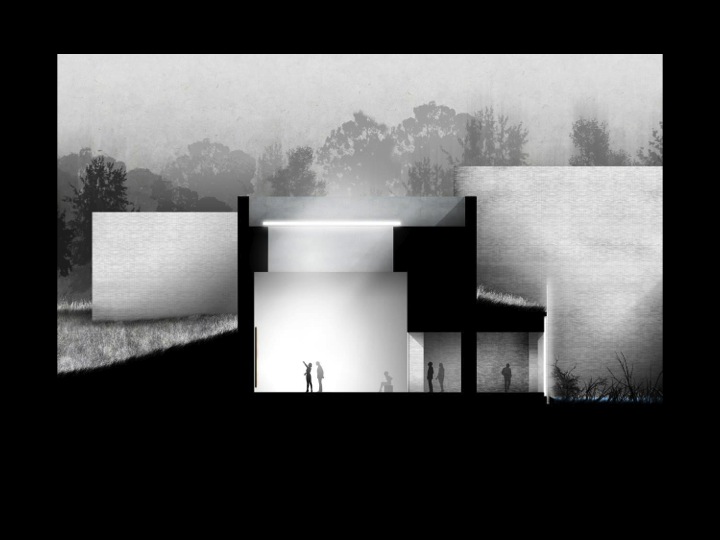

TP: There is a rigorous grid system. There was a lot of study that went in here to understand how you move through passages guided by light and having a slowly unfolding experience.

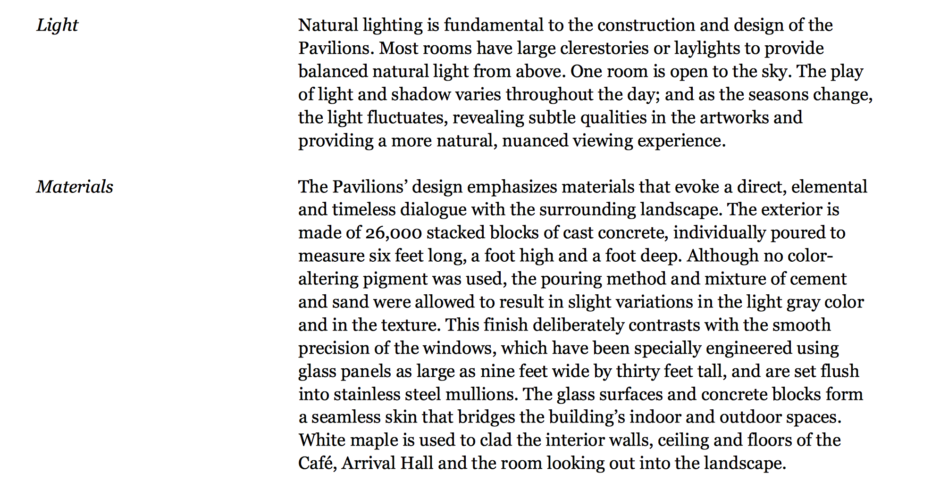

TP: This is Carl Andre, taking something very simple and ordinary and making it special by ordering it.

TP: The whole building is made out of these stacked concrete blocks. 6′ long,1′ high and 1′ deep, and load bearing — in some cases 60′ tall. Made out of absolutely grey cement, with no additives. They get this kind of variety because they are poured over a two year time period, 18,000 blocks, changing humidity, changing temperature, slight change in cement, change slightly in water, bleeding them out — you will get this kind of texture. What we are after here is an authenticity of this material.

MB: Concrete blocks are both inside and outside? And is there insulation between the two layers of blocks?

TP: Yes, there is a concrete wall, there is an air space, and the blocks that stack up on the outside and the inside. But inside the art spaces, those are plaster. You can see what is beginning to happen here — the way you move around corners guided by light. A kind of shifting of buildings starting to happen initially, because we wanted this kind of unfolding experience as you move around.

Audience: Do you have to exit one building to get into another?

TP: No, it is enclosed. There is an enclosed passage that you walk through and look out at the pool.

———- Exterior of Pavilions 2018 ———-

Pavilions at Glenstone Museum. Photo: Jeff Heatley, December 29, 2018.

Michael Heizer, Compression Line, 1968/2016 A588 steel. 75 x 10 x 91⁄2 feet (2286 x 305 x 288 cm) Photo: Jeff Heatley, December 29, 2018.

———- 2013 Conversation ———-

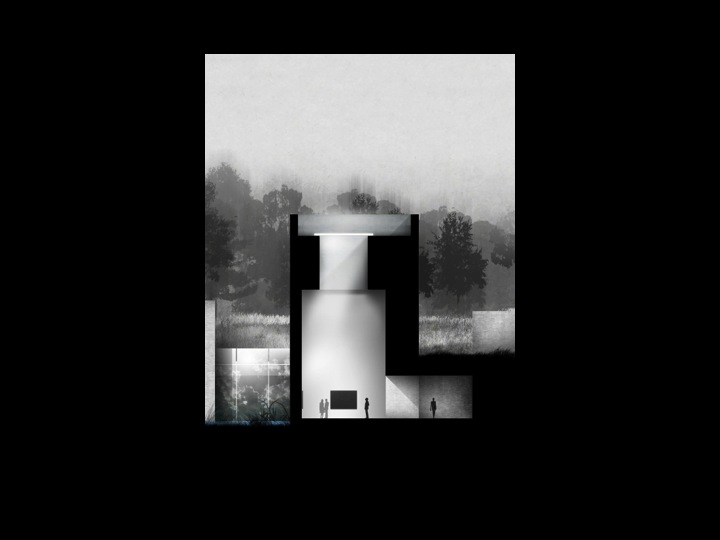

TP: One of the things that we love to do is to be very, very close to our clients. I think this building represents their spirit here — it is a private foundation, run by a husband and wife, founded by them. I think their spirit guided us — they’re quiet, they’re very thoughtful people. I think that quietness and that silence began to influence the kind of experience that we wanted to have here. I think there was that wonderfully symbiotic relationship between architect and the people who wanted to build. This is as much theirs as ours. This was one of the first drawings we made before we did much of anything. These very simple, almost Renaissance cubic light spaces, where we just cut a hole in the ceiling to let light in. We wanted these kind of Roman spaces — kind of simple, heavy architecture to set out on the landscape.

MB: The way the spaces are top lit, of course, continues what you had done in the past, but, in the solidity of the walls, the materials used, it is quite a departure. When they came to you, were they expecting to see lots of transparency and glass and reflectivity that you had explored in previous projects?

Martin Heizer’s North, East, South, West

TP: I think they might have expected that. It is a little hard to know. Very quickly, I think, we were there with something that was heavy and very much about the experience. We focused for the longest time on what the architecture was — the experience of the architecture and the experience of daylight. And the works themselves, and the artists that these buildings were going to contain. Those came together long before the character of the architecture. It was works like this — Michael Heizer’s North, East, South, West — this was our model for the ceilings in the building. It was kind of just this void for light.

MP: In your office, I saw large scale models of the rooms. I think you did those to study the quality of light.

TP: We did that to study the quality of light, the scale of the space, the materiality. All of that. Each room has a different character. It has a different light character, different size and proportion to the works.

GS: It is about fitting those pieces. We really did start from this dialogue about the works. For us, it was very clear — the artwork is extremely powerful and often very hard to understand. And, you have got to clear your mind between each piece. That was something that came very quickly and resulted in a different kind of response.

TP: It’s hard to work on a museum like this without thinking about the Louisiana Museum in Denmark, where the buildings are spread apart, but you go from experience, to a view of the garden, to a passage and then another experience. You get glimpses of the landscape. And I think that building in particular, although it doesn’t look anything like that, the idea that you have an experience, then take a pause, a kind of metabolic change there, a kind of rhythm, a kind of musical rhythm. We also looked at spaces like Ryoan-ji and Japanese temples — having that kind of silence. And, we talked about this with our clients. This was a very cooperative and supportive relationship.

GS: There are thousands of renderings and hundreds and hundreds of technical overlays between this building and the Louisiana building. We took a trip with our clients, but we also — in the finding of this building — we studied. I have never, ever been in an office where it is such a rigorous attitude. This is Tom, really, an attitude about how to work, and it’s just relentless.

TP: I think what we were trying to find — is that silence. You know Lou Kahn talked about silence and light. The kind of silence you find in experience — I think that kind of attitude was extremely important to us. But that, I think, came as a hint from our clients, who have that kind of silence there. And, you counter that with these exuberant works — the Panda and the Rat — this contemporary art — it is kind of heavy. We were trying to find a counter to that, so that there is a silence in the architecture, and, supporting that, are these extraordinary works of our time.

Panda & the Rat –– Rat and Bear by Peter Fischli & David Weiss

GS: They also asked us to make a building that would last for one hundred years. In this day and age — that kind of conversation I have never had with a client. When they began to say what would it take to make this building last one hundred years, the conversations changed. They go toward a different place. And, it’s a combination of the art being hard to understand and also a building that goes beyond a formal exercise or a technologically simple answer — as much as anything that rooting and grounding the project. And, so you keep going back and asking, formally and tectonically, how do we make this thing that is going to be here for a long, long time? And, what does it mean to make a move in that very, very delicate terrain of one hundred years?

Audience: What is that artwork?

TP: This is Michael Heizer — who doesn’t learn something from him?

A: Is there an existing museum on that property now?

TP: There’s a museum that was designed by Charles Gwathmey (Gallery, 2006 — see below). It is on the other side of this big stand of trees. This project sits in a huge open field.

Audience: Was James Turrell an influence at all? They look like Skyspace.

TP: I think James Turrell started when he just cut a hole in the ceiling. He got a little frustrated, and he didn’t know what to do, and he cut a hole in the ceiling of a building, and light came in. It is like the Pantheon. That is the way you feel in Rome — you walk into an old building there, and there is just a hole in the ceiling, and you watch the light. When we were in Rome, we were there almost every day. The Pantheon — we were just mesmerized by the way the light and nature come in and make a work of architecture.

MB: When this building is finished, it will become a big attraction. You will see huge crowds going through it, and I wonder how you project that through this space that has a sense of austerity and richness, at the same time, and a quiet…

GS: This client is extremely disciplined. They have thought about alot of this. When they came to us and said we love this and want to do it, they also had already figured out how to do the ticketing. They are incredible people. They have thought about a lot of things. They are now building a staff, interviewing each person on that staff. They have a mission statement, and it includes a rich marriage between the landscape, the architecture and the art. And they will never, ever, give up on that.

TP: They only want about 20 to 30 people inside the building at one time.Very, very quiet. We removed the books and we removed the cafe from the building. The only thing in this little cluster, in the little village of buildings, are the works — it is all about the works. This is a kind of living testament to their devotion to this silence.

TP: These were some of the early, early renderings we made about this experience in the passage as you move around, kind of guided by light. These were made when we were shifting the buildings around and trying to gauge this kind of notion of how you approach this passage into these rooms.

———- 2018 Installations ———-

Big Phrygian, 2010–2014. Painted red cedar, 58 x 40 x 76 inches (147 x 101 x 193 cm). © Martin Puryear, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Courtesy of Glenstone.

Martin Puryear’s (b. 1941) extensive sculptural practice embraces the global traditions and cultural histories of woodworking. Influenced by his time studying in Sierra Leone and Stockholm, Puryear uses labor-intensive methods to explore concepts including identity and oppression. Fashioned out of handcrafted wood and reclaimed parts of a carriage that the artist found in a barn in France, The Load, 2012 contains a massive sphere resembling a human eye. Sited nearby is Big Phrygian, 2010–2014, a monumental sculpture of a “liberty cap,” a symbol of resistance that appeared in both the American and French Revolutions. These works overlook the water court platform which features a bench designed by Puryear in collaboration with master furniture maker Michael Hurwitz.

—–

Moss Sutra with the Seasons, 2010–2015. Courtesy of Glenstone.

The five-panel painting Moss Sutra with the Seasons, 2010–2015, brings together signature stylistic elements bookending Brice Marden’s (b. 1938) career: two monochromes with complex, layered palettes flank each side of a large central panel which features fluid, calligraphic gestures against a subtly oscillating ground. Each of these monochromatic panels is inspired by a season, beginning at the left with the yellow of springtime and ending on the right with the blue-black of winter. Other wide-ranging influences on the painting include the artist’s long-standing fascination with moss, a Chinese sutra that the artist came upon by chance, and the form and tone of medieval and Renaissance multipanel altarpieces. This piece was commissioned for Glenstone and is housed in a skylighted space designed in collaboration with the artist.

—–

Ever Is Over All, 1997. Two-channel video with overlapping projections (color, sound with Anders Guggisberg). © Pipilotti Rist. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Swiss visual artist and filmmaker Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962) is known for pioneering short-length, engrossing video artworks and multimedia installations. For many of her iconic projects she assumed the roles of director, producer, composer, and star—together conceiving a practice that reflects her varied interests in human emotion, female sexuality, psychology, music, and her own body. Over and over, her films ask viewers to reconcile the duality, and often conflict, between what they see and how they feel. The surreal and analog Ever Is Over All, 1997, is composed with the intent of relaxing the viewer with playful music while showcasing a shocking yet joyful act of repeated vandalism.

—–

Detail — Livro do Tempo I (Book of Time I), 1961 mixed media on wood. 365 pieces, each 6 ¼ x 6 ¼ x 1 ½ inches (16 x 16 x 4 cm) © Projeto Lygia Pape. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Courtesy of Glenstone.

Brazilian artist Lygia Pape’s (b. 1927, d. 2004) iconic sculpture: Livro do Tempo I (Book of Time I), 1961, is composed of 365 unique geometric tiles, each representing an unassigned day in the calendar year. Each tile begins as an identically sized slab of wood which is then cut, rearranged, reattached, and painted in primary colors. Although all elements of the sculpture are created with the same fundamental material, each tile is embedded with its own sense of individuality. Unbound, the “book” is installed on a single wall, echoing the effect of a mosaic, while upon closer examination each of these hand-crafted blocks reveals the intricate process of its making.

—–

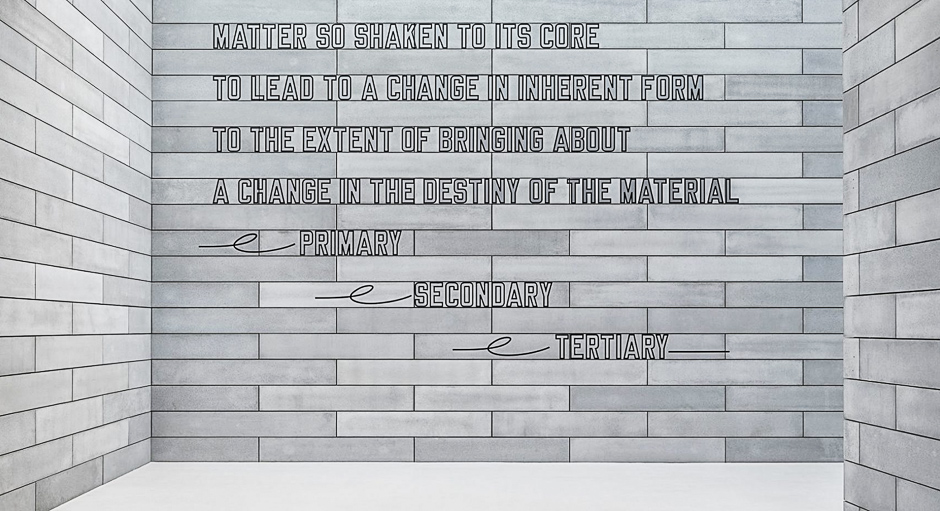

MATTER SO SHAKEN TO ITS CORE / TO LEAD TO A CHANGE IN INHERENT FORM / TO THE EXTENT OF BRINGING ABOUT / A CHANGE IN THE DESTINY OF THE MATERIAL / PRIMARY / SECONDARY

TERTIARY, 2002. Dimensions variable © Lawrence Weiner. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Adapted by Lawrence Weiner (b.1942) for this installation, each line of text of “MATTER SO SHAKEN TO ITS CORE TO LEAD TO A CHANGE IN INHERENT FORM TO THE EXTENT OF BRINGING ABOUT A CHANGE IN THE DESTINY OF THE MATERIAL. PRIMARY SECONDARY TERTIARY,” is scaled to be housed within the height of a single precast concrete block. This statement by the artist could be considered an inquiry, instruction, or even an invitation—asking visitors to consider how matter can shift from one state to another, how and when something is elevated from simple material to “art,” and even, perhaps, how we ourselves are impacted by our own lived experience.

———- 2013 Conversation ———-

GS: You [MB] had asked me to put diagrams in the project slides. We diagram buildings just like everybody else does, but this is really the diagram for us. It’s testing through the visual — these kinds of studies.

Audience: There is no pencil to paper at all? It starts out with those?

TP: I grew up in a generation where I had a t-square, but not any more. We have learned in our office how to work together using the computer. We all sit around the table, we work together, we doodle around. We have tracing paper, but we all work together. None of us sits back there and makes a drawing and tosses it over to the drafting department to get it drawn. It is all done in a very cooperative way — where things are shared.

GS: There is a lot of trust, there is a lot of work, there is a lot of back and forth trust and expectation. There are people who have ideas, who come in the morning and say, what about this?

Audience: How do you budget time for research?

TP: We run a small practice. We have never had over 25 people. We have small teams. That’s the only thing I worry about. We don’t do budgeting. We don’t worry about the little bit of hours happening for each task. We just intuitively do the work.

MB: The day I visited your office you had the whole wall completely covered with really beautiful color renderings of this one project. There must have been at least forty or fifty renderings on the walls and also covering the very large table, as well as study models, small and large.

TP: I think that it is clear, probably through this, that this project is a jumping off point for us. When you realize that this is the jumping off point, I think it’s important to spend the time and effort. We have fees like everyone else. We have budgets like everyone else. All of that stuff exists for this project. This family is self-made, and every dollar that is spent here is carefully analyzed. This is not a budget that jumps off the deep end. We have had to do things here that are very simple. Do things like concrete walks that are about seventy, eighty dollars, a square foot. It is not an extravagant building. It is organized differently, but it is not extravagantly finished.

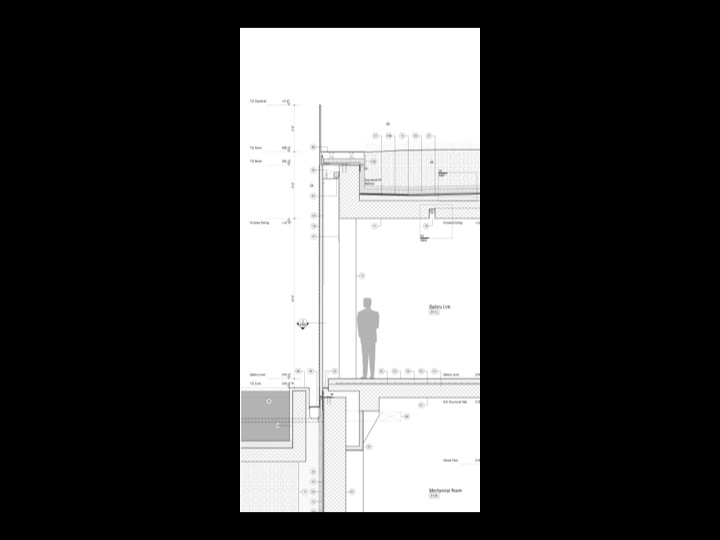

MB: I did ask Gabe to include some details and wall sections.

GS: The concrete block, while it is a very humble, direct material, is up against very, very tall pieces of glass. These pieces of glass are insulated units about 23 feet tall and 9 feet wide. They are very, very large pieces of glass. I think it is the contrast between these enormous pieces of glass that are very, very carefully made and the block that we were chasing for a long time. I think we really came onto something when we found that rich contrast between the high and low.

———- 2018 Installation ———-

Collapse, 1967/2016. A588 steel. 36 x 24 x 16 feet (1097 x 732 x 488 cm). © 2018 Michael Heizer. Photo: Jerry Thompson.

Recognized as a pioneer of the Land Art movement of the 1960’s, Michael Heizer (b. 1944) uses his massive, innovative sculptures to shift our understanding of what art can be. Installed in Room 5, Collapse, 1967/2016 is a large-scale weathering steel sculpture comprised of fifteen beams arranged within—and extending beyond—a box fitted within the surrounding earth. Commissioned for Glenstone, this work is based on a wooden model studying chaos structure that the artist created in 1967. This “outdoor” sculpture is installed within an enclosure open to the elements but accessed only via the Pavilions interior. — Courtesy Glenstone.

—————————- 2013 Conversation —————————-

MB: This is a controlled waterscape.

GS: It actually has different depths for different plant species, so where you have higher plants obviously you have different depths.

MB: Who is your landscape consultant?

GS: Peter Walker.

——————–

———————

Thomas Phifer and Partners

www.thomasphifer.com

———

MB Architecture

www.mbarchitecture.com

———————————————————————-

NEWS APRIL 25, 2019

——–

———- ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER OPENS ———-

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

April 25, 2019 — Glenstone Museum today opened its Environmental Center, including a 7,200-square-foot building that embodies the latest thinking in sustainability, with an opening ceremony. The Center advances the environmental stewardship that is central to the mission of Glenstone, where the landscape has been designed to complement and frame the architecture and artworks, and the architecture has been designed in response to the natural landscape.

The ceremony featured remarks by Emily Rales, Director and Co-Founder, Glenstone Museum; Ben Grumbles, Secretary, Maryland Department of Environmental Protection; Marc Elrich, Montgomery County Executive; and Paul Tukey, Chief Sustainability Officer, Glenstone Museum.

“At Glenstone, we have committed ourselves to protect and nurture the landscape just as we care for our buildings and works of art,” said Emily Rales. “We feel that everyone has an interest in environmental stewardship. Everyone can play a role. That’s why we’re proud to be inaugurating the Environmental Center as an integral, public-facing part of Glenstone, and delighted to welcome friends from the state, the county, and the community who are all making their own vital contributions.”

The Environmental Center facilitates the sustainable practices of Glenstone’s grounds maintenance operations and provides an opportunity for visitors to learn how they can adapt sustainable practices in their own homes and businesses through hands-on presentations and exhibits focusing on some of Glenstone’s efforts, including organic landscaping, composting, recycling, reforestation, management of invasive species, stream restoration, and water management. A few examples of Glenstone’s sustainability efforts include:

· Maintaining its nearly 300 acres of landscape with 100% organic practices

· Planting more than 8,000 trees since 2013

· Restoring more than 9,200 feet of stream bed around the property

· Recycling more than 80% of office waste and food scraps

Glenstone was founded to achieve a seamless integration of art, architecture, and landscape. The Environmental Center brings the public behind the scenes of creating that ideal experience and helps keep Glenstone at the forefront of environmental stewardship.

At the event, Glenstone announced that the Museum will continue to offer guaranteed entry to visitors who arrive by the Montgomery County Ride On bus. The initiative launched as a test in January to encourage visitors to use public transportation and to reduce the museum’s carbon footprint.

Glenstone also received its Montgomery County Green Business recertification, a program designed to encourage businesses and other organizations to take steps that reduce their ecological footprint. The recertification was offered by Marc Elrich.

The Environmental Center will be open Thursdays through Sundays from noon to 4 p.m. and is a self-guided experience. Glenstone associates and experts will also offer regular programming for visitors interested in learning more about sustainability practices.

——————————————

GALLERY

Glenstone Museum

Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects

Opened in 2006, the Gallery is Glenstone’s first museum building and was designed by Charles Gwathmey (1938−2009) of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects.

The Gallery hosts changing exhibitions in generously proportioned spaces and opens up to a terrace overlooking a pond. A limited palette of materials—zinc, granite, stainless steel, and teak—allows the architecture to exist in harmony with the surrounding landscape and the art it houses.

Louise Bourgeois. Destruction of the Father. Photo: Ron Amstutz._Courtesy of Glenstone Museum.

Louise Bourgeois: To Unravel a Torment, on view from May 10, 2018 through January 2020, features five decades of the trailblazing work of the French-born American artist, whose formal innovation and fearless explorations of her own personal history make her an icon of late-20th-century art. Nearly 30 works by Bourgeois (1911–2010), all from the museum’s collection, are on display, including The Destruction of the Father, 1974, a recently acquired masterpiece realized at a pivotal moment in her career. — Courtesy Glenstone.

———————–

Organic Landscaping

Glenstone offers 230 acres of landscape fully integrated with the architecture and art. The landscape includes paths, trails, streams, meadows, forests and outdoor sculptures throughout the grounds.

We have followed an organic approach to landscaping since 2010, working hard to identify gentle alternatives to harsh chemicals in order to maintain a healthy environment for our visitors and native wildlife. We maintain our own composting station and produce compost tea, which we use as a fertilizer and soil amendment throughout the grounds.

The landscape was designed by PWP Landscape Architecture.

Our Environmental Center is a multi-use maintenance and education facility that offers experiential learning. Here, in 2019, you can learn about our efforts in composting, organic landscape management, waste reduction, materials recycling and water conservation—and how to take these practices home with you.

————————-

For further information on Glenstone, please visit www.glenstone.org

Note that reservations are required to visit Glenstone.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

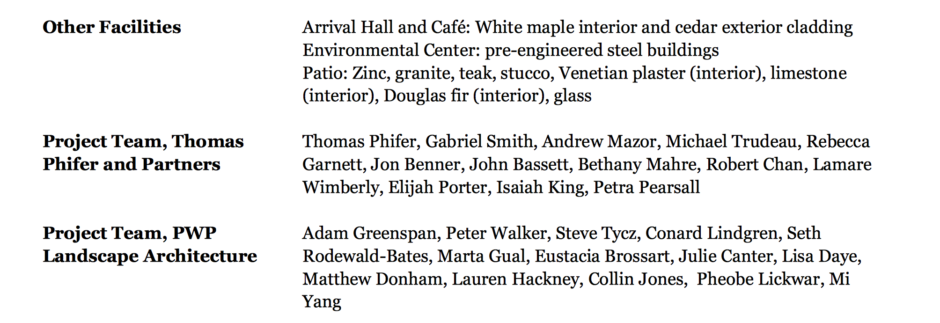

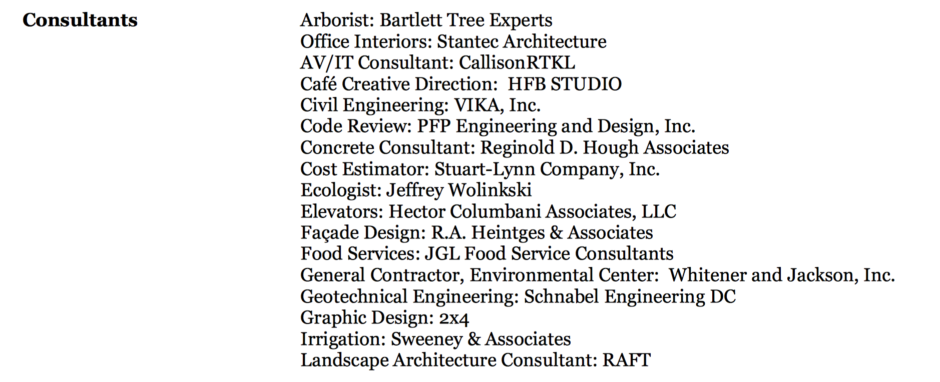

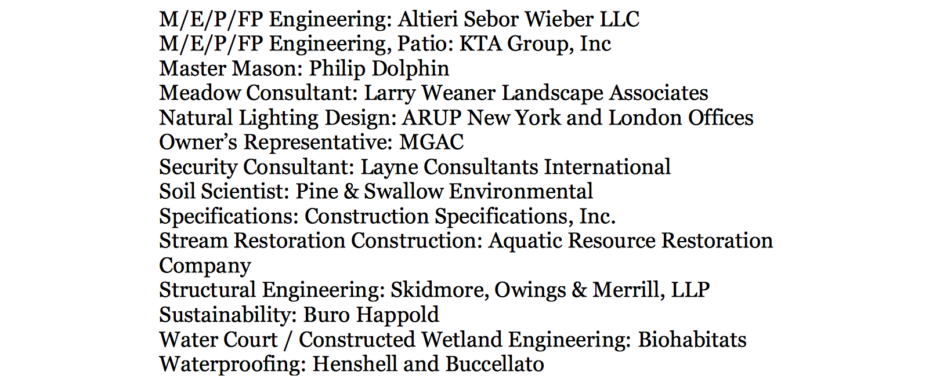

ARCHITECTURAL FACT SHEET: THE NEW GLENSTONE

Approach to the Pavilions. Photo: Iwan Baan. Courtesy: Glenstone Museum.

————————————-

Interview images courtesy of Thomas Phifer & Partners.

Interview transcribed / portfolio formatted by Jeff Heatley.

——————————-

Visit these AAQ Museum Architecture Portfolios (links)

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge / 2014

MAD — Museum of Arts and Design, NYC / 2016

Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY / 2012

The Clark Institute of Art, Berkshires / 2014

The Morgan Library & Museum, NYC / 2006

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford / 2017

Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC / 2015

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven / 2012

____________________________________________________________________________